Bioethics Forum Essay

Ethical Considerations for First-In-Human Pig Kidney Xenotransplant Clinical Trials

Approximately 90,000 of the more than 100,000 people currently on the national organ transplant waiting list need a kidney. The demand for kidneys far outweighs their availability. One potential alternative source of transplantable kidneys is xenotransplantation, transplanting animal organs into humans.

The first clinical trial transplanting gene-edited pig kidneys into humans could start this year. Pig kidney clinical trials raise important ethical issues, including: Who should be eligible to participate? What information do patients need to make informed decisions about participation? What, if any, financial incentives should research teams offer to encourage participation? How should trial investigators ensure that the potential benefits of these trials outweigh the potential harms, including the possibility of a pig infectious disease being transmitted to a transplant recipient? Should trial investigators require participants to agree to lifelong monitoring for such diseases?

To facilitate the ethical development, oversight, and conduct of pig kidney clinical trials, we developed a set of practical tools from our four-year study, which was funded by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health. We produced:

1) four clinical case studies and a teaching guide for xenotransplant research teams;

2) a decision aid for kidney patients recruited to participate in pig kidney clinical trials;

3) an informed consent prototype for xenotransplant research teams to give to prospective participants;

4) a checklist to assist institutional review board members reviewing protocols and informed consent forms for pig kidney clinical trials; and

5) recommendations for transplant teams, sponsors, and transplant programs conducting pig kidney clinical trials, IRBs that review pig kidney clinical trial protocols, and transplant regulators.

These materials were informed by many sources, including: a 17-member advisory committee comprised of transplant clinicians, transplant recipients, a living donor, xenotransplant researchers, transplant regulators, transplant health services researchers, and experts in human research ethics; a survey with patients on the kidney transplant waiting list; and in-depth and usability testing interviews with patients on the kidney transplant waiting list, transplant experts, and IRB chairs and other research ethics experts.

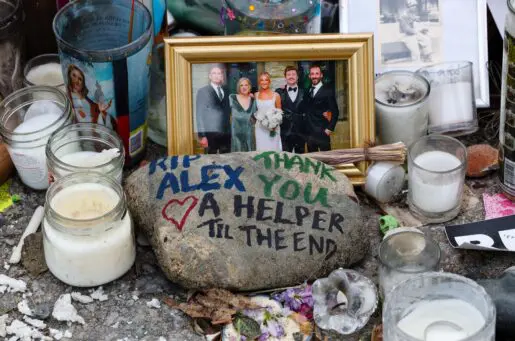

Several key developments have paved the way for initiating a first-in-human pig kidney clinical trial. Since 2021, experimental xenotransplants have been conducted to learn if a gene-edited pig kidney and pig heart work in a human body. Some of these experiments were with deceased human bodies and others were with patients with advanced kidney disease. Four xenotransplants with kidney patients were conducted under the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Expanded Access, or compassionate use, pathway, which is designed for certain patients with serious conditions to get them access to an investigational medical treatment.

The first patient who received a pig kidney died within two months post-transplant. The second recipient lived three months after receiving a pig kidney and a mechanical heart pump, though the pig kidney had to be removed 47 days post-transplant because it was damaged due to limited blood flow related to the heart pump. The third pig kidney recipient is back on dialysis after the kidney stopped working and was removed four months post-transplant. The fourth pig kidney recipient still has the kidney, and it is functioning after six months.

The pig kidney xenotransplants conducted under the FDA’s Expanded Access pathway have provided important preliminary information about whether a gene-edited pig kidney is safe for humans and how well the kidney functioned in the recipients. However, to obtain valid and reliable scientific data about the safety and efficacy of pig kidney xenotransplants, clinical trials are needed.

We summarize below several key ethical considerations for conducting a pig kidney clinical trial that our study identified.

