Bioethics Forum Essay

When Might Human Germline Editing Be Justified?

Last month, an international commission convened to consider whether and how germline editing – changing the genes passed on to children and future generations — should proceed. The discussions focused mainly on the safety risks of the technology, which, while important, are not the only issues to consider. Any conversation regarding germline editing must also honestly and thoroughly assess the potential benefits of the technology, which, for several reasons, are more limited than generally acknowledged.

The vast majority of diseases and conditions stem from a complex interplay of multiple genetic and environmental factors and therefore make poor targets for germline editing. There are, however, some relatively rare conditions linked to a single gene, which might be feasible candidates for germline editing. Indeed, the framework proposed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine in 2017 to regulate germline editing limits potential applications of the technology to such conditions.

The Academies proposed framework further restricts the potential use of germline editing to prevent or treat “serious” diseases. What counts as a serious disease is up for debate, but the standard certainly is not met by germline editing on a deafness-related gene, which Russian scientist Denis Rebrikov says he wants to do.

The Academies’ framework also stipulates that germline editing may only be used in the “absence of reasonable alternatives.” Although this requirement is unclear, most agree it was not met by Chinese scientist He Jiankui’s use of germline editing to prevent paternal transmission of HIV given the existence of other means to achieve the same end (e.g., sperm washing).

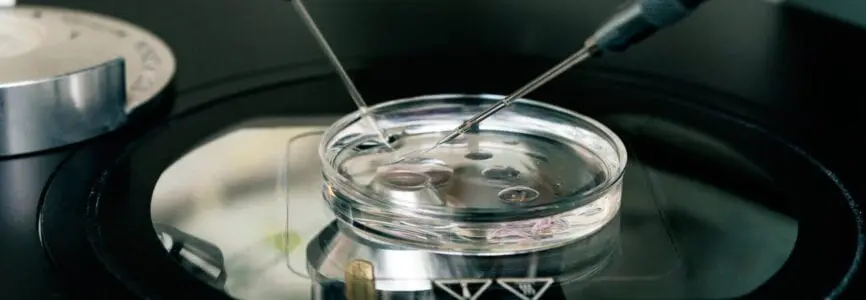

A “reasonable alternative” would also be available when a couple affected by a genetic disease can have a healthy, genetically related child by other means. Luckily, in most cases, couples can create and selectively implant some healthy embryos using IVF and prenatal genetic diagnosis. In fact, there are only two rare scenarios in which a couple affected by a serious genetic condition would not be able to produce any healthy embryos. In both scenarios, the individuals would suffer from the condition; thus, illnesses such as Tay Sachs, which result in death before reproductive age, would not qualify.

In the first scenario, each individual in a couple carries two copies of an abnormal gene that causes a recessive condition. Such a condition occurs when the abnormal gene is inherited from both parents. In this instance, all the couple’s embryos would be affected. The couple would still be able to have a healthy partially related child using gamete donation. It is therefore unclear whether such a couple would even qualify for germline editing under the Academies’ framework.

In the second case, one individual in a couple carries two copies of an abnormal gene for a dominant condition. A dominant condition occurs when one abnormal gene is inherited from one parent (e.g., Huntington’s disease). As in the first case, the couple would not be able to produce any healthy embryos, but they would be able to use gamete donation to produce a partially related healthy child.

The only type of couple that would be unable to have a healthy, at least partially related, child through existing means is one in which both individuals carry two abnormal genes for the same dominant condition (e.g., Huntington’s disease). Given the rarity of such a scenario, the unique benefit of germline editing is extremely limited in its application—a fact that must be emphasized in the discussions surrounding germline editing.

The nature of the benefit is also limited. Germline editing would not treat individuals who have genetic diseases, in contrast to somatic cell gene editing, which is currently being studied as a potential cure for genetic conditions such as sickle cell disease. Instead, germline editing would give relatively few couples the option to have a healthy, genetically related child.

While many people understandably have a strong preference for genetically related children, there are other ways to become parents. Germline editing debates therefore require an honest discussion about the reasons for preferring genetically related children and careful consideration of how far we’re willing to go to accommodate such preferences given the risks that germline editing might pose to the resulting children and society.

Although parents are bestowed with certain freedoms related to having and rearing children, as noted in the Academies’ report, no positive right to genetically related children has ever been found that could “demand that government fund or even approved new reproductive technologies.” Even if such a right did exist, however, it would not necessarily justify germline editing given that rights are rarely absolute and often bounded by other interests.

Discussions regarding the benefits of germline editing should also consider the opportunity costs entailed in pursuing the technology. The time, money, and resources (including human embryos) allocated to germline editing could instead be dedicated to research that provides a greater potential benefit (e.g., treating or curing diseases caused by genetic flaws in somatic cells) and/or benefits a greater number of people (e.g., increased IVF success rates).

Even if the risks associated with germline editing can be significantly reduced, they must still be outweighed by the potential benefits. Any discussions regarding whether or how to proceed with germline editing demand a thorough assessment of the limited benefits of the technology.

Jennifer M. Gumer, JD, is an attorney and adjunct professor of bioethics at Columbia University and Loyola Marymount University. She was a visiting scholar at The Hastings Center in July.

Bravo! This is an excellent commentary — clear and crisp. I especially endorse the claim that debates on heritable genome editing “require an honest discussion about the reasons for preferring genetically related children and careful consideration of how far we’re willing to go to accommodate such preferences given the risks that germline editing might pose to the resulting children and society.”

I have a detailed discussion about the difference between “wants” and “rights” as these pertain to the desire for genetically-related children in Baylis, F. (2017). Human nuclear genome transfer (so-called mitochondrial replacement): Clearing the underbrush. Bioethics 31(1), 7-19. DOI:10.1111/bioe.12309 and revisit this issue in my book “Altered Inheritance: CRISPR and the Ethics of Human Genome Editing”.

Also required is a global perspective that would have us look beyond personal interests to global issues. For example, could heritable human genome editing work as a prophylaxis for the benefit of huge swaths of the human family?

Thank you so much for your kind and informative comment, Dr. Baylis! I look forward to reading your cited work pertaining to the issue of preferences for genetically related children. It sounds like we agree on quite a bit.

I further agree that a thorough ethical assessment of human germline editing requires a global perspective. I’m curious if you could elaborate on your point re germline editing as a prophylaxis for the benefit of the human family. Please feel free to respond here or to email me at jmg2305@columbia.edu. I’d love to continue the conversation!