Bioethics Forum Essay

Newly Released Documents from Untreated Syphilis Study: Ethical, Just, and Respectful Use of Archival Materials

To mark the 50th anniversary of the end of the United States Public Health Service’s Syphilis Study, the National Library of Medicine recently digitized and released reams of historical documents on the “origin and development of the Tuskegee syphilis study,” including journals, newspaper articles, personal correspondence, and other records. The release of these documents is a poignant occasion to consider what qualifies as ethical, just, and respectful use of archival materials.

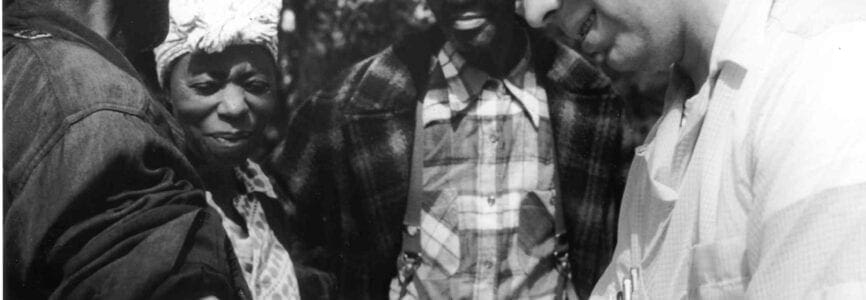

The United States Public Health Service was responsible for conducting a 40-year study (1932-1972) designed to document the natural history of untreated syphilis among Black men from Macon County, Alabama. This notorious study systematically targeted a medically and economically disenfranchised population, provided misleading and false information about the study’s procedures and intent, and deliberately withheld treatment after penicillin became the widely available standard of care for syphilis.

The Syphilis Study Legacy Committee was established in 1994 to elicit a formal apology from President Bill Clinton in recognition of the atrocities of this government-funded study and to develop a strategy to understand and address the long-term impact of the study on Black Americans. The work of the Legacy Committee led to the establishment of the National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care at Tuskegee University, whose founding director was the late Marian Gray Secundy. Secundy’s personal legacies, as a passionate advocate for health equity, a visionary scholar, and an exemplary mentor and collaborator, have been the subject of recent focused work in bioethics to reintroduce her work to the next generation of scholars and advocates.

Medical historian, physician, and bioethicist Vanessa Northington Gamble chaired the Legacy Committee. In a classic 1997 essay, “Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care,” Gamble called attention to the invocation of “Tuskegee” to represent “racism in medicine, misconduct in human research, the arrogance of physicians, and government abuse of Black people.” To rightfully emphasize the histories of medical racism in the U.S. Gamble and other scholars have long cautioned against attributing distrust in the health care system by Black Americans mainly or solely to the betrayal experienced by the men enrolled in the USPHS study. We argue that utterances of “Tuskegee” convey a misleading shorthand—an untidy explanation for medical mistrust of the health care system among Black Americans. Simply put, it is the institutions of health care delivery––then and regrettably now––that perpetuate mistrust.

Now is the time to reframe this narrative. We can acknowledge the deep symbolism of the USPHS Syphilis Study concerning the long and continuing trajectory of abusive practices in research and health care, while reconceptualize how we think about, teach about, and pass along the legacy of “Tuskegee.” This rethinking of scholarly and public-facing discourses requires the inclusion of community-level perspectives and concerns. In recent years, Macon County leaders and advocates have called attention to the mischaracterization and misnaming of the USPHS Syphilis Study. Lillie Tyson Head, President of the Voices for Our Fathers Legacy Foundation, highlights the ongoing local, cultural, and societal harms of invoking “Tuskegee.” Head states, “When you place Tuskegee in front of the name, it gives Tuskegee the ownership, it leaves a scar on the town of Tuskegee and of Macon County. Tuskegee was not, is not, the owner of the study. It is the United States Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male at Tuskegee.”

