Bioethics Forum Essay

Do You Want the Police Snooping in Your DNA?

In late April, a suspect thought to be the Golden State Killer, a man who had eluded police for decades after committing a string of murders and rapes in Northern California and Orange County between 1976 and 1986, was identified on the basis of DNA evidence. Although we celebrate the dogged pursuit of a more than 30-year-old cold case, the episode has drawn public attention to the evolving ways in which law enforcement is using genetic data to identify suspects—and to the consequent risks to the privacy of genetic data.

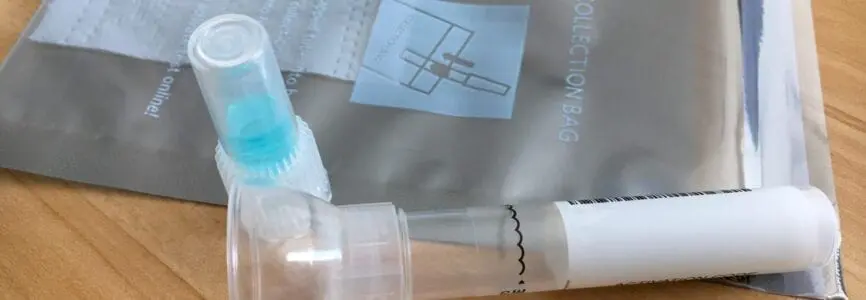

Using DNA recovered from one of the rape victims, law enforcement officers submitted genetic information from the unidentified killer to a publicly accessible genealogy website, under the pretense of trying to identify extended family members. With a list of people who were probably related to the suspect, they narrowed the group of suspects to a person of the right age and location to be the killer. That he turned out to have been a police officer was not a surprise to investigators, who had long been impressed by the killer’s careful actions to cover his trail.

The methods used to catch the suspect were clever, scientifically sound, and done with laudable intent: to protect the public from a man thought to be responsible for a dozen murders and at least 45 rapes. But the process used to match the DNA sample of the unknown suspect with his relatives took unfair advantage of people who had submitted DNA samples for a very different purpose. In doing so, it called into question the privacy of DNA data being collected for a wide range of purposes.

How can criminal suspects be traced with genetic evidence in a fairer and more transparent process? Services collecting DNA for purposes ranging from direct-to-consumer testing for predispositions to medical conditions to ancestry websites should obtain consent up front about the use of their data by law enforcement to identify dangerous criminals. We assume that many, perhaps most, people would consent to have their genetic data used for this purpose. But that should be a personal choice made on an informed basis.

Data-sharing policies should be simple, transparent, and understandable, highlighted or bulleted prominently in the conditions and terms to which persons submitting DNA samples or genetic data agree. Moreover, participants in these services should have the ability to opt out of granting access to law enforcement without having to forego the services they seek.

The actions of law enforcement in the Golden State Killer case—and the disclosures since then that other police departments are using similar approaches—could have unintended consequences. Aware that DNA data can be utilized without their knowledge, people may be understandably reluctant not just to take advantage of genealogy services, but also wary of donating DNA samples for even more socially useful purposes.

Clinical medicine is rapidly moving into the genomic era. Medical research increasingly depends on the aggregation of large amounts of genetic and other data to identify causes of disease and potential treatments. Although the matching services available to investigators in the Golden State case are not publicly available for DNA samples contributed for purposes of clinical diagnosis and research, many members of the public may not distinguish between these situations.

The impact may be particularly great for minority communities. Due to a lengthy record of past abuses, the African-American community in particular has expressed mistrust of scientists and physicians, and a consequent reluctance to participate in genetic research and genetic medicine. Underrepresentation of ethnic communities makes it difficult to differentiate normal genetic variants common in some ethnic groups from disease-causing genetic variants. This can lead to difficulty in interpreting genetic results in these communities and limits our ability to identify disease risks and appropriate preventive measures. Yet these are precisely the communities likely to be most suspicious of the consequences of potential law enforcement access to their data.

Large amounts of genomic data are now in the hands of companies performing genealogic services, recreational genetic testing, medical genetic analyses, and biomedical research. For the potential of these services to be realized, the public will need to be reassured that they have not and will not provide law enforcement access to their data without their consent. University-based genetic researchers already generally protect their data with certificates of confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health that preclude non-consensual access by law enforcement.

We are on the verge of significant advances in biomedical research and medical treatment using genetic data. Protecting the privacy of genetic information is critical to enable this progress to continue by ensuring public trust.

