Bioethics Forum Essay

Jimmy Carter’s Defeat and the Seeds of Hope

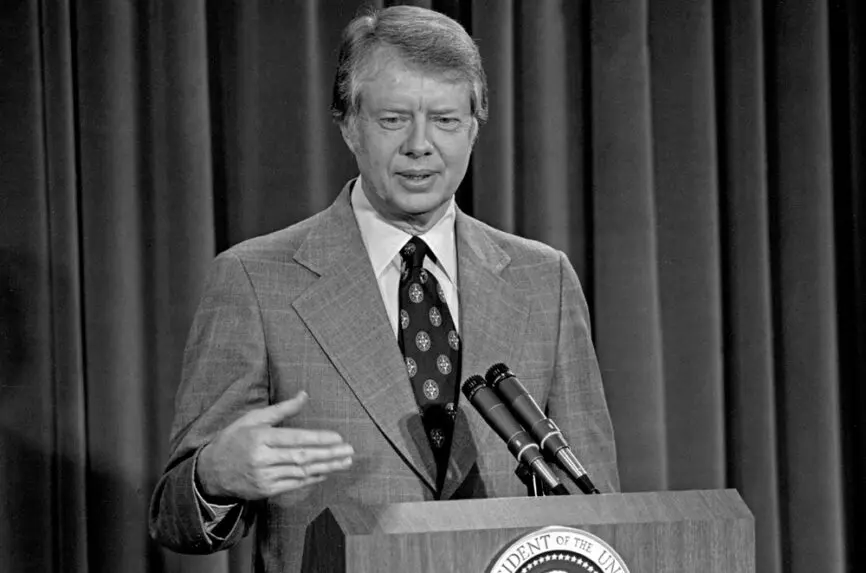

I last saw Jimmy Carter in person on November 4, 1980. He had yet to have his illustrious post-presidential career, and I had just dropped a bioethics course in college. But the future would unfold in ways that brought bioethics into both of our lives.

I was covering election night for Wesleyan University’s WESU-FM with my college roommate. It had been an eventful day. We interviewed Civil Rights activist Jesse Jackson; Stuart E. Eizenstat, who served as Carter’s domestic policy advisor; and Phil Jones of CBS News. We even had a good conversation with the presidential historian, Richard Norton Smith. But the major event was Carter’s concession speech.

I had Secret Service press credentials and was close to the stage at the Sheraton Wardman Park Hotel in Washington as Carter came out to speak. There was a huge American flag draped behind the stage. The president was flanked by family and supporters.

To the annoyance of many Democratic candidates, Carter acknowledged his loss before the polls closed out West. They feared that his candor would suppress turnout and extend the president’s misfortune to their own campaigns.

But it was as clear as day, early that night, that Carter would lose in a landslide to Governor Reagan. But no matter. Carter was just being Jimmy, candid, and honest about the circumstances. There was no point in prolonging the inevitable. Facts were facts and it was time for him to move on.

In what seemed at the time a pedestrian speech, he graciously conceded. With his signature grin he told us, “The people of the United States have made their choice, and, of course, I accept that decision but, I have to admit, not with the same enthusiasm that I accepted the decision four years ago.” He continued, “I have a deep appreciation of the system, however, that lets people make the free choice about who will lead them for the next four years.”

Carter said he had called Ronald Reagan and “congratulated him for a fine victory” and sent a telegram in which he pledged “our fullest support and cooperation in bringing about an orderly transition of government in the weeks ahead.”

It all seemed rather predictable at the time, indeed almost defeatist given the ongoing vote out West. But writing today, on the fourth anniversary of January 6, 2021, I find that Carter’s actions take on a patriotic hue, all the more so because Carter was only 56 years old. His political career was over. Yet, despite the personal toll of the loss, he was able to jest about the results and uphold the rule of law.

This is too easy to forget through the distortions of history. At the time, his brilliant post-presidential career, crowned by a Nobel Peace Prize, was still ahead of him. In retrospect, his future success seemed secure, almost inevitable. But at that moment it wasn’t guaranteed or even conceivable. One can only imagine his disappointment. Kirkegaard’s adage that life is lived forward but understood backwards comes to mind. Carter’s rich future was still ahead of him.

History’s focus on Carter’s post-presidency can also obscure his genuine accomplishments while in office, especially the less prominent ones that did not make headlines, like the Camp David Accords, the Panama Canal Treaty, or even the solar panels on the roof of the White House, which President Reagan ceremoniously removed. Then there is also the overhang of the Iran hostage crisis, inflation, gas shortages, and the infamous malaise speech. All of these events tend to commandeer history. But they are only a part of the record.

For those of us in bioethics, it is important to recall Carter’s contributions to our field. As President, Carter was the recipient of the landmark 1978 Belmont Report written by the National Commission Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. Chairman Kenneth J. Ryan submitted the Report to the President on September 30, 1978.

