From Bioethics Briefings

Family Caregiving

Highlights

- Most long-term care to older adults is provided at home by family caregivers.

- Changes in demographics, workforce patterns, and health care economics have increased the need for—and complexity of—caregiving.

- Family caregivers are often marginalized by health care professionals and denied access to information that they may need to do a good job.

- Bioethics has traditionally focused on patients, but has recently explored the unmet needs of family caregivers.

- An understanding of the ethical concerns can help policymakers improve the quality of caregiving and the well-being of caregivers.

Framing the Issue

Families have always taken care of their ill and disabled relatives. Why should it be any different now? This disarmingly simple question often opens a policy discussion of the role of families in providing care to aging or chronically ill family members. Underlying this question is an assumption that families should do everything they did in the fondly misremembered Good Old Days—and do it all on their own. In hospitals and other health care facilities, however, professionals often turn the question on its head: Why don’t all these meddlesome families just stay out of our way? We don’t have time for them.

Although family caregiving has always been an important kinship obligation, changes in demographics, workforce patterns, health care economics, and service delivery have resulted in a dramatic change in its extent and complexity. In this changed environment, what values should guide public policy in responding to family caregivers’ needs? Should bioethics, which has traditionally stressed the primacy of individual autonomy, incorporate family caregivers’ interests in addressing decision-making, especially in long-term care?

What’s Different Now: Just about Everything

Since the 1950s, one of the foundational aims in bioethics has been to uphold patients’ rights to be informed and to make their own decisions. The intention was to reduce “paternalism,” the tendency of physicians to make some decisions for the good of their patients without their consent. While consent remains a cornerstone of bioethics, a sea change in caregiving needs and practice has given rise to a new set of ethical issues that concern caregivers themselves.

Age. The U.S. population is aging. There will be fewer caregivers to support the aging population, as the caregiver radio–the number of people theoretically available to support an older adult–declines from 7.2 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2030. A longer lifespan can mean many more productive and satisfying years, but it can also mean years of illness, frailty, and dependence. Dementia has become a major health problem.

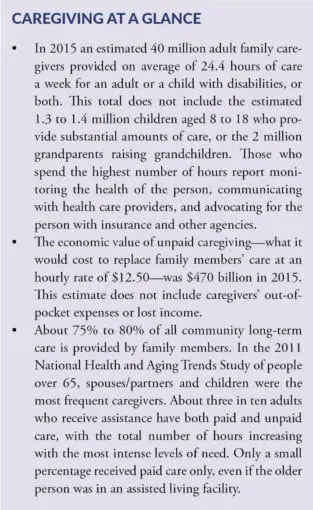

Care at Home. Long-term care is often mistakenly assumed to be nursing home care, but in fact the majority of long-term care for older people is provided at home by family members. The move from hospital-based care to care at home, as part of cost-containment efforts, has accelerated this trend.

Gender. Women, the traditional providers of family care, are now in the paid workforce in greater numbers. About 40% of all adult caregivers are men, but women continue to provide most of the day-to-day personal and household care. Half of family caregivers are employed full- or part-time. Family caregivers who leave their jobs to provide care lose not only current income and access to health insurance, but also future Social Security benefits, retirement income, and job opportunities when caregiving ends—usually many years later.

Technology. Homes filled with all the trappings of a hospital room are subtly changed from havens of comfort and security to places of anxiety and sadness. Family caregivers are expected to provide the level of care that only a few decades ago was reserved for hospitals. But they are typically not trained or supervised. While assistive and monitoring technology, including robots, may in time relieve some caregiver responsibilities, so far these devices have not been adopted widely.

Family structure. Family caregivers can be related by blood or marriage, but they can also be domestic partners or friends. Changes in family structure have not diminished the basic instinct of people to care for others, but the health care, legal, and policy systems have not kept pace with these changes. It is often difficult for caregivers in nontraditional relationships to carry out their responsibilities. Such difficulties are compounded with family caregivers from minority or immigrant groups, who may have language barriers or religious practices that are unfamiliar to mainstream medical practitioners.

