Bioethics Forum Essay

Do We Have a Moral Obligation to Genetically Enhance our Children?

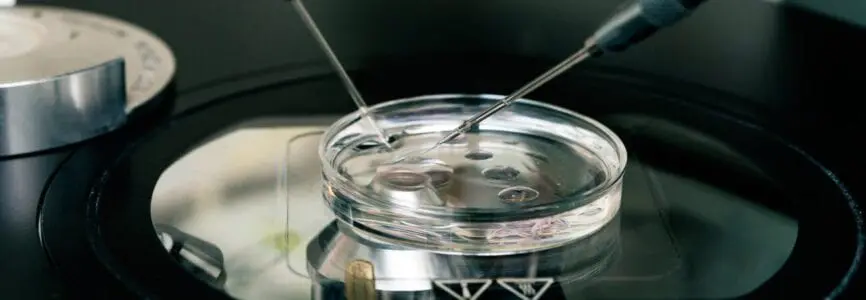

The Oxford philosopher Julian Savulescu, among others, has argued that prospective parents engaging in embryo selection using preimplantation genetic diagnosis not only may seek to have genetically enhanced children but are morally obligated do so. (See, for example, his essay “Procreative Beneficence: Why We Should Select the Best Children,” Bioethics, 15, no.5/6, 2001.)

I argue that Savulescu is wrong.

Savulescu defends a moral principle he calls the principle of procreative beneficence. He states that, under this principle, prospective parents choosing among embryos “should select the child, of the possible children they could have, who is expected to have the best life, or at least as good a life as the others, based on the relevant, available information.” Among the possible enhancements he identifies are intelligence, memory, self-discipline, impulse control, foresight, patience, and a sense of humor.

Savulescu has not yet extended this principle beyond preimplantation genetic diagnosis to gene editing. He acknowledges that gene editing currently carries health risks not associated with embryo selection, and that these risks outweigh any obligation to try to bring about “the best life” for a child.

But given the speed with which CRISPR technology is advancing, it seems that we are not far away from safe, effective gene enhancements for some traits. So according to Savulescu’s principle, when sufficient levels of safety are reached, all parents with the means to afford gene editing for enhancement will have a moral obligation to do so.

I will specify my criticisms of Savulescu’s principle, but first I want to say that I fully support the reproductive use of gene editing technology for the prevention and elimination of serious genetic diseases.

If we could use gene editing to remove the gene sequences in an embryo that cause sickle cell disease or cystic fibrosis, I would say not only that we may do so, but in the case of such severe diseases, that we have a moral obligation to do so.

I think that parents and medical professionals should always try to give a child a healthy start in life. This principle underlies the very firm moral intuition that pregnant women should not take drugs or drink alcohol to excess during pregnancy. In an era of safe gene editing, I believe it would extend to the obligation to use this technology to avoid transmitting grave inherited disease conditions.

Unlike Savulescu, however, I don’t see parents’ obligation extending to genetic interventions that go beyond preventing disease and making people “better than well.” These include cosmetic enhancements, muscle enhancements increasing athletic performance, or cognitive enhancements such as high IQ or improved learning ability.

There are three reasons I reject the principle of procreative beneficence.

First, all genetic manipulations carry some risks, whether of immediate off-target gene insertions or more complex maladies, as when the pursuit of improved learning ability may bring with it a greater sensitivity to pain (an association found in some animal studies). While it is always reasonable in medicine to incur risks to treat or prevent diseases, it is by no means clear that it is wise to do so with medically unnecessary enhancements. This is especially true when children are involved. How would we feel about parents who put their daughter through risky plastic surgeries to improve her performance in beauty contests? In other words, no matter how low the risks of enhancements, they lack the clear justification of disease treatment or prevention. The fact that genetic manipulation of early embryos or gametes affects the germ line, potentially creating new heritable diseases, compounds the problem.

Second, while I believe that parents have a stern obligation to try to prevent harm to their child, it is not clear to me that they have an obligation to provide that child “the best life.” Such an obligation is what moral theorists call “supererogatory.” It involves actions above and beyond the call of duty, but which, by their very nature are not morally obligatory. I suppose there are myriad ways that you or I could make our children’s lives better—for example, we could put all our money into paying for the very best private schools—but I don’t think we are morally obligated to pursue these, any more than we are obligated to intervene genetically to give our kids the best physical constitutions. As a moral philosopher, I might add that I think that Savulescu’s insistence on this obligation follows from his continuing reliance, despite denials, on a form of on utilitarianism with its maximization of happiness. So there is a deep theoretical problem at work here.

Third, I reject Savulescu’s procreative beneficence principle because I reject its assumption that we can identify nondisease-related traits that clearly make one’s life better. Among people with a normal IQ, good memory, numeracy, and literacy are useful for a successful life, but it is by no means clear that enhancing any one of these values to a supernormal level would result in a child having a better life. The interaction of gene traits with one another and with the environment is too complex to allow the kind of predictive confidence about any trait that would be needed to apply Savulescu’s principle.

Let me illustrate this complexity with a story. In college, I had two roommates. (For privacy’s sake I’m changing their names.) John graduated cum laude, went on to a fine Ivy League law school, and reached the apogee of his career when he was elected mayor of his small hometown. I was the best student of the three, graduating summa cum laude and having a solid and satisfying career as an academic ethicist. Harry, was by far the poorest student among us: he barely applied himself, earned straight C’s, and couldn’t get into a top law school. As a result, Harry moved into an arcane field of law at a lesser New York firm, and eventually rose to the top of the new field of merger and acquisition law. Today, Harry is an extremely wealthy financial industry attorney, and has served as trustee of Brown University, our alma mater.

I am not telling this story to argue that money is the measure of the man. Nor am I saying that any of the traits that led my roommates and me into our lives are genetically based. I offer this anecdote only to indicate how difficult—if not impossible—it is to predict that any character trait, genetic or otherwise, will lead to worldly success much less to happiness. This means that, above and beyond striving to help their offspring have normal health, parents are under no obligation to use genetic technologies to provide those children with nondisease-related genetic enhancements.

If parents are under no obligation to use gene editing for enhancement purposes, may they ethically do so? Should parents be allowed to pursue such genetic enhancements, at least when they’re shown to be sufficiently safe?

This is a complex question that I have written a book about (Babies by Design, 2007). There are many reasons people fear the use of genetics for nondisease-related enhancements. One fear is that money and genes will work together to produce a “genobility,” a society marked by genetically increased social inequalities. This could happen on a national or international basis. Another is the fear that, in the quest to have athletically gifted children, parents will spark an “arms race,” seeking positional advantage for their children, that concludes by advantaging no one and maybe even harming them. An analogy here is to sports doping which, if widely pursued, benefits no one and risks damaging the individual athletes.

I have no easy answer to the question of whether these ethical concerns or others are so significant that we should try to prohibit parents from these choices.

But I do know that parents seeking such enhancements will likely be disappointed. As I said, parents are under no obligation to pursue genetic enhancements. Furthermore, it’s probably foolish to try to secure the best life possible for one’s child by genetic means. We cannot identify what makes for a best life in this connection. The healthy natural human genome has enough variety in it to let any child successfully navigate the world and fulfill his or her own vision of happiness.

Ronald M. Green is professor emeritus of religion and ethics at Dartmouth College. This essay is a version of a talk he gave at a preconference workshop on genetics organized by The Hastings Center at the World Conference of Science Journalists on October 26.