Carter was in office and oversaw the subsequent President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research. He appointed the 11 original members of the commission in July 1979, including its chair Morris B. Abraham and luminaries like Renée Fox and Al Jonsen.

These details are but footnotes to Carter’s presidency and could easily be forgotten. But they need to be placed into the context of Carter’s biography and appreciated as important precursors to President Carter’s — and the Carter’s Center’s — commitment to global health equity such as efforts to eradicate Guinea Worm and River Blindness. And more generally, promoting human rights and discourse over conflict.

There is a through line from the Belmont Report to work of the late President and the Carter Center over the ensuing decades. He promoted autonomy by securing free and fair elections across the globe. His work in global health was beneficent and his focus on the health needs of underserved regions in the world spoke to a commitment to distributive justice. His principled life embodied the very best of principlism, a life of practical idealism and service.

These exemplary accomplishments were of course unknowable to those of us watching President Carter’s concession speech back in 1980. But perhaps the seeds were sown for this former peanut farmer with a rich harvest of accomplishment to come. His life at that moment was an ode to potentiality, a reminder of what still might yet be achieved after life’s nadirs.

Election night 1980 seemed like a final chapter but it was in fact a prelude to a life pursuing the good. One can only hope that Carter’s connection to the early days of bioethics helped to guide the arc of his moral universe. It would be a legacy of which our field could justifiably be proud.

Joseph J. Fins, MD, D. Hum. Litt. (hc), M.A.C.P., F.R.C.P., is the E. William Davis Jr. M.D. Professor of Medical Ethics, a professor of medicine and chief of the division of medical ethics at Weill Cornell Medical College; Solomon Center Distinguished Scholar in Medicine, Bioethics and the Law and a Visiting Professor of Law at Yale Law School; and a member of the adjunct faculty at the Rockefeller University. He is a Hastings Center fellow and chair of the Center’s board of trustees.

Well said Joe. Thank you.

“His life at that moment was an ode to potentiality, a reminder of what still might yet be achieved after life’s nadirs” Thank you for this beautiful and illuminating essay…

Thank you for this beautiful tribute, Joe.

Joe Fins’ reflections on Jimmy Carter, anchored in his presence at the Sheraton Wardman Park Hotel on the evening of Nov. 4, 1980, as the President “graciously conceded” to Ronald Reagan, is, as we’ve come to expect from Joe, beautifully composed and rich with insights. At the moment, many of us are pausing to think with gratitude about the late president’s life of service and his devotion to democracy, in which concessions are followed by an orderly transfer of power, as we witnessed again yesterday as Kamala Harris, like Carter in 1980, put aside the pain of loss and presided with dignity over the counting of the Electoral College votes and the certification of Donald Trump as the 47th president. For two reasons, however, I am not convinced by Joe’s suggestion that President Carter’s “connection to the early days of bioethics helped to guide the arc of his moral universe.”

First, while it is fair to say, as Joe also does, that Carter’s “life of practical idealism and service” illustrates “the very best of principlism”—an ethical framework that is widely employed in bioethics—Carter’s principles derive not from bioethics but from his religious faith. The principles of bioethics themselves rest on “the common morality,” which in Western society is deeply connected to religious doctrines that support duties to avoid harm and to do good (especially for those who are less fortunate), and to respect the dignity and sanctity of life. The principles can be expressed—as they were in Carter’s laudable post-presidential achievements—through “autonomy” and “beneficence,” as Joe puts it, or in terms of human rights as well. And, of course, Carter’s oft-overlooked but very substantial achievements as president—such as articulating the need to produce energy in a sustainable fashion (a reflection of the “stewardship” that, in his view, man was expected to exercise over God’s creation) and the Camp David Accords and subsequent Egyptian-Israeli Treaty (a remarkably durable peace that depended on President Carter’s direct involvement and his faith that the three nations in the Abrahamic tradition could achieve harmony)—are more a manifestation of religious belief than of bioethics.

The second reason for doubting that Carter felt a deep connection to—much less took inspiration from—bioethics is that this was an issue associated with Senator Edward Kennedy, who had sponsored both the provisions in the 1974 National Research Act that led to the creation of the National Commission in 1974 and to its Belmont Report in 1978, as mentioned by Joe, and the statute, passed in November 1978 that authorized the President’s Commission. Carter’s slow response in appointing and funding the latter commission—whose members weren’t sworn in until January 14, 1980—reflected his annoyance that in 1979 Senator Kennedy was planning—and stirring up a “grass roots” movement to “persuade” him—to run for president. A further indication that the Carter White House was not concerned with bioethics can be found in the decision of the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare (as the department was then known) to dissolve the Ethics Advisory Board, which was created based on a recommendation by the National Commission for a mechanism to review research proposals involving especially vulnerable subjects before the government could fund them. (On May 4, 1979, the EAB recommended accepting protocols for research involving human embryos up to 14 days old, a report that was never acted on by the secretary or any of her successors.) In disbanding the EAB and moving its funds to the President’s Commission, the secretary stated that the board was made unnecessary by the commission, even though the statute creating the latter explicitly excluded it from providing advice on individual projects, which was the board’s mandate.