The Cultures of Caregiving: Common Ground amid Conflict

Families and the U.S. health care system have distinct cultures. Therefore a family member will approach the task of caring for a sick or an elderly person with a different set of priorities than a hired caregiver or a policymaker. Whatever their differences, families are characterized by relationships established by blood, marriage, or commitment. Family members’ obligations to one another are moral, rather than legal (except in certain circumstances). In contrast, the health care system is dominated by the culture of Western medicine, with its primary values of scientific evidence, oversight (legal, regulatory, and professional), efficiency, objectivity, confidentiality, technological solutions, and hierarchical organizations.

In our health care system, the patient, not the family caregiver, is legally entitled to receive services. (The exception is hospice, in which the family is the unit of care.) Policymakers’ responsibilities include stewardship of scarce resources, which means balancing individual needs and community resources. They value cost-effective programs that serve populations, not case-by-case solutions, and expect individuals to draw upon personal or family resources as a first and perhaps only step.

Bioethics, with its traditional emphasis on individual patient autonomy, may have had an unintended consequence of relegating the family to a subsidiary, or even a negative, role. Controversial cases make news and material for bioethics commentary. They almost always involve family disputes about prognosis (as in the Terri Schiavo case), a family’s refusal to accept medical advice (as in the “Baby K” case, in which a parent insisted on treatment for an anencephalic newborn), or accusations of medical neglect and financial mismanagement (as in the Brooke Astor saga). Many cases that do not come to public attention do come before institutional ethics committees, where family members may be described as dysfunctional and confrontational. Such families do exist, and others become confrontational when faced with what they perceive as failures to provide information, treatment decisions made by insurance companies, and discrimination of various kinds. Several writers in bioethics, such as Hilde Lindemann, Jamie Nelson, and Martha Holstein, have begun to shift the balance in bioethics so that family interests are weighed in concert with—not against—patient autonomy. A holistic view of a patient as person nearly always includes family.

Recognizing the differences in worldview between families and the health care system is the first step toward reducing conflict and finding common ground. An article in Academic Medicine in 2008 suggested that the first step in teaching “cultural competence” (in the traditional ethnic sense) to medical students is to teach that medicine has its own culture. “Physician, know thyself,” the title of the article, could well be applied more broadly: “Family caregiver and policymaker, know thyselves.”

An Ethical Framework for Public Policy

Most of the arguments for supporting family caregivers rest on economics: family caregiver assistance is essentially irreplaceable. Beyond the loving relationships embodied in family care, there is simply not enough money, nor are there enough workers, to replace family members as the broad base of the workforce. As the 2007 AARP issue brief on family caregiving puts it, “Adequate funding for family caregiver support will provide an excellent return on investment.”

Ethical reasons are equally important. Public policy that supports family caregiving embodies the widely held view that families are intrinsically important because they give meaning and depth to fundamental human relationships. Furthermore, family caregiver support enhances patient care, a primary professional value.

Family caregivers’ willingness to help does not remove all responsibility from policymakers, nor from health professionals, community organizations, and society in general. Family caregivers are not resources to be used until exhausted; they are true partners in care. Their mental and physical health and well-being are legitimate causes for concern for bioethicists, public health officials, and medical professionals.

In ethical terms, the argument for supporting family caregivers can be made on the grounds of beneficence and justice. Beneficence, or respect for persons, may not raise any special concerns with regard to family caregiving, unless there is a perception that a patient’s interests or needs are compromised by the needs and wishes of the caregiver. However, justice, or the fair distribution of goods and services, raises many unresolved questions in family caregiving:

- With limited resources, which family caregivers should be targeted for support services?

- Should this support be based on income or vulnerability, or should it be more broadly available?

- Are there certain tasks that require professional-level skill that families should not be expected to do?

