Bioethics Forum Essay

Popular Culture and Bioethics: Severance

Severance, a popular Emmy Award-winning show streaming on Apple TV+, is a rich cultural artifact. It concerns a team of office workers at a morally questionable company that performs brain surgery on employees to sever the consciousness of their work and personal lives. The four of us were so taken by the show that we wrote these reflections on its important ethical themes. Is it better to be severed and satisfied or integrated and dissatisfied? What are the risks posed by neurocapitalists who see our brains, bodies, and minds as the final financial frontier? In what ways does the trauma of moral distress and isolation experienced by the show’s characters and leading to their own quite dramatic “great resignation” echo the experiences of pandemic health care workers? What should we make of the dehumanization and alienation of corporate culture, where mindless drones cranking out widgets is rewarded and encouraged? We hope these essays-within-the-essay provide starting points for ethics discussions.

Severed and Satisfied

Welcome to Lumon Industries, where, with the flip of a switch, your outside consciousness (“outie) turns off and your inside (“innie”) turns on. This is the ultimate workspace, free of all outside distractions and, it turns out, a palliative for your outside life’s most difficult experiences. Want to escape the trauma of losing a loved one? Your complicated family? Crushing loneliness?

The severance procedure and implant make this toggle possible. And Lumon controls it (and the employees). As for the main characters—the severed workers–they seem to be doing OK, at first.

The gang finds oblivious peace in what appears to be a completely meaningless ongoing task. Their good behavior is reinforced by intermittent rewards in the form of absurd tokens, wackadoo prizes, and cult-like rituals. Dylan shows off his finger traps and pines for a waffle party, buckling down hard to finally get one. Irving embraces the rigid doctrine of Kier Egan, the company’s founder, serving as an employee handbook scholar and evangelist. And outie-Mark is just glad to not have to think about the trauma of his wife’s death for half the day.

This is living.

Not so, according to innie-Helly, who immediately wants out. After a failed attempt to get a note to her outtie (who made the decision for her to work at Lumon and holds the power to allow her to quit), innie-Helly watches a video of her outie declare that she is nothing more than an ersatz person: a phantom lacking volition and free will. She should shut up, chill out, and get to work. In response, innie-Helly attempts suicide in the Lumon elevator.

By the time all this goes down, the rest of the team is gaining insight into the fact that Lumon Industries–and the labyrinthine catacombs in which they all toil— is filled with a multitude of other severed workers. Whatever is happening to them, and with them, is not good.

Then, slowly awakened by connections to their outie-selves and to the others they care about, our protagonists begin to emerge from the darkness to find that their satiation was actually serfdom. Everything becomes clear when Dylan shuts off the machine that keeps the employees severed and we witness the momentary reintegration of their individual minds.

Like Plato’s liberated cave dweller who sees the sun for the first time, simply catching a quick glimpse of true reality is blinding and disorienting. Things are far safer and easier inside Lumon, where everyone’s difficulties are quite literally out of sight and out of mind. Under the care and protection of Kier Eagan, they can be truly fulfilled. But of what quality is this fulfillment to his severed masses?

Mill famously said, in Utilitarianism, “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied.” Severance teaches us that life is a series of hard choices between being severed and satisfied or integrated and discontented. – Dominic Sisti

