Bioethics Forum Essay

The Overlooked Father of Modern Research Protections

Thirty years gone, but the spirit of Richard Nixon still rattles around in my head like Marley’s ghost. Instead of ledgers and cash boxes, he carries an Enemies List. “Never forget, the press is the enemy. The establishment is the enemy. The professors are the enemy. Professors are the enemy. Write that on a blackboard 100 times and never forget it,” Nixon told Henry Kissinger in 1972. I check at least two of those three boxes, but I doubt I would qualify for Nixon’s list anymore. The more time passes, the more Nixon looks like a strange, unlikely political ally.

For American liberals of a certain age, especially those disillusioned with the current state of politics, it has become common to look back in astonishment on the progressive domestic measures that Nixon signed into law. The same man whom Hunter S. Thompson called “a political monster straight out of Grendel” signed the Clean Air and Water Acts, the Equal Employment Opportunity Act, the Endangered Species Act, and measures establishing the Environmental Protection Agency and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration. But the progressive measure overlooked even by Nixon enthusiasts is the National Research Act, which Nixon signed on July 12, 1974, and which gave us our modern research protection system.

If there were an origin story for the National Research Act, it would probably begin in early 1972. In January, Mike Wilkins, a young internist, appeared on an ABC news report exposing the horrific conditions at the Willowbrook State School in Staten Island, where institutionalized, intellectually disabled children had been intentionally infected with hepatitis A and B. Shortly afterwards, Martha Stephens, an English professor at the University of Cincinnati, organized a press conference protesting Pentagon-funded studies in which vulnerable cancer patients were given whole-body irradiation to test how much radiation a soldier could withstand in a nuclear attack. But the most explosive report came in July, when documents provided to the Associated Press by whistleblower Peter Buxtun exposed the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, a study by the U.S. Public Health Service in which poor, Black men in Alabama with syphilis were deceived and deprived of treatment for 40 years.

Whether Nixon was shocked by the scandals is hard to say. He certainly had no sympathy for whistleblowers. His covert Special Investigations Unit, aka “the plumbers,” was devised to prevent internal leaks and punish violators. Nixon was also preoccupied with his re-election campaign. On June 17, 1972, just over a month before the Tuskegee story broke, Washington police arrested five men sent by the plumbers to break into Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate Hotel. By February 1973, when Democratic Senator Edward Kennedy introduced legislation to establish the Senate Watergate Committee, Nixon was waist-deep in a scandal of his own.

It is Edward Kennedy who deserves most of the credit for the subsequent research reforms. As chair of a Senate subcommittee on health, Kennedy had been holding hearings on a range of medical abuses when the Tuskegee story broke. In November 1972, he called for the establishment of federal policy on use of human subjects in medical experimentation, charging that medical researchers were exploiting the poor and uneducated. He began hearings on the Tuskegee study in February and March 1973. Yet the Watergate scandal continued to intrude. When Peter Buxtun, the Tuskegee whistleblower, was giving his Senate testimony, he was interrupted by two men rushing into the room. “I’m feeling kind of stupid. I’m halfway through a sentence,” Buxtun told me when I interviewed him several years ago. When Buxtun returned to his seat, the woman sitting next to him leaned over and whispered, “Haldeman, Ehrlichman and Dean have resigned.”

When the Tuskegee hearings were over, Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota introduced a bill to create a National Human Experimentation Board. Humphrey had in mind a powerful, centralized board of experts, appointed by the president, with the authority to regulate and review all federally funded medical research. A powerful board seemed like the best way to protect vulnerable people from being exploited by a medical establishment that viewed them as useful “research material.” But the medical establishment vigorously opposed any effort at regulation and Humphrey’s bill failed.

In light of that failure, Kennedy introduced a bill that would become the National Research Act. Although it is often portrayed as a landmark reform, the National Research Act was actually a watered-down political compromise. It established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research–a temporary body with purely advisory power–and delegated the oversight of medical research to local peer-review committees (IRBs) of the sort already in existence. It also endorsed a patchwork of federal guidelines governing research that has come to be known as the Common Rule. Yet as depleted as the National Research Act was, it still marked a significant improvement on the status quo.

