Bioethics Forum Essay

Benjamin Cardozo on Medicine and the Law: Wisdom for Senate Confirmation Hearings

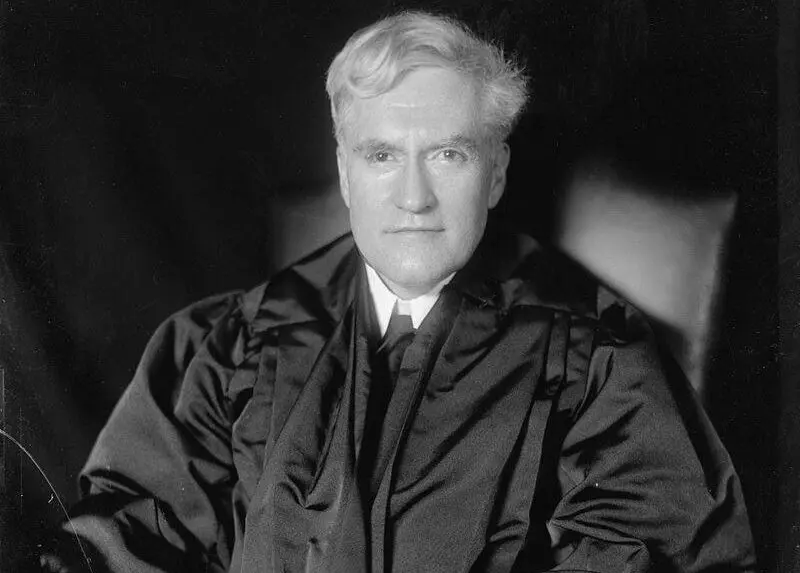

Back in 1928, Chief Judge of the New York State Court of Appeals Benjamin Cardozo presented the Anniversary Address to the New York Academy of Medicine. Cardozo, who would be appointed to the United States Supreme Court by President Roosevelt, presented an elegant talk entitled, “What Medicine Can Do for Law.” It is a contemplative ode to the two learned professions and their relationship to each other. It was the perfect setting for this conversation: a distinguished jurist speaking to an appreciative audience of doctors.

A different juxtaposition came to mind last week with the cabinet nominations for the Departments of Justice and Health and Human Services, each the modern embodiment of the two professions that Cardozo held in high esteem. In a flurry of activity, the incoming president placed candidates into nomination who seemed anachronistic and, less charitably, unworthy of the offices that they might hold.

Beyond policy disagreements or concerns about qualifications, there was something more foundational that bothered me about their nominations. Both seemed to violate a core ethos of Cardozo’s characterization of the two professions, each of which has sought to serve society since antiquity.

With a degree of veneration, Cardozo reminded his listeners of the common origins of the two professions in the priestly tradition. He began by asserting, “There are those that say that the earliest physician was the priest, just as the earliest judge was the ruler who uttered the divine command and was king and priest combined.” While he cautioned his physician audience “that modern scholarship warns us to swallow with a grain of salt these sweeping generalizations . . . they have at least a core of truth.” Invoking the deity in ancient times was a way to convey seriousness of purpose and authority bestowed by the gods. Those so chosen were worthy of the responsibility and up to the obligations of their tasks.

Cardozo acknowledged that medicine and the law have sometimes been seen as being in opposition, but he stressed their common roots and connections with the divine mysteries of life. He observed, “Our professions — yours and mine — medicine and law — have divided with the years, yet they were not far apart at the beginning. There hovered over each the nimbus of a tutelage that was supernatural, if not divine. To this day each retains for the other a trace of the thaumaturgic quality distinctive of its origin.”

Thaumaturgic is an interesting word deriving from the Greek. It is often associated with magical abilities to alter the natural world: the physician who confronts disease and the judge who has powers beyond his peers. Each of these magical powers has persisted to modernity. “The physician is still the wonder-worker, the soothsayer, to whose reading of the entrails we resort when hard beset,” Cardozo said. “We may scoff at him in health, but we send for him in pain.” Similarly, “The judge, if you fall into his clutches, is still the Themis of the Greeks, announcing mystic dooms.” In Greek mythology, Themis is the divine personification of justice.

