Bioethics Forum Essay

Bioethicists Should Speak Up Against Facilitated Communication

Last month, Netflix premiered the documentary Tell Them You Love Me, the story of former Rutgers University professor Anna Stubblefield, who was convicted of first-degree aggravated sexual assault in 2015 for raping Derrick Johnson, a profoundly intellectually disabled 28-year-old whose “consent” she claimed to have procured through facilitated communication. Tell Them You Love Me shot to the top of Netflix’s global streaming chart, and the response on social media was consistent: users found the film “disturbing”; they appropriately described Stubblefield as “delusional” and as a “predator”.

But few seemed aware that this thoroughly discredited intervention, in which a nonverbal and severely cognitively impaired person is assisted in spelling out messages on a letter board or keyboard through physical support provided by a non-disabled facilitator, is not only surging in popularity under different names–including the Rapid Prompting Method (RPM) and Spelling to Communicate (S2C)–but is also currently being platformed at the highest levels of science and education. In 2021, a letterboard user was appointed to the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee; in 2022, facilitated students graduated from UCLA, Berkeley, and Rollins College. And in 2023, a speller was featured in a webinar hosted by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

We’re concerned by the muted response of bioethicists to more than three decades of abusive and exploitative pseudoscience. A quick search reveals relatively little bioethics scholarship on this disreputable practice. Public discussions of FC in bioethics have included a panel of FC critics hosted at Harvard’s Petrie-Flom Center in 2016. And a 2020 Hastings Center event included prominent letter board user DJ Savarese. More broadly, FC raises the question of how the discipline should respond to consequential, even dangerous, health interventions that are widely embraced either in the absence of scientific evidence, or–-as in the case of FC-–despite overwhelming evidence that they just don’t work.

As a field, bioethics has an explicit obligation to defend vulnerable populations from abuse and exploitation. This basic maxim was essentially built into the discipline, embodied in the principle of Respect for Persons and clearly articulated in 1978 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in both the Belmont Report and in the statement on Research Involving Those Institutionalized as Mentally Infirm. Although Tom Beauchamp and James Childress re-branded this principle a year later in their classic textbook, Respect for Autonomy is just one of the “two separate moral requirements” required by the National Commission. Equally important as the maximization of the autonomy of capacitated individuals, although much less celebrated, is “the requirement to protect those with diminished autonomy,” which may require “extensive protection.” The degree of protection, according to the Report, should be calculated based “upon the risk of harm and the likelihood of benefit.”

FC spectacularly fails both sides of this cost-benefit analysis. Dozens of controlled studies dating back to the mid-1990s overwhelmingly prove that facilitators (often unintentionally) direct the output in FC through a host of cues, psychological biases, and ideomotor effects–the same small, unconscious movements that also explain Ouija boards and other allegedly paranormal phenomena (see Lilienfeld and Marshall, et al., 2015; Schlosser, Balandin and Hemsley et al., 2014; Hemsley, Bryant, and Schlosser et al., 2018). Following the publication of these studies, the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, the American Psychological Association, as well as many other organizations, issued position statements against FC. To this day, independent communication through facilitation has never been demonstrated under controlled conditions, even though the James Randi Education Foundation offered a $1 million prize for anyone who could successfully do so.

Not only is the evidence against FC unequivocal, but this intervention subjects severely cognitively impaired individuals to well-documented harms–the sexual abuse documented in the Stubblefield case representing only the most well-known example. More than five dozen false abuse claims were also made through FC, resulting in the imprisonment of parents and the placement of severely autistic children in foster care. There are significant opportunity and financial costs to this intervention as well, which not only costs upwards of $30,000 per year per student, but is pursued in place of evidence-based forms of alternative and augmentative communication (AAC). Most importantly and most routinely, every FC interaction involves the co-option of authentic autistic communication by nondisabled facilitators, which strips very disabled people of what little control they have over their day-to-day lives.

We understand why it is tempting to avoid this debate–in an era that privileges lived experience, those who challenge the authenticity of the sophisticated and poignant reflections that emerge through FC are often attacked as “ableist” perpetrators of “epistemological violence” . But there is too much at stake to be intimidated. In a 2012 paper critical of FC, James Todd rightly articulates a “moral obligation to be empirical,” which comprises three duties:

(a) Know exactly what we are doing (not just what we think we are doing),

(b) clearly and objectively determine whether our procedures are actually

bringing socially significant and objectively measurable (not imagined) benefits

to our clients, and (c) stop what we are doing if we cannot meet the standards

of a and b.