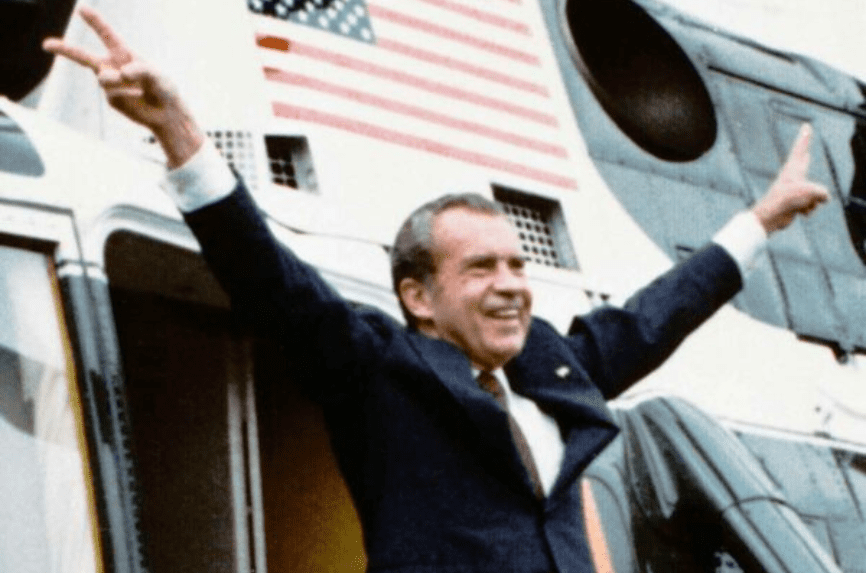

As far as I can tell, there is no written record of Nixon’s opinion on the National Research Act. On July 12, 1974, the day Nixon signed it into law, newspaper headlines were dominated yet again by Watergate. The House Judiciary Committee had just released 3,888 pages of damning evidence of the Nixon White House’s abuses of power. Later that day, John Ehrlichman, a top Nixon aide, was found guilty of four criminal charges. According to Woodward and Bernstein’s The Final Days, Nixon boarded Air Force One at 4 pm that day to take refuge at his private estate in San Clemente. It would be just over three weeks before he resigned in disgrace.

The evidence suggests that when Nixon signed the National Research Act into law, he had other pressing matters on his mind. In fact, it is entirely possible that he gave it no thought at all. Yet it is not impossible that he endorsed the act. Nixon was nothing if not complicated: a shy, socially inept man who chose a life in the public eye; a rabid anti-communist who established diplomatic relations with China; a conservative who expressed racist views in private yet desegregated more Southern schools than any other president. I would like to imagine that he approved.

Carl Elliott, MD, PhD, is a professor in the department of philosophy at the University of Minnesota and a Hastings Center fellow. His new book, The Occasional Human Sacrifice: Medical Experimentation and the Price of Saying No, will be published in May. @FearLoathingBTX

While Nixon may be credited with advances viewed as progressive in light of the current political climate, it is important not to conflate causality with presidential disinterest. This distinction emerges in a marvelous little book, “The President and the Professor: Daniel Patrick Moynihan in the Nixon White House” by Stephen Hess of the Brookings Institute. Hess profiles the relationship between Nixon and Moynihan who served as the domestic policy advisor. It was a paradoxical relationship because Moynihan was a quintessential liberal from Cambridge and on the opposite end of the political spectrum. Hess writes that Moynihan provided Nixon with a modicum of legitimacy with intellectual elites who shunned the president. But more importantly, for Professor Elliott’s thesis, is that Nixon delegated domestic policy to Moynihan. The president’s overwhelming focus was foreign policy, tensions with the Soviet Union, normalization of relations with China, and the war in Vietnam. While Moynihan left the administration in 1970 and later was appointed Ambassador to India, presidential priorities remained focused on international affairs at the expense of domestic policy until Watergate threatened the administration. Given these priorities casting Nixon as the “overlooked father of modern research protections” is misplaced praise and a distortion of the historical record. As Professor Elliott notes, and Al Jonsen recounts in his “Birth of Bioethics,” others like Senator Kennedy were more responsible for research protections than Nixon.

As E.B. White may have once said, “Explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better but the frog dies in the process.”