Bioethics Forum Essay

A Right to Seek Payment for One’s Tissue

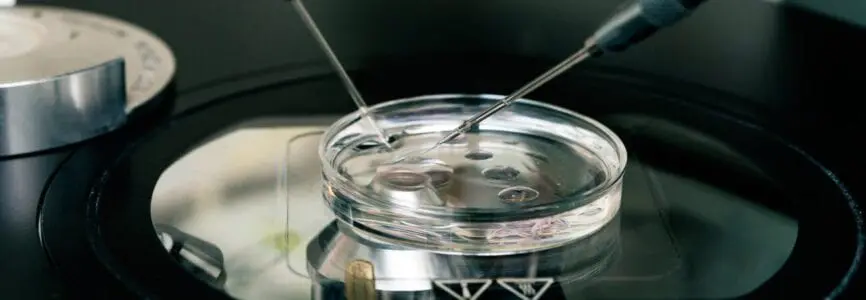

After much anticipation, on April 22, HBO debuted The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, a film based on Rebecca Skloot’s bestselling book, starring Oprah Winfrey. Lacks’s cells provided the foundation for the now infamous HeLa cell line, the first set of human cells able to reproduce outside the body. So-called immortal cell lines like HeLa are immensely valuable for biomedical science, as they allow researchers to experiment on human cells without experimenting on humans. Researchers and institutions have used her cells to achieve significant scientific discoveries and develop vaccines and treatments, and as a result they have reaped considerable profits.

What makes these HeLa cells infamous is their provenance: in 1951, researchers at Johns Hopkins harvested cancerous cells from Henrietta’s cervix—without her knowledge or consent. The timing of the film is particularly apt, given that one of Henrietta’s family members recently made headlines for announcing his intent to sue Johns Hopkins for failing to compensate her. Henrietta’s oldest son and executor of her estate explained that although “[his] mother would be so proud that her cells saved lives . . . she’d be horrified that Johns Hopkins profited while her family to this day has no rights.”

Henrietta Lacks’s story is so moving because of its universality: something similar could have happened – and potentially still could happen – to any of us. And her story, including the pending lawsuit, raises the important question, what rights do patients and research subjects have regarding the use of their tissue? In the last decade, participants have demanded increased consent rights, including the rights to be paid for their participation, to be compensated for the harms that occur due to their participation, and even to direct the course of research. Of these emerging rights, none have garnered more attention than the right of participants to seek compensation for research utilizing their tissue or other biological samples.

Allowing compensation could empower research subjects by making them more active participants, it could create buy-in and increase the willingness to participate in research, and it could help to avoid potential feelings of exploitation. Despite these advantages, neither the rules governing human research nor legal precedent support research participants’ having any legal interests in their excised cells.

Interestingly enough, the Department of Health and Human Services and other federal agencies could have ended this controversy earlier this year. Regulations known as the Common Rule govern federally funded human subject research. Originally drafted in 1981 and revised in 1991, the Common Rule was intended to ensure that researchers obtain and document voluntary informed consent by research participants. Despite this lofty goal, it provided little or no protection for individuals whose tissue was used for research. In fact, it was commonly accepted that most research on excised tissue was not even “human subjects research” to begin with. The Common Rule remained untouched for over two decades, despite the changing nature of biomedical research and stories such as Henrietta Lacks’s. Finally, in 2011, federal agencies began the lengthy process of updating the Common Rule, an effort that resulted in multiple iterations of the rule and thousands of public comments. The almost-six-year process culminated in a final rule, issued on President Barack Obama’s last day in office.

HHS’s comments accompanying the Final Rule acknowledged that “some who felt there is an entitlement to financially profit from discoveries described biospecimens as personal property,” similar to one’s property interest in “land, a house, or an arm.” Although HHS had the opportunity to explicitly provide a path for people to assert rights over their biospecimens, and—in particular, to negotiate the right to share in the profits of research–in its final Common Rule, it declined to do so.

At the most, the revised rule gestures toward an individual’s interest in knowing whether a researcher intends to profit from the research; in essence, this new requirement might, at the least, inform research participants that their tissue could have commercial value. Yet the failure to acknowledge any rights in one’s excised tissues leaves individuals with little recourse. How then can we protect the rights and interests of individuals who donate or have tissues taken during treatment or research? In other words, if the right to seek–or at least negotiate– compensation for having one’s tissue used in research is something we care about, we need to explore other avenues to ensuring this right.

One alternative, suggested by the public comment to the revised Common Rule, is to treat tissues as a commodity, and to allow individuals to negotiate their participation in research in return for compensation or a piece of the profits. However, legally, most courts have refused to view an informed consent document as a contract between researchers and participants. People seeking to create and to enforce commercial interests in their tissues may then have to go outside the traditional informed consent agreement and draft a separate, legally enforceable contract.

Alternatively, participants could attempt to sue investigators after the fact for using their tissue without allowing them to share in the profits of the research. However, in the few cases where research participants have attempted to control the fate of their tissue or seek to share in the profits of the research, courts have been reluctant to find such a right.

Regardless of the legal paradigm, we are in desperate need of an effective system for allowing research participants–at least ex ante–to seek to be compensated for their tissues. The Common Rule fails to achieve its goals of protecting autonomy and generating public trust by failing to recognize a right to commercialize tissue. While it may well be too late for the Lacks family to benefit from Henrietta’s contribution to science, we should ensure that future research participants are not denied that same opportunity.

Valerie Gutmann Koch is a visiting fellow at DePaul University College of Law and Director of Law and Ethics at the University of Chicago’s MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics. Follow her on Twitter at @vgkoch. Jessica L. Roberts is the George Butler Research Professor and Director of the Health Law & Policy Institute at the University of Houston Law Center. Follow her on Twitter at @jrobertsuhlc.