Although Todd is a psychologist, his attribution of these duties to those professions that “dabble as professionals in the lives of others, or teach other people to do so” certainly applies to bioethicists as well. And the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities recognizes this duty, requiring in its disclosure form that “all scientific research referred to, reported or used . . . will conform to the generally accepted standards of experimental design, data collection and analysis.” In short, it’s hardly a controversial claim that we who work in bioethics and the medical humanities should be guided by scientific fact and publicly reject pseudoscience, no matter how hopeful or affirming. Which means it’s well past time to mount a vigorous opposition to FC–before more nonverbal persons are hurt and more desperate parents fall prey to the charlatans who promise to channel their child’s intact mind, but who deliver nothing more than ventriloquism.

Amy S.F. Lutz, PhD, is a senior lecturer in the History and Sociology of Science Department at the University of Pennsylvania. @AmySFLutz

Dominic Sisti, PhD, is an associate professor of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and a Hastings Center fellow. https://www.linkedin.com/in/dominicsisti/

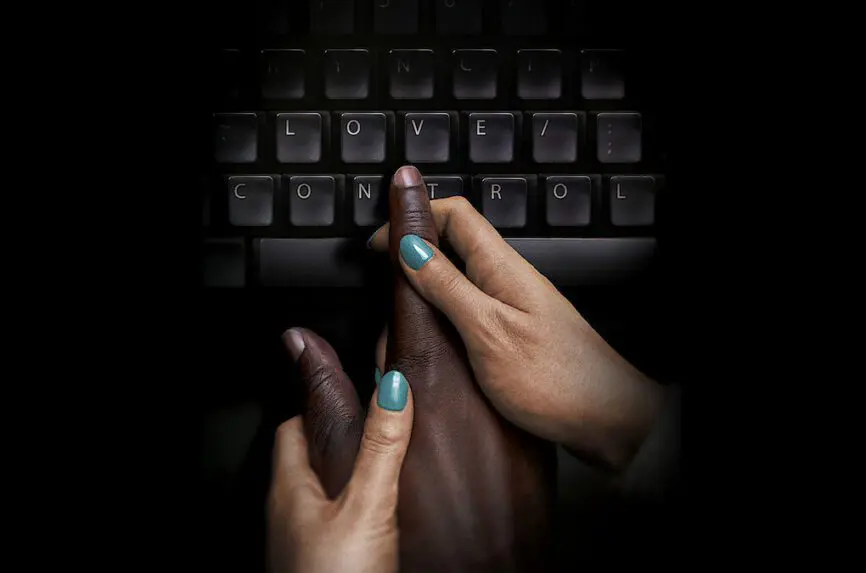

[Photo: Netflix]

These authors seek to make the case that bioethicists are duty bound to speak up against Facilitated Communication. They claim, “it’s hardly a controversial claim that we who work in bioethics and the medical humanities should be guided by scientific fact and publicly reject pseudoscience, no matter how hopeful or affirming.”

I would argue that these so-called “Experts” that opt to blazingly interfere in the lives of nonverbal individuals to challenge their chosen method of communication and or in this instance criticize Bioethicists under a banner of science have the utmost obligation to substantiate the accuracy of all their claims.

In this instance, the authors express dissatisfaction with the fact that bioethics scholarship has failed to mount a vigorous opposition to FC (which they have improperly defined to include RPM and S2C) which they deem an abusive and exploitative pseudoscience and then go as far to contend that Bioethicists have an actual duty to do so.

The authors claim that the alleged duty of the Bioethicist is predicated based upon two theories:

First, they claim that this mandate is embodied in the principles of Respect for Persons and clearly articulated in 1978 by the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research in the Belmont Report. A quick read of the 1978 Belmont Report reveals that it represents a government policy statement that is intended to protect humans which are subjects of biomedical and behavioral research. Hence, I would argue that the Belmont Report does NOT serve to create a duty which compels bioethicists to amount vigorous opposition to all forms of alleged Pseudoscience in clinical care including FC. A clinical decision to use FC as a mode of communication does NOT represent an instance where nonverbal humans are being subjected to biomedical and behavioral research. The distinction between research and practice must not be blurred.

Next the authors argue that Bioethicist have a general moral obligation to be empirical. In fact, they claim that the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities expressly recognizes this duty, by requiring in its disclosure form that “all scientific research referred to, reported or used … will confirm to the generally accepted standards of experimental design, data collection and analysis.” In reading this language, I see a duty that expressly focuses on guidelines and procedures for conducting biomedical research and NOT obligations compelling Bioethicist to oppose all forms of alleged pseudoscience that may affect human beings in clinical settings and all over the globe.