With these allusions, Cardozo singles out medicine and the law from other forms of human endeavor. Each has extraordinary powers, and both are shrouded in mystery that resides deep within the traditions and history of these two essential professions. As Cardozo reminded us of physicians and judges, “You may not understand his words, but their effects you can be made to feel. Each of us is thus a man of mystery to the other, a power to be propitiated in proportion to the element within it that is mystic or unknown.”

It is this mystery, those traditions, that deserve reverence and respect when it comes to the president-elect’s nominations for the heads of the Departments of Health and Human Services and of Justice. For medicine, it is falsifiability and the scientific method. For the law, it is stare decisis, the importance of the stability of the law in civil society. For both medicine and the law, it is the ability to distinguish fact from fiction, whether it is evidence in a clinical trial or what emerges in a court of law. These are the enduring features of these two professions — methods and epistemologies — that demand deference and respect from those who would seek to lead these important departments.

Medicine and the law have, as Cardozo noted, been civilizing forces throughout history. Too much is at stake to deconstruct what took millennia to evolve. Probity demands careful scrutiny of those entrusted with these roles during Senate confirmation hearings. This prescription holds true even with the withdrawal of the president-elect’s first nominee for attorney general. It is a recommendation that must endure for future candidates for this office. Nominees may change but the norms articulated so eloquently by Cardozo must endure.

No one less than Justice Benjamin Cardozo reminds us of the solemnity of these posts. Life and death, progress or regression, hang in the balance. Hopefully Cardozo’s words from nearly a century ago will echo in the corridors of power today.

Joseph J. Fins, M.D., D. Hum. Litt. (hc), M.A.C.P., F.R.C.P., is the E. William Davis Jr. M.D. Professor of Medical Ethics, a professor of medicine and chief of the division of medical ethics at Weill Cornell Medical College; Solomon Center Distinguished Scholar in Medicine, Bioethics and the Law and a Visiting Professor of Law at Yale Law School; and a member of the adjunct faculty at the Rockefeller University. He is a Hastings Center fellow and chair of the Center’s board of trustees. At the dawn of the current U.S. president’s administration he wrote an essay, “Science in the Biden White House: Eric Lander, Alondra Nelson and the Legacy of Lewis Thomas” for Hastings Bioethics Forum.

This article was very illuminating. I contend that the medical field would greatly benefit from adopting the wisdom found in our legal system by implementing appropriate safeguards within the evolving evidence-based practice models.

Such safeguards could help prevent the unchecked influence of biased or selective scientific advocacy, which often jeopardizes the interests and well-being of patients.

Learning from the Legal System: Implementing Safeguards in Evidence-Based Practice to Prevent Unbounded Scientific Advocacy

Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) in healthcare aims to provide scientifically grounded, standardized methods for clinical decision-making. However, in its application, EBP has unintentionally transformed healthcare professionals into advocates for specific treatment approaches, much like lawyers presenting cases in court. Clinicians are tasked with reviewing extensive bodies of literature, interpreting evidence, and championing what they believe is the best course of action for patients. While EBP was designed to improve patient care by using the best available evidence, it has also created significant challenges, particularly the rise of unbounded scientific advocacy. This occurs when clinicians, in their efforts to provide “evidence-based” care, selectively use literature to support their preferred methods, often disregarding alternative evidence or treatment approaches. Without the objective framework that the legal system provides through judicial oversight, precedent, and stare decisis, healthcare decisions are increasingly shaped by subjective interpretation, leaving patients vulnerable to biased or incomplete information. The EBP model could benefit from adopting safeguards from the legal system to seek to ensure that the best evidence has been identified without the influence of personal or professional biases, thereby protecting both the autonomy and ethical rights of patients.