Eligibility Criteria

To obtain sound scientific data about the safety and efficacy of pig kidney xenotransplantion, clinical trial sponsors will need to establish eligibility criteria for participation. This means that some patients who are willing to participate will not be invited to do so. Some commentators suggest that to be eligible, patients should be on the waiting list for a human kidney, while others point out that some patients who are not on the waiting list might be good candidates for trial participation. We decided that being on the waiting list should not be a criterion because, for various reasons, many patients never get waitlisted even though they qualify.

Informed Consent

We developed a patient decision aid and informed consent prototype to help patients who are considering whether to participate in a pig kidney clinical trial. Patients we interviewed expressed interest in xenotransplantation, but their interest in participating in a pig kidney clinical trial was tempered by the risk of getting an infectious disease from the kidney. Patients also indicated that their willingness to participate would depend on how long they would have to wait for a human kidney, the seriousness of their health, and how long the pig kidney would function. To make an informed decision about whether to participate, patients said that they would want information about the source pig and its kidney; the risks and benefits of trial participation; the experience of previous pig kidney clinical trial participants; and the logistics of a pig kidney clinical trial.

Patients also said they wanted to know what would happen if the pig kidney failed. Clinical trial sponsors should establish an “exit strategy” for recipients whose pig kidney no longer works.The informed consent process should include a discussion of the options that might be available to them, such as a human kidney transplant or dialysis.

Monitoring for Infectious Diseases

Pig kidney clinical trials present challenges in managing the risk of diseases that might be transmitted from pigs to humans. These diseases could infect not only the transplant recipients but also their close contacts (including members of their household and their intimate partners), the transplant team, and the public, which could have public health implications. Participants in a pig kidney clinical trial will need to undergo long-term and possibly lifelong monitoring for these diseases. However, a core principle of research ethics is that participants have a right to withdraw from research at any time. Thus, if participants in a pig kidney clinical trial decide to withdraw and decline to continue following monitoring requirements, they should be permitted to do so. If after withdrawing they exhibit symptoms associated with a porcine infection, then standard public health measures, including mandatory state reporting requirements of confirmed communicable diseases, can be implemented to address the situation.

We do not support mandatory monitoring of participants’ close contacts as a condition for patients to enroll in a pig kidney clinical trial. Clinical trial sponsors and researchers cannot compel individuals who are not enrolled in a clinical trial to agree to trial procedures. However, including close contacts in the informed consent process for clinical trial participants would provide an opportunity to inform the close contacts about monitoring requirements. Close contacts should be provided with written information that describes symptoms they should be aware of and whom to contact if they experience those symptoms.

Metrics for Evaluating Success

The success of xenotransplant clinical trials must be measured using conventional transplant metrics and new, xenotransplantation-specific metrics. They include evaluating graft function, surgical outcomes, and patient survival, as well as novel outcomes such as immune responses to porcine antigens and potential porcine transmitted infections. These metrics should be informed by input from diverse stakeholders to ensure that trial outcomes reflect the priorities of the affected communities. For example, clinical trial participants and their caregivers might identify additional outcome metrics for evaluating the success of a pig kidney clinical trial.

Pig kidney clinical trials require rigorous attention to ethical principles of justice, respect for persons, nonmaleficence, and beneficence. The path forward demands continued dialogue between researchers, patients, transplant teams, and policymakers to ensure that these groundbreaking trials serve the public interest while protecting participant welfare, preserving scientific integrity, and sustaining public trust.

Acknowledgment: This essay and the materials we developed were supported by an award (R01TR003844) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to Karen J. Maschke, PhD, The Hastings Center for Bioethics; Michael K. Gusmano, PhD, Lehigh University; and Elisa J. Gordon, PhD, MPH, Vanderbilt University Medical Center; multiple Principal Investigators. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCATS or NIH.

Karen J. Maschke, PhD, is a senior research scholar at The Hastings Center for Bioethics.

Michael K. Gusmano, PhD, is a professor in the Department of Community and Population Health in the College of Health at Lehigh University.

Elisa J. Gordon, PhD, MPH, is a professor in the Department of Surgery and the Center for Biomedical Ethics and Society at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.