As a proud parent of a minimally verbal son with autism, I remain hopeful that the day will come when all communication science experts recognize the limitations of their knowledge and refrain from criticizing individuals that have selected a mode of communication that they fail to support. Instead, of seeking to criticize and shame professionals to support and adopt their preferred method of communication, these so called “experts” would be well advised to adopt a needed cross disciplinary approach to communication science research that can effectively address the many research gaps that exist with genuine wisdom free of bias and speculation.

– Anthony Tucci, LLM, ESQ, CPA

We appreciate your comment, but there are inaccuracies we feel obliged to correct.

First, you state that we “improperly defined [FC] to include RPM and S2C.” Importantly, only the RPM and S2C communities believe that these interventions are not forms of FC. Mainstream psychologists and speech-language pathologists consider RPM and S2C forms of FC because physical support from a facilitator is necessary for communication to occur; the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) issued a warning against both interventions precisely because they are FC variants (https://www.asha.org/slp/asha-warns-against-rapid-prompting-method-or-spelling-to-communicate/).

Second, you reference research “gaps” that suggest the evidence against FC is inconclusive. But forty controlled studies over five decades have overwhelmingly demonstrated that the facilitator is actually directing the output in FC, not the disabled person (for a summary of these papers, see https://www.facilitatedcommunication.org/controlled-studies). In contrast, there is not one controlled study that shows authentic communication with any form of FC. So when you reference “individuals that have selected a mode of communication that [experts] fail to support, it is exceedingly unlikely that the disabled people subjected to FC have made this choice. In fact, both RPM and S2C direct facilitators to ignore what is actually communicated by disabled users – through either speech (yes, some facilitated spellers actually have limited speech) or behavior – in favor of what is spelled with the facilitator. In short, FC practitioners are the ones who are guilty of disregarding the communication preferences of disabled people.

Finally, to the substantive point of your comment: that bioethicists do not have a duty to oppose pseudoscience because their obligations are confined exclusively to the ethics of human subject research. It’s true that bioethics emerged as a field largely (but not exclusively) in response to grossly unethical studies, such as those at Tuskegee and Willowbrook. But bioethicists quickly outgrew this initial focus and now intervene across a wide range of topics. Because pseudoscience raises important questions about consent, capacity, and harm, it has proven attractive to bioethicists – who have argued, amongst other things, against the use of stem cell research (McMahon and Thorsteinsdóttir 2010), homeopathy (Smith 2011), and pediatric chiropractic care (Homola 2016). And we agree with McMahon and Thorsteinsdóttir, who conclude that bioethicists should “speak out against therapies incorrectly presented as medically beneficial or scientifically based.”

Please recognize that my comments questioned the authority that you cited for the proposition that “Bioethicist” have an actual duty to speak out against pseudoscience. Lawyers must establish that the authority that we cite to support an argument is appropriate and of ongoing precedential value. These ethical mandates protect the integrity of justice and the rule of law. I assume that the field of bioethics has similar professional mandates. In your case, you have not satisfied this threshold. Your reply did not address these shortcomings, instead cites alternative sources.

Ironically, this essay has brought to light a more appropriate topic for the expertise of Bioethicist. The concept I am proposing for exploration involves a consideration of the ethical values at stake when individual communication rights come into conflict with the recommendations of speech and language professional trade associations. This topic is an extension of the topic public health and bioethics addressed by the Hasting Center Project on Ethics and Public Health. I am currently exploring conducting a similar research analysis on the intersection of science and the human rights of individuals with disabilities.

– Anthony Tucci, LLM, ESQ, CPA

I just read this article and the two comments. At age 77 with serious health issues since turning 70, although I have followed Facilitated Communication for 34 years, I am no longer able to quickly write the detailed comment I used to be able to do. However, much of the possible content of such a comment can be found on my website at https://groups.io/g/AutismFC. I would suggest reading one statement I wrote in 2011 found at https://groups.io/g/AutismFC/message/75

FC (Facilitated Communication) & the most basic human right of LIFE (7 June 2011)

Thanks to each and all for contributing to discussion of these issues, that go beyond FC, and touch on how we care for/care with profoundly impaired persons who struggle to communicate about themselves, their experiences, and their desires.

For two years I as an assisting Power of Attorney for my mother’s sister in a vegetative state. In the rural area of my aunt services and caregivers – of any sort – are challenging to find and keep; so we were beyond glad that a distant cousin welcomed Aunt Ruth into her privately owned adult home convenient for my mother to visit. When I visited Aunt Ruth and held her hand asking her questions was the small squeeze a response? was that slight turn of her head a communication? Mother through Ruth was communicating. I was not sure. Our cousin – who had the greatest extent and variety of effort with Ruth (who needed total care for all ADLs) – reported that Ruth expressed differentially, as if to communicate ‘that tastes good, I like that’ or ‘that hurts’.

