Bioethics Forum Essay

Rationality as Understood by a Neanderthal

There is a theory, or the beginnings of a theory, that one of the distinguishing features of modern humans is a kind of irrationality. Obviously, we humans also possess impressive forms of rationality, what with our tool-making, our sciences, our languages, and all the story-telling and philosophizing and culture-building that languages make possible, but the theory is that something about our forms of rationality generates a kind of madness.

“We are crazy in some way,” Svante Pääbo, head of the evolutionary genetics department in the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, in Leipzig, told the New Yorker’s Elizabeth Kolbert in 2011. Consider the sea travel that took modern humans to nearly every island in the Pacific Ocean. “Part of that is technology, of course; you have to have ships to do it. But there is also, I like to think or say, some madness there. You know? How many people must have sailed out and vanished on the Pacific before you found Easter Island? I mean, it’s ridiculous. And why do you do that? Is it for the glory? For immortality? For curiosity? And now we go to Mars. We never stop.”

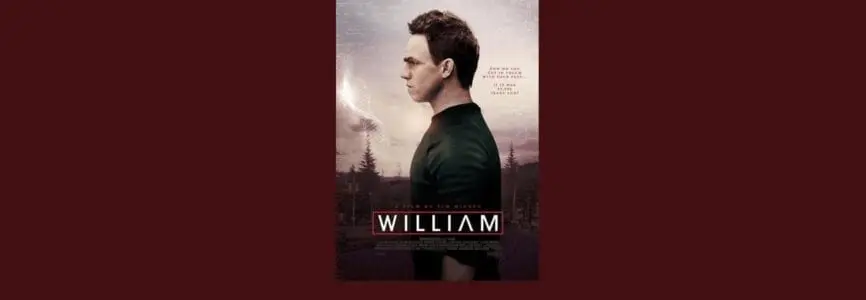

Such musings about human nature, about what it is that drove Homo sapiens clear around the globe—in the process replacing Neanderthals, Denisovans, “Hobbits,” and any ancient forms of humans and still slowly replacing most other large mammalian species—is at the heart of the low-budget but well-acted and artistically filmed indie movie William, which premiered in New York and Los Angeles on April 12 and explores the question, What would it be like if a Neanderthal were born and raised in a modern, industrialized society today?

The story begins with a science fiction premise: a couple of clever but crazy Homo sapiens, believing we modern humans have something to learn from our extinct cousins, manage to produce a Neanderthal fetus through cloning (involving DNA extracted from Neanderthal remains that a colleague has pulled out of a bog), and one of them has the fetus secretly implanted into her womb. But the rest of the movie is resolutely not science fiction, and anyone looking for an action and adventure will be disappointed. It’s a straightforward, self-consciously serious meditation on human nature—or really, human natures—and the relationship of human natures to the rest of nature.

The protagonist, as he grows up Neanderthal, is monstrously strong but gentle and deeply human. He is sensitive and thoughtful, apparently very intelligent, but also close to incapable of metaphoric thought, of using one thing to mentally represent another thing. “I think that takes us further from the truth,” he says. He craves human companionship, but because he lacks the special human craziness of seeing one thing as something else, he cannot connect with the kinds of stories that knit Homo sapiens into societies and propel them to Easter Island—religious stories, origin stories, even simple jokes that might draw a few friends together. He is immersed in the literal world. Although analytic, he seems to dislike abstract thought in general; would a proclivity to see things as falling into categories be another aspect of Homo sapiens’ craziness, from the point of view of Homo neanderthalensis?

The most beautiful scenes in the movie are shot in British Columbia and provide opportunities to think about the relationship of human natures to nature. William camps with friends by a pond, builds a campfire, hikes, and sings in the woods. He’s in tune with his body, enjoying his own immense physicality, and in tune with what’s around him. It’s out in nature that he feels a kind of belonging. There’s a sadness to his joy, though. When the camera zooms back to reveal a city skyline looming, encroaching, in the distance, we know what’s coming next.

Some reviewers, expecting the Neanderthal version of Jurassic Park, have found it slow. One pans it as a wooden morality tale about the evils of unrestrained science, and this criticism is not wholly off base. One of the clever, crazy H. sapiens is something of a caricature of the write-my-own-rules scientist, and a bit-part character flashes on the screen to say, “As a bioethicist, I find the idea abhorrent.” In a Q&A following the New York premier, the director, Tim Disney, made no bones about the fact that he thinks creating a Neanderthal would be wrong.

But the movie can also be enjoyed as a surprisingly gentle and sad personal drama, and for any philosophers or evolutionary geneticists in the audience, it makes for a plenty interesting hour and forty minutes. As the ability to alter and (maybe) recreate species gets more refined, it’s a worthwhile contribution to the public discussion about whether that’s a good thing to do. That discussion must start with the values questions, and one of the best ways to do that is to tell stories, even fictive stories, that get the brain’s moral machinery spinning. Perhaps we could learn something from bringing a Neanderthal into modern society; we also have something to learn from imagining that we already have.

Gregory E. Kaebnick is a research scholar at The Hastings Center and editor of the Hastings Center Report. He directs the Center’s Humans and Nature program area and co-edited a special report, Recreating the Wild: De-Extinction, Technology, and the Ethics of Conservation.

45% of The Hastings Center’s work is supported by individual donors like you. Support our work.

Very interesting piece; and it makes me want to watch the film.

But the premise of the article reminds me of something I think Stephen Hawking once said as he contemplated climate change and its consequences–the growing destruction of Earth by human inventions and attitudes. As I remember it, it was to the effect that…”it is not clear that rationality is an adaptive evolutionary trait…”

If the words are not exactly correct, I think the perception definitely is.

I think William, who rejects metaphoric thought because it takes us further from the truth, is a Platonist, or possibly on the autism spectrum. Deeply human in either case.