Bioethics Forum Essay

Bioethics Without Roe

The 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade has played a subtle but critical role in the history of bioethics in America. The finding of a constitutional right to abortion coincided with the first several years of a more or less self-conscious transition from traditional medical ethics, focused on physician decision-making, to “bioethics,” which incorporated the patient’s values and preferences. By the early 1980s informed consent was widely seen as the application of the principle of respect for autonomy.

Neither of the first two bioethics research centers, The Hastings Center (1969) and the Kennedy Institute (1971), had abortion explicitly on their agendas, but the prospects for control of the genetic traits of future human beings and the scope of parental decisions concerning seriously ill newborns were. Questions about the moral status of future and tiny humans were only one step removed from that of the moral status of the human embryo. In 1970 Hastings co-founder Dan Callahan, with the support of the Population Council, published a monograph, “Abortion: Law, Choice, and Morality.” In retrospect, in the 1970s and 1980s Roe enabled the growing field to put abortion per se on the back burner.

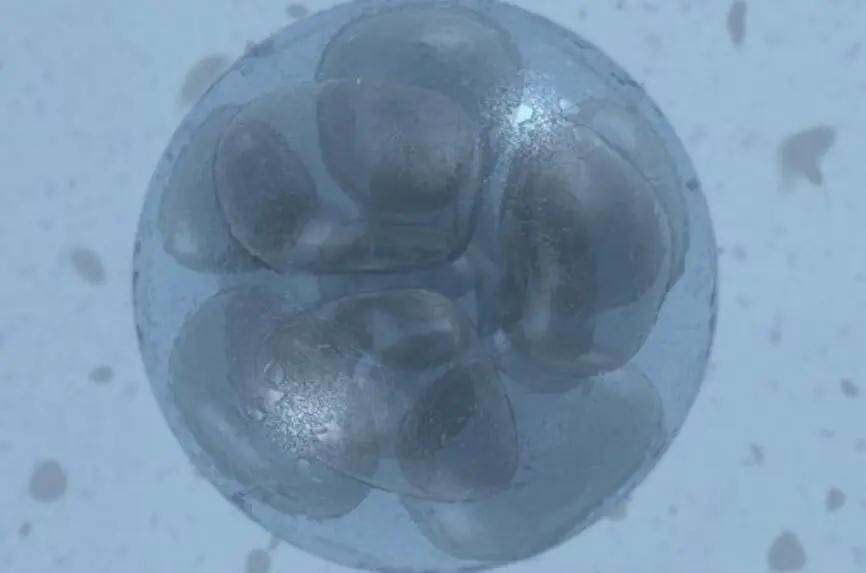

After the Quinlan decision (1976), in the public sphere the most pressing “life” issues came near its end rather than its beginning. The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research maintained its focus on human experiments after the revelations of the Tuskegee syphilis study, including those involving the human fetus, without needing to grapple with abortion. The surprise that accompanied the first successful in vitro fertilization in 1978 turned the matter of human reproduction on its head, emphasizing the ability of a technology to satisfy the deep and previously unfulfilled wishes of so many couples to produce a baby rather than to avoid doing so. Even here, though, a few social conservatives in the bioethics community quietly harbored deep reservations about technologically mediated human reproduction, though they would not be fully expressed for many years.

Not that abortion ever totally left the landscape. In the 1980s, Roe permitted bioethicists like Dan and Sidney Callahan and Baruch Brody and philosophers like Judith Jarvis Thompson to focus on ethical arguments about pregnancy termination that could be persuasive in personal decisions, given that the right to decide was the law of the land. Once again pro-life attitudes could be discerned in the background of issues that did not explicitly engage abortion, such as allegations about prejudicial management of certain newborns in the neonatal nursery and federal restrictions on the use of funds for fetal tissue research. These topics were in effect proxies for the underlying question about the moral status of the embryo. Despite technological advances the fact remained that the prospects for an artificial placenta that would thoroughly undermine the trimester framework established by Roe were thoroughly speculative, thus barely relevant to the conversation.

The 1992 decision in Casey replaced the trimester framework established in Roe, seen as potentially at risk due to technological advances in rescuing very low birthweight neonates, with the “undue burden” standard that restricted states’ ability to limit abortion rights. The intensification of the legal and political debate in the ensuing two decades, taking place in a society increasingly polarized along this and other lines, crept into bioethics as well. Again, though, the fact that Casey generally upheld abortion rights kept the pressure off. This state of affairs can now be seen as having gradually shifted with the achievement of mammalian cloning and especially with the isolation of human embryonic stem cells. Both lent momentum to long-simmering worries among those with conservative views about bioethics and what some have long seen as the dominant liberal slant in mainstream bioethics that had managed largely to set aside the question of the moral status of the embryo for so many years. President George W. Bush’s Bioethics Council under Leon Kass gave voice to what many of its members believed was the need for a “richer bioethics.”

Would American bioethics discourse be changed with the end of a constitutionally protected, even if highly restricted, right to abortion? In a field that takes as its mission the continuous reflection on moral values in human life and has in essence known no world without a constitutionally protected abortion right, one can hardly imagine it will not.

Jonathan D. Moreno is the David and Lyn Professor of Ethics at the University of Pennsylvania and a Hastings Center fellow. @pennprof

Thank you for your insights on the history of this question and how the question has been avoided — I’m curious how you think secularization will influence ethical thinking on the issue.

One of the curious facts about the way the abortion issue has unfolded is that as the country has become more secularized restrictions on abortion have intensified. I attribute this partly to a sense among pro-life advocates that in this secularizing environment it is all the more important to keep one’s foot on the gas, while those who consider themselves pro-choice have assumed that the overall direction of the society makes a threat to choice so much less plausible. Clearly that is not the case. Well-organized, persistent, focused, funded and patient advocacy makes a big difference in the US political system, as we have seen, even for minority views.