Was our cousin transferring her thoughts or impressions onto Ruth? Importantly, for me to consider that question – that is also central to the story in the Netflix show and similar situations – I must explain that we TRUSTED our Cousin. Mother knew her well and knew her family. Mother knew others who had moved into Cousin’s home and knew their families. It seemed un-likely that Mother would be deceived (for long) if Cousin was harming Ruth or others or deceiving us and others.

So in this matter at hand, how do we introduce and discuss issues of trust, trustgiving, and trustworthiness regarding FC? Complex matters of trust cannot be resolved – in most cases – by merely referring to ‘the science’. Of course ‘the science’ may be more or less trusted, and less or more ethically sound and trust-worthy; but giving trust and receiving trust are more complex and require more expansive and extensive relationships. In this light some may find that a caring relative – mother, brother, spouse, etc – who reports well about FC – that they perform themselves – is trustworthy, sufficiently that they might be trusted for what they say. Some may find that what a hired professional reports is trustworthy if validated by sustained observation of the FC. Some may find that some reports by the family member and/or hired professional – e.g. ‘that Ruth wants assisted dying’, or ‘that Ruth wants to be taken on a trip to Hawaii’ or that ‘Ruth refuses to go to her annual Veterans Health Care medical visit (Ruth was a WAVE in WW2, who volunteered from her rural community, as her father had volunteered and seen battle in Europe in WW1, and as her husband had volunteered (and was wounded on the D-Day landing that liberated France))- required observed validation of the FC.

So, it seems, ethically sound, to take steps before – as the authors insist – we “mount a vigorous opposition to FC”: to describe aspect of trust, trust giving, trust receiving, and trust worthiness with FC, and other augmented communications. Would that discussion learn from ethically sound process of informed consent/refusal? Would that discussion incorporate models for protecting vulnerable individuals through teams (provider, patient advocate, guardian, etc)? What else? What other considerations?

btw, I’ve asked similar questions, as have others, in Hastings Forum discussions of gender care with adolescents (and even younger children). In those discussions it seems that the settled opinion is that we MUST ACCEPT whatever the child says and that those of us who want more extensive and sustained protections are somehow evildoers. But, of course, it is true to say that children are – formally – vulnerable to coercion, misdirection, prejudicial influences, and may formally be legally incompetent to make some gender care decisions. The settled opinion flies in the face of a more extensive, expansive and reasonble discussion of trust and trustworthiness (of the available science and how providers interpret and relate the science, and, therefore of the validity of the informed consent process, and therefore of the care plan made with our without parent/guardian) and of the cultural ideologies battling over children’s distress – to make chemical and surgical gender care more freely available, or to prohibit, restrain or regulate it. If bioethics can return to discussing trust, trust giving, trust taking/receiving, and trustworthiness we will make progress on many issues.

I’m not sure how to unpack this article, having just finished reading two books by Naoki Higashida, who it seems started with facilitated communication and progressed to being able to use an alphabet chart independently, and is now a published author. I valued the insights from his books significantly given I work with children with autism. So much of what he writes about is how the inability to communicate negatively impacts his life. He does also mention how sometimes his true voice can be hard to come out, and how when making choices, he might choose something that isn’t what he actually wants, but might have caught his attention due to it’s sound, or position in the question being asked. His expressive difficulty is more than just getting out the words. I see that harm has occurred due to the use of facilitated communication but what benefits have also occurred?

This essay and the comments have shed light on new challenges that appear to exist in the field of bioethics. It appears that some may be ignoring the bedrock ethical principle of individual autonomy (in this case the ability to select your own mode of communication) in favor of other bioethics principles such as an unwavering commitment to a new and developing evidence-based practice model and its stated goals of promoting beneficence and avoiding maleficence.

Thankfully, however, individual autonomy rights have not changed with the adoption of the evidence-based practice (EPB) model. In fact, the EBP models require individual preferences and choices are respected.

The earliest pioneers recognized that the field of bioethics is a multi-disciplinary field that requires the involvement of various professionals with distinct types of training and experience. To address these potential shortcomings the field of bioethics must remain committed to an interdisciplinary study (including a proper understanding of informed consent and the proper role of guardians) so that we can ensure that all bioethics principles are never undermined by unwavering pledges to science and the EPB model and/or disagreements amongst the scientific community. The focus of bioethics must continue to safeguard a patient-centered approach and demand the medical community work collaboratively to continually expand the realm of biomedical technology.