- When is it unreasonable to expect family care to continue?

- When children and teenagers provide care, should professionals set limits or intervene if parents or guardians don’t?

- Should family caregivers of people with behavioral or cognitive problems and family caregivers of people with physical disabilities be treated equally?

- What should be the balance between supporting family caregivers and providing care to those without family?

- Does the principle of justice extend to gender divisions of labor within a family?

Support for Family Caregivers

Several federal, state, and private programs offer limited financial and other assistance to family caregivers. Notably, however, few of these programs or proposals address the relationship between the family caregiver and health care providers. There is a large unmet need for help.

Federal programs. The first federal program specifically to address family caregivers was the National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP), established in the amendments to the Older Americans Act of 2000 and now administered by the U.S. Administration on Aging, a program division within the U.S. Administration for Community Living. The program provides money to state Area Agencies on Aging to support information and referral services, training, counseling, and occasionally financial aid to family caregivers of people over the age of 60. Specific funds are earmarked for Native American tribes and grandparents raising grandchildren. States area required to match federal funding with a 25% contribution. Funding levels have ranged from an initial level of $120 million in 2001 to a high of $156 million in 2006, but since 2013, have been stable at $146 million.

The Lifespan Respite Care Act was passed in 2006 and provides competitive funds to states to develop coalitions of organizations that provide respite care services for family caregivers of adults of all ages and children with special needs. Since 2009, federal funding has been level at approximately $2.35 million a year. As of 2015, eligible state agencies in 33 states and the District of Columbia have received initial three-year grants of up to $200,000.

The Alzheimer’s Disease Supportive Services Program has evolved since 1992, when the Administration on Aging began funding demonstration grants to state programs. Since 2012, funding for this program has ranged from $3.7 million to $4 million a year. Seventeen states and communities are administering grants that support activities in dementia care. About 61% of caregivers served through the National Family Caregiver Support Program are caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease or a related dementia.

Several proposals have been made to give family caregivers tax credits, generally at $3,000, counting time taken from employment toward Social Security credits, and other financial supports. None of these proposals has been enacted.

State activities. Most of the public activity on family caregiving occurs in state governments, which fund agencies to provide information, referrals, some in-home support, as well as caregiver assessment, and respite services. These activities typically are called “long-term services and supports” (LTSS) and are funded through waivers to federal Medicaid funding, with the goal of delaying nursing home placement as long as possible. Some states have “cash and counseling” programs that allow people with disabilities to choose either to use home health aides from agencies or to hire their own attendants. They generally choose to hire—and pay—family members. In some states spouses cannot be paid workers. The total paid to a family member cannot exceed the amount that would have been paid to an agency. In addition, some states have modest tax credits for family caregivers, generally around $500. The family member must be a financial dependent of the caregiver.

Employment programs. In 2004 California inaugurated a program to provide a percentage of income to family caregivers who take a leave from their jobs. New Jersey, Rhode Island, and New York (in 2016) are the only other states to pass such legislation. The programs are funded by employee contributions. Some large corporations have “work-life” programs for family caregivers, including flex time, telecommuting, and referrals to employee assistance programs. Some states and municipalities have added “family caregiver” to their list of employees protected from discrimination.

Caregiving Policy Agenda

There are several ways that public policy can improve the quality of caregiving and the well-being of family caregivers. Fostering better communication and coordination of care, as well as professional development, should lead the agenda.

Communication. Patients’ rights need to be balanced against family caregivers’ needs for information. It can be extremely difficult for family members to get information about the medical condition of a relative for whom they provide care. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and the Privacy Rule implementing it in 2003 have caused consternation among many family caregivers. Although the law was not intended to change clinical practice or inhibit communication between providers and family caregivers, many health care providers have interpreted it as a warrant to withhold all information without a patient’s written consent for fear of criminal liability and severe fines. Family caregivers, dependent on health care professionals to give them clear guidance and directions, now commonly hear, “I can’t tell you because of HIPAA.” The act has bolstered the view that families are nuisances and need not be part of decision-making. Public policy will have to address this issue and provide recourse for family caregivers who cannot obtain vital information for their caregiving responsibilities. On the other hand, there are clear instances in which competent patients prefer to keep their medical information totally private, even from family caring for them. Discussion and resolution of these instances should be a fruitful exercise for clinical bioethics.