Neurotech, Industry, and Severance

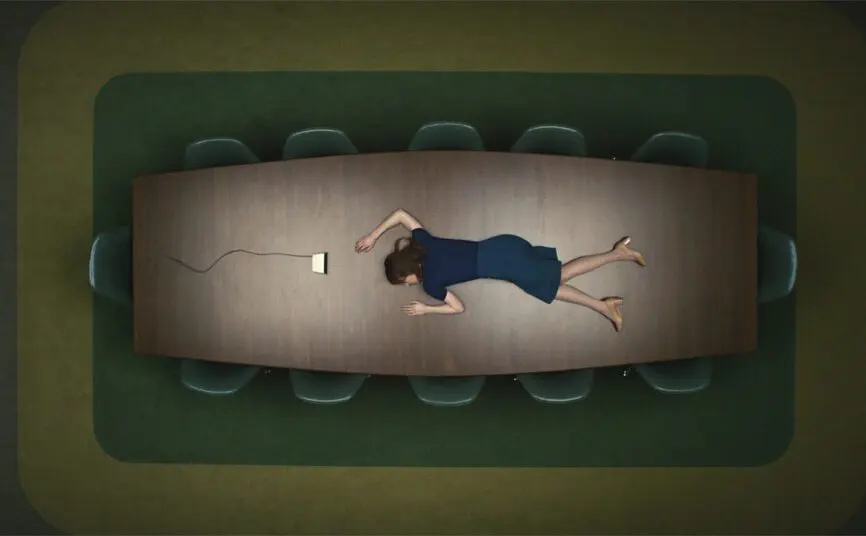

The opening scenes of Severance depict the aftermath of a unique neurosurgical procedure. Helly R. awakens face-down on a conference table, dressed in business attire and heels—not the typical setting nor apparel for post-surgical recovery. But then again, few things are typical about this neurosurgery, which has been performed by Lumon to “sever” Helly’s work memories from her nonwork ones. We see Helly providing consent to a Lumon employee and walking down a bare walkway to the operating room. The surgical equipment is branded by Lumon, as is the brain chip implanted in Helly’s head. In later episodes we learn that the neurosurgeon is a Lumon employee and that data from the personal experiences of severed employees are stored on the neural chips.

The dystopian world depicted in Severance offers a window to consider the future of neurotechnology offered for nonmedical purposes. Given the billions of dollars that have been invested in neurotechnology by Silicon Valley in recent years, such products seem closer than ever to becoming a reality. Even though most companies are currently working on neurotechnology for medical uses, some founders of neurotechnology companies, like Elon Musk, have stated that their goal is for their neurotechnology to be for nonmedical purposes, such as enhancement or communication. Furthermore, Musk’s vision of a minimally invasive neurosurgical procedure—as a quick outpatient procedure, with no hospitalization—rings true of the severance procedure, as Helly resumes work just hours after receiving her brain implant.

Today, much of the neuroethical debate about implantable nonmedical neurotechnology presumes that individuals will utilize invasive neurotechnology products outside of a work context, freely choosing when to get them and where to use them. However, it is also possible that invasive neurotechnology might one day be offered by an employer.

Severance raises provocative questions about what, exactly, the entanglements between the corporate and medical world might look like if an employer were to sponsor neural implants. Will consent processes be conducted entirely in-house or will they involve outside review? If the implantation procedure is done entirely by a robot and the chip is used for communication purposes only, will the procedure even be considered a medical one, or will it fall outside the boundaries of traditional medical regulatory frameworks? Who owns the data on the brain chip, where will it be stored, and who determines what can be done with it? What if an employee decides to have a device removed while remaining within the company, or conversely, desires to keep the device but quit the company?

While most of these questions will not arise in our immediate future, some of them—regarding consent and privacy of brain data—are already coming to the fore, as companies have begun trialing the use of wearable, nonimplantable neurotechnology in employment contexts. Thus, the blurring of the boundaries in Severance between medical and nonmedical uses of neurotechnology may be closer to reality than it initially seems. – Anna Wexler

Severed, Isolated, and Morally Distressed

Pandemic health care workers experienced distress, isolation, and stigmatization similar to what Mark and the other protagonists encounter as they navigate the sterile, labyrinthine environs of Lumon. Marketed as a high-tech solution to work-life balance, the procedure prevents employees from remembering their workdays, conveniently obscuring Lumon’s morally dubious activities. Eventually, the innies reject their dystopian reality, but are morally distressed by their inability to alert their outies.

Numerous iterations of moral distress have emerged since Andrew Jameton originally defined the term in 1984. Essentially, moral distress describes the individual’s experience of knowing the ethically appropriate action to take while lacking the ability to complete that action. Often referring to doctors and nurses, it is characterized by uncertainty, powerlessness, and an inability to meet one’s obligations, usually to patients. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, health care workers experienced this as they struggled to protect themselves while caring for infected patients. In the initial surges, time with patients decreased, PPE was reused, and constantly changing protocols barely kept pace with emerging clinical knowledge. At times powerless in the face of crisis, nurses and physicians sought to define and meet competing ethical obligations to patients, and families, to themselves, and to society.

Mark and his team also experience moral distress. The innies, increasingly aware of their involvement in something sinister, are desperate to integrate with their outies and alert them to what is going on, and yet they are powerless to do so. Though they feel they must escape, they cannot counteract the orders of their naïve outies, which keep them in Lumon.

Initially, many off-shift health care workers isolated in hotel rooms and makeshift housing to protect loved ones. This isolation compounded the stressful and scary nature of their work. The severed workers experience similar isolation. They leave and return to work in a staggered fashion, navigating near-empty parking lots at odd hours, always alone.

