Bioethics Forum Essay

Against Personal Ventilator Reallocation

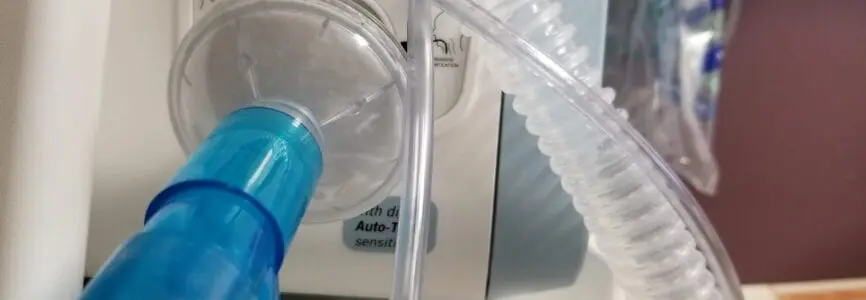

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to intense conversations about ventilator allocation and reallocation during a crisis standard of care. The ethical value of maximizing lives saved in a pandemic has received widespread support from clinicians and bioethicists for years, so much so that some consider it a fundamental tenet of public health ethics. During the Covid-19 pandemic, however, approaches that prioritize maximization of life have received repeated and notable challenges (see here, here, and here). One reason for such pushback is the implication that patients who could benefit from a ventilator might have the ventilator withheld or withdrawn if triage officers/teams decide that more patients could be saved by taking it from them. This reasoning could extend to ventilators outside the hospital setting; if more lives could be saved by taking advantage of chronic-use ventilators in the community, then it would follow that these ventilators should be part of allocation schemas.

This is not a mere academic point. The Food and Drug Administration issued guidance for modifying home- and facility-use ventilators as needed for the Covid-19 pandemic. In New York, the federal government continually refused to provide needed support and the pandemic overwhelmed hospitals so severely that Governor Cuomo authorized the National Guard to take control of excess community ventilators, announcing his plan in an April briefing that caused some alarm. As another example, multiple hospitals approached a nursing home on Long Island, requesting access to unused ventilators; the first hospital to make the request received 11 ventilators, leaving the facility with only 5 on hand for current and future residents. Even outside of New York, health care systems globally are having to find ways to increase supplies and plan for a crisis standard of care. The possibility of personal ventilator reallocation is a serious concern in the disability community, and as the pandemic continues to unfold, bias against persons with disabilities remains a perpetual source of tension and distrust.

Bioethicists, health care professionals, and public agencies must pay attention to this concern and clarify promptly: Are personal ventilators part of the reallocation pool during a pandemic like Covid-19, or not? What are the primary ethical question that underlies such a decision: should they be or not?

In our forthcoming piece in Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, we argue that personal ventilators should not be part of reallocation pools and that triage protocols should be immediately clarified and explicitly state that personal ventilators will be protected in all cases. First, there is an urgent moral need for explicit policies concerning ventilator reallocation at institutional, state, and federal levels. Second, personal ventilator reallocation raises crucial symbolic issues concerning the historically fraught relationship between the norms of biomedical and public health practices and the needs and well-being of the larger disability community.

Through an analysis of phenomenological, neuroscientific, ethical, and socio-political considerations pertaining to the experience of long-term ventilator users, we argue that ventilators should be considered as an integrated technology: a technology that is essential to one’s functioning across the life course and part of one’s social identity. Furthermore, integrated technologies such as ventilators are powerful symbols concerning the worth of disabled people’s lives amidst this political and existential crisis. In sum, personal ventilator reallocation should be banned in all cases. State, federal and insitutional policies should make such a ban explicit immediately.

Joel Michael Reynolds, PhD, is an assistant professor of philosophy and disability studies at Georgetown University and was The Hastings Center’s inaugural Rice Family Fellow in Bioethics and the Humanities. @joelmreynolds. Laura Guidry-Grimes, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Medical Humanities and Bioethics at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, and she works as a clinical ethicist at UAMS Hospital and Arkansas Children’s. She contributed to The Hasting Center’s new ethical framework and educational resources on responding to COVID-19. @GuidryGrimes. Katie Savin, MSW, is a PhD candidate in the School of Social Welfare at the University of California, Berkeley. She participates in The Hastings Center’s working group on dementia and the ethics of choosing when to die. @Ksavin.

This piece is adapted from the following forthcoming article: Joel Michael Reynolds, Laura Guidry-Grimes, and Katie Savin, “Against Personal Ventilator Reallocation,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. An early version of these arguments appears in : Laura Guidry-Grimes and Katie Savin, “‘Will They Take My Vent?’: Ethical Considerations with Personal Ventilator Reallocation During COVID-19,” in Bioethics.net.

45% of The Hastings Center’s work is supported by individual donors like you. Support our work.

Ventilator rationing and reallocation is already happening – it’s just happening in more complex and ways based on supply chain dysfunction.

A ventilator isn’t just a $40,000 life support machine – it’s also a set of disposable filters and circuits that connect the ventilator to the patient. A ventilator without circuits and filters is a $40,000 paperweight.

The entire supply chain of filters and circuits – which are entirely necessary for ventilators to function and for ventilator users to live – has been rerouted to acute care hospitals for COVID patients.

Ventilator rationing isn’t just the dramatic decision of a doctor to redistribute a ventilator from one patient to another, which is obviously murder. Ventilator rationing is the delivery system that has home ventilator patients washing and reusing sterile, disposable equipment in the kitchen sink, duct taping their circuits together, and contaminating the interns parts of their ventilators with mold because filters are essentially unobtainable for anyone outside of an acute care hospital right now.

My nine year old son is a ventilator user. We’re currently getting supplies, but only because our home equipment provider is wholly owned by a hospital and has access to their purchasing contracts. The majority of home ventilator users are facing hard rationing of sterile, disposable equipment, and many home ventilator companies have simply stopped providing the supplies they can’t obtain.

Ventilator rationing isn’t theoretical. It’s happening here, it’s happening now, but it’s happening at a more complex level than the triage / crisis of care decision process.

I’ve been compiling anecdotes from the online ventilator community, and I got a state level article written, but I haven’t been able to get any policy traction on this issue.