Care coordination. Many health care organizations are concerned about improving the coordination of care, especially during transitions between care settings. Efforts to improve care coordination have been combined with initiatives to reduce hospital readmissions, which now carry financial penalties. Poor communication and incomplete information have been shown to lead to medical errors, mainly involving medication management. Efforts to improve transitional care to date have focused on provider-to-provider communication, but family caregivers are typically left out of care planning, even though they are often the day-to-day care coordinators. Including family caregivers goes against current practice; yet it is essential for quality care. Ways to involve family caregivers, assess their needs and limitations, and plan accordingly need to be on future policy agendas.

Workforce development. Another critical policy issue is to increase the number of professionals and paraprofessionals trained in geriatrics and willing to work in home settings. These people are in extremely short supply. The development of career ladders for home care aides and incentives for physicians and nurses to specialize in geriatrics will be needed to support future patients and family caregivers.

Family caregiving is not a just a “woman’s issue,” an aging issue, a health care issue, or a social service issue. It affects everyone at some point in their lives. Family caregiving is at the boundary of public and private realms, and policymakers must tread carefully to preserve family values while crafting public solutions to caregiving needs.

Carol Levine, MA, a Hastings Center Fellow, is a senior fellow at the United Hospital Fund and former director of its Families and Health Care Project. In 1993 she was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship for her work in AIDS policy and ethics.

45% of our work is supported by individual donors like you. Support our work.

Resources

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Families Caring for an Aging America (2016)

- United Hospital Fund, Families and Health Care Project, Next Step in Care. This website includes guides for family caregivers on navigating transitions in health care and guides for health care providers on working with family caregivers.

- Family Caregiver Alliance. Includes fact sheets on many aspects of federal and state family caregiving policy and other topics.

- National Alliance for Caregiving. Includes results of national surveys of all caregivers, caregivers of different ages, and caregivers of people with severe mental illness.

- Louis D. Burgio, Joseph E. Gaugler, and Michelle H. Hilgeman, eds., The Spectrum of Family Caregiving for Adults and Elders with Chronic Illness (Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Lynn F. Feinberg and Carol Levine, “Family Caregiving: Looking to the Future,” Generations, Winter 2015.

- Susan C. Reinhard, Lynn F. Feinberg, Rita Choula, and Ari Houser, “Valuing the Invaluable: 2015 Update,” AARP Public Policy Institute, July 2015.

- Ira Byock. The Best Care Possible. (Avery, Penguin Group. 2012).

- Nancy Folbre, ed. For Love and Money: Care Provision in the United States (Russell Sage Foundation, 2012).

- Susan C. Reinhard, Carol Levine, and Sarah Samis, “Home Alone: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Chronic Care,” AARP Public Policy Institute and United Hospital Fund, 2012.

- United Hospital Fund, Families and Health Care Project. “An Ethical Framework for New York State Policy Concerning Family Caregivers,” November 2006

- Carol Levine and Thomas H. Murray, eds. The Cultures of Caregiving: Conflict and Common Ground among Families, Health Professionals, and Policy Makers (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004).

- Eva F. Kittay and Ellen K. Feder, eds. The Subject of Care: Feminist Perspectives on Dependency (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2003).

- Hilde L. Nelson and James L. Nelson, The Patient in the Family: An Ethics of Medicine (Routledge, 1995).

- Hastings Center Resources on Family Caregiving

Experts

- Carol Levine, MA

- Lynn Friss Feinberg, MSW

- Kathleen Kelly, MPA

- Jennifer Wolff, PhD