Bioethics Forum Essay

What 23andMe Owes its Users

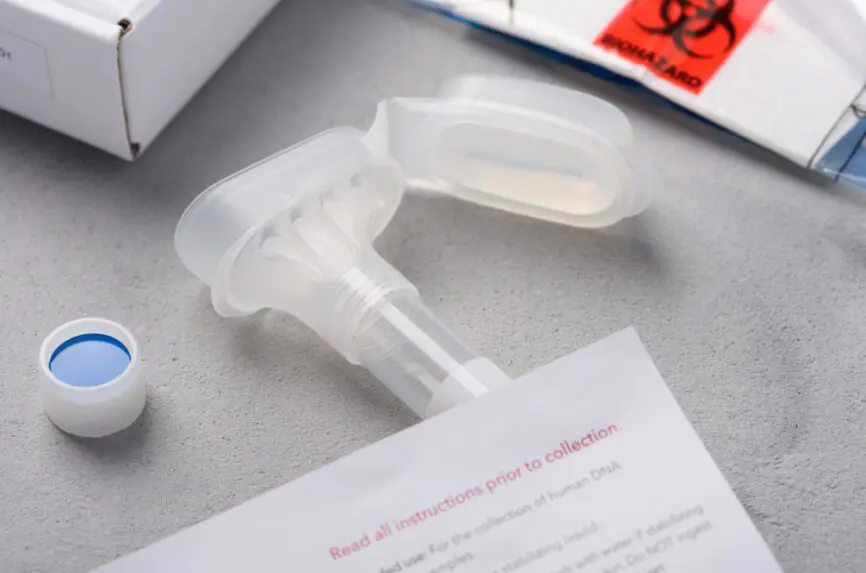

Remember September 2008? Your investment in Lehman Brothers common stock is going strong and you find your way to a – what? A spit party? It’s one of the inaugural events for a West Coast startup: 23andMe. With the hope of learning something fun, or to be networked with genotypically similar people, you spit into a test tube. A few weeks later you learn that your family is roughly where you thought they were from and that your eyes are indeed brown.

September 2024: Lehman is a punchline in HBO’s Industry, and while half watching the show you see a push notification: the 23andMe board has resigned. That night, you can’t sleep. You don’t mind that Insta and TikTok collect your scrolling habits; at least you get a dopamine rush in exchange. But your genome feels different. In the intervening years, 23andMe has sent you new findings related to your health status. You wonder: Is my data protected? Can I get it back?

There are protections for users of 23andMe and other direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies. Federal laws, including the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) and the Affordable Care Act, protect users from employment and insurance discrimination. Residents of certain states including California have agencies where they can register complaints. 23andMe, which is based in California, has a policy in line with California citizens’ new right to access and delete their data. European residents have even more extensive rights over their digital data.

American users can rest assured that there are strong legal mechanisms under the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. that can block foreign acquisition of U.S. firms on national security grounds. For certain critical sectors like biotech, the committee may consider, among other factors, whether a proposed transaction would result in the U.S. losing its place as a global industry leader as part of its review.

Any attempt by a foreign company to acquire 23andMe would be subject to a CFIUS review and could be blocked on national security grounds, particularly if the foreign company is headquartered in a “country of special concern” such as China, Russia, or Iran. As for acquisitions by U.S. companies, the legal landscape is a bit more Wild West. Buyers based in the U.S. could change policies to which users agreed long ago, in a world rather different than ours.

November 2024: With a new board the immediate crisis at 23andMe has been averted. However, long-term concerns remain regarding potential buyers and how they might respond to 23andMe’s layoffs and shuttering of its drug development arm, both of which suggest instability of the company. 23andMe and other DTC genetic testing companies should consider what they owe their users.

One thing they owe users is to implement a policy that, in the case of a sale, the companies will notify users multiple times and in multiple ways and give them the option of deleting their data. These notifications should go out after the sale has been approved but before ownership changes. Given the vast benefit that DTC genetics companies derive from user samples, and the arguably small benefit that users derive from their services relative to the risks, this is a reasonable concession. Such action would also align with present movement towards ease of cancellation of subscriptions.

One can imagine several contacts via email or phone/text, and a standing, highly visible message on the company’s website. Each notification would share information on the buyer and be designed to help users determine whether they want their data to remain with the new company. Another option could be a sale clause that prevents the buyer from changing the terms and conditions without multiple instances of alerting users and offering easy opt out via deletion of data.

But can you get your genome data back? Not exactly. You can ask 23andMe to delete it. This prevents future buyers from having your data. If the company policy changes and you are in or move to a jurisdiction such as California or Europe, you will likely retain the right to delete your data, regardless of any new corporate policies. Otherwise, you could lose the right to delete your data.

If you are among the over 80% of users who opted in to have your genomics data used for research, your data may be part of a large science project. There is no “unspitting” in this case. It should be a solace, though, that your data is probably combined with so many other people’s data it would be difficult, laborious, and complicated – if not impossible — to distinguish yours from theirs.

If you feel queasy about the corporate situation but do not want to deprive researchers of your participation in science, there may be a middle path. You can request the raw data from your spit tube and offer it to a university of your choice that is doing genetic research. Or better yet, perhaps the National Institutes of Health would consider collaborating with 23andMe and similar companies to back up all their data, protect it, and restrict its use to nonprofit or academic research labs. This would protect the users and the societal benefit derived from their data.

Jonathan LoTempio, Jr., PhD, is a bioethics fellow at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine trained in bioinformatics and bioethics. LinkedIn/Jonathan lotempio.