Bioethics Forum Essay

Coronavirus and the Crisis of Trust

Every day, common bacteria and viruses like strep pneumoniae and influenza infect human lungs, making it difficult to breathe and, for some, impossible to live. In contrast to other infectious diseases, lower respiratory infections have persisted for decades among the top four global causes of death for adults and children of all income groups. So, what’s different about COVID-19? Maybe a lot–but maybe not so much.

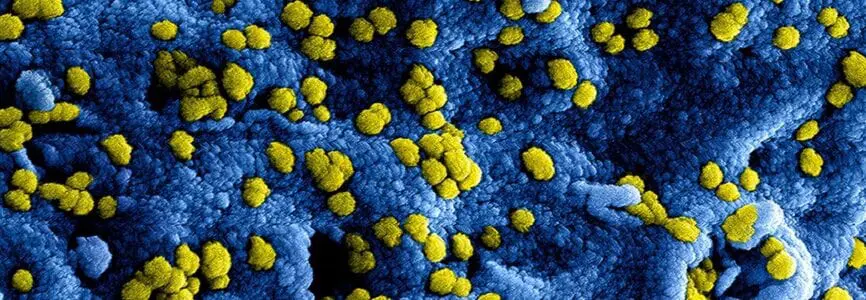

Influenza and coronavirus cause similar symptoms probably through similar modes of transmission. What is unique is that initial public health failures, including concealment, disinformation, and blatant mismanagement of testing and quarantine in China, Iran, the United States and other countries, enabled COVID-19 to travel in the direction of wealth undetected, hitching a ride along the hands and respiratory droplets of airline passengers around the world. The ensuing months of quarantines, misinformation, missteps, conspiracies, and cover-ups no doubt have left their mark on public trust: trust in our governments, trust in our public health systems, trust in our health care providers, and (with the uptick of outward racism) trust in our daily human interactions.

The primary culprits of COVID-19—institutional disinformation and concealment of information—have particularly eroded trust in international and government words and actions among the general public. To understand the ramifications of such violations of public and personal trust, let’s reflect on the Ebola crisis in West Africa (and remember that up until this week Ebola continued to plague the Democratic Republic of the Congo with a fatality rate of 60%). During and following the crisis, international health organizations and governments around the world delayed and then hurriedly invested millions of dollars in rapid deployment, treatment, and surveillance. The global community reacted to the Ebola crisis at a grave cost to the affected West African nations. Apart from the loss of human life, this toll included a severe disruption of health care services, decline in health care utilization and an increase in non-Ebola deaths that accounts for about $19 billion of the crisis’s estimated $53 billion cost.

What did not follow Ebola was investment in health care infrastructure other than for surveillance purposes, empowerment of providers with basic medical equipment, protective personal equipment and diagnostic resources, and trust-building in local and national health systems (with few exceptions). The resultant scarcity of intensive care in West Africa and much of the continent means African patients with severe COVID19 will suffer worse outcomes than their counterparts in high-income countries–a déjà vu moment recalling the discrepancy between Ebola’s mortality of 40-90% in West Africa versus 20% in Europe and the U.S. Even in high-income countries, hospitals have begun to encounter or anticipate overwhelming volumes and inadequate capacities that will be devastating in countries with less robust emergency systems.

Without addressing the root causes of such crises and the economic, health and social inequities of reaction over preparedness, COVD-19 and its crisis of trust will fade into the past, along with Ebola, swine flu, SARS, MERS, and even annually-amnesia-producing influenza virus. Without adequate preparation through emergency care capacity-building, primary and intensive care strengthening, and consistent communication, a pandemic of distrust will awaken on an increasingly regular basis in our increasingly globalized world.

What can we, those with freedom of expression in higher-resourced health care systems, do to build trust? We must insist on truth by publicly decrying and correcting disinformation and misinformation and rallying our elected representatives and communities to provide accurate information. We must rely on trustworthy sources, such as the websites of Johns Hopkins, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the World Health Organization. We must fight for emergency preparedness, including high-quality pre-hospital, emergency, and intensive care and capacity-building post-crisis, by protesting budget cuts to essential domestic and global health programs, emergency response funds (and strategic teams), and critical research. We must elect government representatives dedicated to improving emergency care systems globally.

Last fall, the Global Preparedness Board issued this ominous warning: “For too long, we have allowed a cycle of panic and neglect when it comes to pandemics: we ramp up efforts when there is a serious threat, then quickly forget about them when the threat subsides. It is well past time to act.”

Let’s work together to spread facts, not fear; tell reasons, not rumors; and create solidarity, not stigma. And most importantly, let’s remember to act – to be proactive — when this pandemic, like all others, subsides.

Alexandra Friedman is a fourth-year medical student at the University of California San Francisco who plans to specialize in emergency medicine. Twitter @shmalzi

For additional information and ethics resources on the Coronavirus, please visit our Ethics Resources page:

https://www.thehastingscenter.org/ethics-resources-on-the-coronavirus/