Mark (actually, Mark’s outie) chose severance to crush widower’s grief. His sister, who is not severed, knows this and is empathetic, but others in his outie life are simultaneously curious and disgusted. Why would he subject himself to something so unnatural and dangerous? Lumen’s impenetrability amplifies this suspect curiosity and discomfort, letting the public imagination run wild.

This revulsion is familiar to health care workers who, initially, celebrated as heroes, have since been criticized and harassed by a skeptical public that is simultaneously distrustful of science, fearful of infection, and suspicious of anyone who chooses to work in health care. During early surges, hospitals restricted public entry to limit viral spread, compounding this fear and repulsion.

“Am I livestock?” Helly asks on her first day at Lumon. Is she dispensable? Do her humanity and safety matter? Severance does not deal with ethical conflicts specific to patient care, and Lumon does not provide health care. However, experiences of frontline workers in both spaces share important commonalities: Huddled together, isolated from the world-at-large, misunderstood, ridiculed, and stigmatized, they are the faces of industry work too unseemly to share or too terrifying to acknowledge. They bear the burdens of doing the work that no one wants to see. – Aliza Narva

Severance and Semblance

As a new generation demands changes in the workplace–including the right to authenticity in the office–Severance has rediscovered alienation, this time with a neurotechnology that introduces an overt division of the self.

Subtract that bit of 21st century high-tech conceit and you have in essence the problem with industrialization that philosophers, cultural critics, and artists have been noodling for at least 200 years. In that respect Severance is more than a commentary on work-life balance. It stands in a grand tradition of modern alienation.

For a Marxist the shadowy bosses at Lumen and the (assembly line) workers are trapped in the same abasement of human nature, despite the apparent power imbalance:

“The propertied class and the class of the proletariat present the same human self-estrangement. The former class feels at ease and strengthened in this self-estrangement, it recognizes estrangement as its own power and has in it the semblance of a human existence. The class of the proletariat feels annihilated in estrangement; it sees its own powerlessness and the reality of an inhuman existence.” (Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Holy Family, 1845, emphasis in original).

By the end of the 19th century as industrial capitalism took hold even nonradicals like William James observed, in his Principles of Psychology (1890), the way that the habits of work life set in by age 30, “the ways of the shop,” like folds never to be released. A few years later Frederick Winslow Taylor broke work into bits (“scientific management”) and Henry Ford made a fortune putting Taylorism into practice, much to the fury of the labor movement then getting organized.

At Lumon, Taylorism is thoroughly soulless. As long as the quota is met, who really cares what they are doing at their compartmentalized screens?

Around the same time in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber argued that Puritan values aligned with hard work merged in an ennobling and progressive spirit to create a sense of calling that idealized the productive system, largely immunizing it from criticism on moral grounds like exploitation. Fifty years later, in his best-seller The Organization Man, William H. Whyte protested conformity to the demands of the company and the supposed wisdom of the corporate collective. Emerging from two world wars and the Great Depression, Whyte argued that the entrepreneurial ideal of the Protestant ethic had given way to an oppressive philosophy of management. The Organization Man in some ways anticipated the efforts by well-off white men in the 1960s to find more meaning in their lives.

Since the 1970s, civil rights movements have left in the dust the image of the corporate worker as typically white, male, and commuting from Greenwich to Manhattan. Women and people of color have long been part of the workforce, but they have done so amid worsening economic inequality and ever greater demands for productivity and the demands of investors and corporate boards for signs of growth in every quarterly report. In the 1990s the comic strip Dilbert and TV shows like The Office and The Simpsons captured this simmering dissatisfaction. Ultimately, these satires weren’t enough. It was just a matter of time and circumstance before the frustrations of this paradox stimulated a protest against office culture. The dislocations of the pandemic have provided the occasion for it to burst forth.

Severance tells us that the system can only save itself by dividing the self. In season two it merely remains for the severed to rage against the machine. – Jonathan D. Moreno

Dominic Sisti, PhD, (@domsisti) is an associate professor of medical ethics and health policy and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Anna Wexler, PhD, (@anna_wexler) is an assistant professor of medical ethics and health policy at the Perelman School. Aliza Narva, JD, MSN, RN, is the director of ethics at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Jonathan D. Moreno, PhD, (@pennprof) is the David and Lyn Silfen University Professor of Ethics at the University of Pennsylvania and a Hastings Center fellow.

[Photo: Apple]

This is so very fascinating….I must look up this series…thank you all for your analyses…