I think, Joe, that bioethics needs to rest on its own laurels, without claiming to have inspired President Carter’s, about which you have written so eloquently.

I appreciate the gracious and generous comments of those who responded to my essay paying tribute to President Carter, especially Alex Capron’s thoughtful analysis. He is quite right there was no love lost between Carter and Teddy Kennedy and of Senator Kennedy’s role in the passage of the National Research Act of 1974 and the establishment of the early commissions. The more important point, that I want to address, is the relationship of Carter’s religious beliefs and bioethics. I quite agree that the bioethics of Belmont drew upon the common morality. I was arguing, perhaps in a eulogistic or aspirational manner, that in many ways Carter’s ethic was actually more faithful to the origins of that common morality than the secularized version that the field has come to embrace. Over the decades since Belmont, what emerged as the common morality favored rights over its antecedent sources in religion. In a paradoxical manner it became parochial and emblematic of mid-century liberalism, an argument made by the sociologist, John H. Evans in The History and Future of Bioethics: A Sociological View. That parochialism, heavily secular and drawing upon the law, has had its unintended consequences by narrowing the base for consensus on contentious issues that have divided society. Dan Callahan made this point in his 1990 Hastings Center Report essay, “Religion and the Secularization of Bioethics.” Callahan observed that the dependence of bioethics on the law with its marginalization of religious sources of wisdom made it “too heavily dependent upon the law as the working source of morality.” Because of this, bioethics was left “bereft of the accumulated wisdom and knowledge that are the fruits of long-established religious traditions.”

My point in asserting that Jimmy Carter’s lineage could be traced to the principles of Belmont was to maintain that he was truer to the origins of bioethics, given his religious faith, than to its subsequent secular and legalistic iterations. This adherence has had it benefits because Carter was seemingly able to reconcile so many of the contradictions of modern American life.

What is truly remarkable about Carter, indeed the brilliant paradox which was his life, was that he was religious but not parochial and an evangelical Southern Baptist who was also a progressive pluralist. He firmly believed in the separation of Church and State both on a constitutional basis and as a Biblical injunction, was pro-life and pro-choice and in 2018 stated that “I believe that Jesus would approve of gay marriage.” The confluence (and wonderful contradiction) of his beliefs is beautifully articulated in his 2005 volume, Our Endangered Values: America’s Moral Crisis whose first chapter is fittingly entitled, “America’s Common Belief – And Strong Differences.”

Finally, speaking of provenance, it is interesting that in Endangered Values Carter confesses that he “found Reinhold Niebuhr’s books to be especially helpful.” Neibuhr, the distinguished Christian Ethicist, also had a profound influence on Professor James Gustafson of Yale Divinity School who trained many of the founders of the field in the 1960’s including Al Jonsen, Stanley Hauerwas, LeRoy Walters, Jim Childress, and Tom Beauchamp and was closely linked to Paul Ramsey, James Drane and later Mark Siegler and Lisa Cahill. Of course, Jonsen, Childress, and Beauchamp all had links to bioethics commissions and Beauchamp and Childress were later the proponents of principlism as a method of bioethics. (See Shulman KS and Fins JJ. Before the Birth of Bioethics: James M. Gustafson at Yale. Hastings Center Report 2022;52(2):21-31. DOI:10.1002/hast.1352)

My point in writing that, “One can only hope that Carter’s connection to the early days of bioethics helped to guide the arc of his moral universe” and that “it would be a legacy of which our field could be justifiably proud” was to note that Carter’s life embodied the principles of Belmont. These principles existed long before the birth of bioethics and were embodied in the Abrahamic faith traditions which so informed Carter’s world view and his life in this world.

Again, I am immensely grateful for Alex Capron’s ever thoughtful views and for being prompted to explore these issues

Jimmy Carter was less interested in the bioethics of quandaries than of virtue. He was a fine role model of humility, as not in thinking less of self but in thinking of self less. In all the small details of life he never wasted energy on self-promotion. Humility left space in the room of life for others. Self-inflation, as with Gustafson, was contrary to a proper theocentric appreciation for the glory of the Supreme and Ultimate Reality, for the place of awe, kindness, and calling. It was virtues first, and an abiding spiritual feeling that it is better to be always kind than always right, for human reason, as Reinhold noted, more readily veers toward self-interest than purity. Reinhold weite that the children of light should have the cunning of the children of darkness- pardon his old metaphors- but none of their malice. Everyone who worked with Jim Gustafson or with Jimmy Carter understood them as humble theocentrists for the most part.