Bioethics Forum Essay

A Model of Conscientious Objection to Abortion Bans

With the fall of Roe v. Wade a year ago, many states have passed laws criminalizing abortion in full or in part, making it difficult or impossible for health care providers to give proper care for the people whom they are supposed to serve. This dramatic turn of events is not new; it merely exacerbates a trend that has been growing for some time. For decades, several states have required clinicians who perform abortions to give inaccurate medical information to patients, a clear violation of basic medical ethics and standards of care. Many clinicians have followed their conscience to find ways to provide good care within the confines of these mandates.

Conscientious objection goes both ways, as Kimberly Mutcherson pointed out recently at the Hastings Center Fellows annual meeting. We are used to thinking of health care providers who refuse on grounds of conscience to participate in aspects of medical care. But conscientious objection can also be the act of insisting on providing care. Margaret Sanger and others did this in the days when providing contraceptives was illegal. We owe the groundbreaking case of Griswold v. Connecticut, which upheld the right of married couples to use contraceptives, to Dr. C. Lee Buxton, professor at Yale Medical School, who risked arrest, fines, and damage to his career by providing contraceptives in defiance of the law.

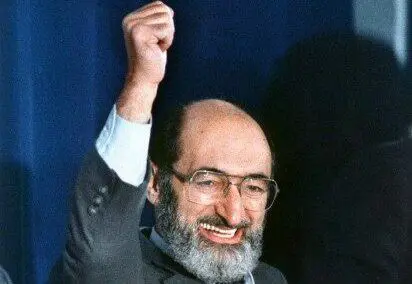

Less well known for practicing medicine conscientiously in defiance of the law is Henry Morgentaler. Morgentaler (above) was a Polish Jew who born in Lodz in 1923. His father was murdered by Nazis soon after the German invasion of Poland. Henry’s older sister had moved to Warsaw, where she and her husband were killed fighting in the Warsaw ghetto uprising. The rest of the family was incarcerated in the Lodz ghetto. When the ghetto itself was raided, 19-year-old Henry hid with his brother and mother. They were discovered after two days; their mother died in Auschwitz. The brothers were shipped to Dachau. When Henry and his brother were liberated in 1945, Henry weighed 71 pounds.

After the war, Henry settled in Québec, earning his medical degree in 1953. Considering the horrors of his early life, one might have expected Henry to settle gratefully into a placid existence, practicing family medicine without making waves. However, in 1967, he stated publicly that women should have the right to abortion, when was then illegal in Canada. He began to receive increasingly desperate calls from women needing to end their pregnancies. He tried at first to refuse, or to refer them elsewhere, but soon the “avalanche” of requests overwhelmed him. He knew that women were dying from illegal abortions, and he felt “like a coward” for turning his back. He determined to help women and to challenge the law at the same time.

Morgentaler gave up his family practice and in 1969 he opened a clinic that provided abortions and contraceptives (also illegal at the time). He was tried three times between 1973 and 1975 for defying the anti-abortion law; each time he pleaded the defense of necessity and brought as witnesses some of the women he had helped. (In Anglo-American law, the necessity defense is invoked when the illegal behavior was necessary to avoid a larger harm, for example if one had stolen a car as the only way to rush a dying person to hospital.) Each time the jury refused to convict him. Finally, the Québec Court of Appeal overturned the jury verdict and sentenced Morgentaler to jail. He was in prison for 10 months and suffered a heart attack while in solitary confinement. (In 1975, the Canadian Parliament changed the law so that an appellate court could not overturn a jury verdict.)

Again, one could have expected Morgentaler to hand the torch to others. However, for the next 15 years he opened abortion clinics across Canada, challenging the laws in different provinces. In 1983 he was arrested again, this time in Toronto, where he again used the defense of necessity and was acquitted by the jury. The government appealed and his case reached the Supreme Court of Canada. In 1988 that court ruled that the restrictive abortion laws violated Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Morgentaler was forced to stop performing abortions after heart surgery in 2006, but he continued to oversee six clinics. In 2009, only four years before his death at age 93, he was working to open two private abortion clinics in the Canadian Arctic, to bring reproductive health to women who would otherwise have to travel huge distances. Among his many honors was the “Maggie Award,” from the Planned Parenthood Federation, named in tribute to Margaret Sanger. He was named a member of the Order of Canada in 2008.

The model of a towering hero such as Morgentaler can be overwhelming to us ordinary mortals. We think, “He’s a hundred times braver than I am,” and the gulf between us and him seems so huge that the default is to do nothing at all. Yet conscientious objection is something that an increasing number of us, laypeople and clinicians alike, are confronting. Texas has turned everyone into a potential bounty hunter, with the possibility of severe civil penalties to anyone who drives someone to an abortion clinic, lends a friend money, or babysits for her kids while she seeks an abortion. The Texas law and others like it include people outside the health profession in the challenge of how far we are willing to go to help women access reproductive care. But if a hundred of us are each a hundredth as brave as Morgentaler, imagine what we could accomplish.

Dena S. Davis, JD, PhD, is the endowed presidential chair in health and a professor of bioethics and religion studies at Lehigh University and a Hastings Center fellow.

Many, many thanks for this commentary/essay. I will use this in my Morals and Medicine course…VERY much appreciate this history (which I did not know)….

Thanks. I only knew about him because I lived in Montreal in the 1970s.

A great story and well-told. Thanks!

Morgentaler was a truly brave trailblazer for women’s rights, beginning his challenge over 50 years ago. He challenged Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which protects everyone’s right to life, liberty and security of the person. This protects personal autonomy and bodily integrity from laws or actions by a government that violates those rights. As a Canadian who studied bioethics in Toronto, I find it deeply disheartening these basic human rights are not afforded to all Americans, despite their gender. I fear for the health and safety of American women seeking control over their own reproductive health.

Also, for further reading, I recommend “Doctors of Conscience: The Struggle to Provide Abortion Before and After Roe v. Wade” (Beacon Press, 1996) by Carole E. Joffe.