Wendy Chung, MD, PhD, is the Kennedy Family Professor of Pediatrics in Medicine at Columbia University Medical Center. Volkan Okur, MD, is a medical geneticist and postdoctoral research scientist in the Department of Pediatrics at Columbia. Paul S. Appelbaum, MD, is the Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, & Law; Director of the Center for Research on Ethical, Legal & Social Implications of Psychiatric, Neurologic & Behavioral Genetics at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons; and a Hastings Center Fellow.

45% of The Hastings Center’s work is supported by individual donors like you.

Support our work.

In 2018, police found the Golden State Killer through DNA from a “publicly accessible genealogy website.”[1] In “Do You Want the Police Snooping in Your DNA?,” Wendy Chung, Volkan Okur, and Paul Appelbaum write, “[T]he process used to match the DNA sample of the unknown suspect with his relatives took unfair advantage of people who had submitted DNA samples for a very different purpose. In doing so, it called into question the privacy of DNA data being collected for a wide range of purposes.”[1]

I have a few thoughts and questions.

On the website for 23andMe, the company writes, “Use of the 23andMe Personal Genetic Service for casework and other criminal investigations falls outside the scope of our services intended use.”[1] However, products and services are often used for things outside of their original intended purpose. Why should law enforcement not use data from publicly accessible websites? Should this data be limited to certain platforms? For example, law enforcement may find evidence for a crime on Instagram or Facebook.

On the website for 23andMe, the company assures individuals, “We will not release any individual-level personal information to law enforcement unless we are required to do so by court order, subpoena, search warrant or other requests that we determine are legally valid.”[2] This does not mean that the data is never accessible to law enforcement. 23andMe is saying that they will not freely provide the information to law enforcement, and, instead, authorities will have to go through the courts. While authorities must provide a court order, subpoena, or search warrant to access data from 23andMe, what is stopping them from signing up as a new user and submitting suspect DNA to find relatives? To participate in 23andMe, the user has to guarantee that any sample they submit is either their own or someone they received “legal authorization” from.[3] Will this really stop authorities? Who will discipline them? Most likely, the excitement and relief from finding a violent offender will overshadow the details. Also, law enforcement may be able to gather other evidence once they find out the criminal’s identity. But, the end does not justify the means.

The authorities in the Golden State Killer case submitted genetic information “under the pretense of trying to identify extended family members.”[1] While this is unethical and against the terms and conditions for 23andMe, how does using childrens’ DNA to find paternity factor into this, since children cannot legally consent?

Can “publicly accessible genealogy websites” be compared to social media? Even though our profiles may be set to ‘private,’ our data is still accessible by people with the right skills. Is anything really ever private?

In the United States, citizens give up certain rights in order to be protected from others. For example, a citizen has the right to own land, but they do not have the right to take land from another person. Does this extend to DNA? If a citizen willingly uploads their DNA to a “publicly accessible genealogy website,” can the government use this information to protect the public and help find violent criminals?

How does this compare to police digging through garbage to find something with a suspect’s DNA? Even if you don’t submit your DNA to a genealogy website, your DNA is still out there and accessible by law enforcement.

A lot of people submit their DNA to 23andMe not knowing what they will find. For example, my mom’s half-sister submitted her daughter’s DNA to find out more information about genetic diseases and ended up finding that she had a half-sister she never knew about. This caused a lot of turmoil in their family, uncovering deep secrets. By submitting DNA to 23andMe, crimes could be uncovered without law enforcement ever intervening. For example, if a woman has a child from being raped and the child does 23andMe, along with the rapist’s sister, then they will be connected. The woman and her child would be able to find the man that raped her. Certain pieces have to come together for this to happen, but it is very possible, especially as more and more people send in their DNA.

Even though we agree to terms and conditions before submitting DNA, I don’t think anything is considered wholly private this day in age. Do we accept some level of invasion in order to receive DNA-related information? Should consent extend to DNA relatives? You may choose not to participate, but participation from a close DNA relative will still affect you. After all, my mother’s birth-mom did not submit her DNA, and her life was still ravaged.

Notes

1. Wendy Chung, Volkan Okur, Paul Appelbaum, “Do You Want the Police Snooping in Your DNA?,” The Hastings Center, published June 15, 2018, https://www.thehastingscenter.org/want-police-snooping-dna/.

2. “Your privacy comes first.” 23andMe, https://www.23andme.com/privacy/#

3. “23andMe Guide for Law Enforcement,” 23andMe, https://www.23andme.com/law-enforcement-guide/#:~:text=Those%20who%20wish%20to%20participate,the%20TOS%20on%20their%20behalf.