The recent release of documents related to the study is an opportunity to consider what qualifies as ethical and respectful use of sensitive historical materials. It is also an opportunity, even a duty, for bioethics and medical and health humanities scholars, whose fields have been shaped in part by the need to learn from injustices in research and health care, to respond to this moment, in collaboration with historians, archivists, curators, and community members.

As bioethics and medical and health humanities scholars, we offer some initial insights and questions regarding the use and dissemination of this digital archive. How should the perspectives of community members inform the preservation, interpretation, and presentation of these documents? Will people with interdisciplinary expertise (e.g., those with lived experience, medical historians, museum curators) be engaged in the archival work? Who benefits from and who is potentially harmed by making these historical documents publicly available? How can potential harms be prevented, or the risk of harm reduced? What does it look like to recognize the full humanity of everyone involved in the USPHS Untreated Syphilis Study? How should these documents and their recontextualization of the continuing struggle for racial health justice and for trustworthiness in health care and research be used to best inform public bioethics and public humanities work? For example, public bioethics work related to this public archive could include outreach to health journalists with the goal of supporting a more robust and context-specific understanding of these materials to inform ethically grounded research and health care practices.

While approaches to representing the USPHS Untreated Syphilis Study archives will vary by discipline, we suggest that all scholars, educators, and others working with these materials remember, honor, and recognize the lives and legacies represented by these documents particularly the men, families, and local communities victimized by the study. To demonstrate trustworthiness, respect, and transparency as ethical stewards of these archival data, bioethicists and medical and health humanities scholars must lead this charge.

Faith E. Fletcher, PhD, MA, is an assistant professor in the Center for Medical Ethics at Baylor College of Medicine, a senior bioethics advisor to The Hastings Center and a Hastings Center fellow of The Hastings Center. @FaithEFletcher

Sophie L. Schott, BA, is a clinical research coordinator in the Center for Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Baylor College of Medicine. @MyBestSchott

Virginia Brown, PhD, MA is a research scholar in Health Equity and Population Health at The Hastings Center. @VirginiaABrown

Nancy Berlinger, PhD, is a senior research scholar at The Hastings Center, where she directs the Sadler Scholars initiative for doctoral and early-career researchers from racially minoritized communities.

Stephen O. Sodeke, PhD, DBE, is resident bioethicist at the Center for Biomedical Research, Professor of Bioethics and Allied Health Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, Tuskegee University.

Thank you to the Legacy Committee for bringing these additional materials forward. They will undoubtedly further inform our understanding of the tragedy which was the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. But as we look forward to learning more about this pivotal chapter in modern bioethics, let us note that none of this would be possible had there not been these archival resources. Archives are the repository of history and must be preserved and sustained in the academy. Resources for archives are often under threat in library and university budgets but are essential fonts of scholarship. Truly, the archive is to the historian (or biographer) what the laboratory is for the bench scientist. Archival research, like science is exhausting but the results can be transformative. Discoveries can exist on the very next page, if there are pages to turn. Here I think of how Susan Reverby’s inquiry into the University of Pittsburg archives of USPHS physician John Cutler revealed the atrocities committed in Guatemalan in parallel to the Tuskegee study. This was wholly unexpected and a discovery which led President Obama’s Bioethics Commission to author their extraordinary report, “Ethically Impossible: STD Research in Guatemala from 1946-1948.” This research revealed that we only knew part of the story, a story which had entered the bioethics canon as if complete before Reverby’s revelations. History is always incomplete and we should be as attentive to the contingency of historic information as we are about scientific discovery. And as we reflect on the unfolding of new knowledge, we have to appreciate that none of this would have come to light without a committed historian and a preserved archive for her to examine. So as we look forward to learning more about Tuskegee let us remember that the only history we know is that which is discovered and that these materials need to be curated and preserved by skilled archivists. Their whose work often goes unrecognized, unheralded and underfunded. Along with historians, they too are the heroes and heroines of this story.

Thank you for your thoughtful comment! In this piece, we link to the Tuskegee Legacy Museum. Cynthia Wilson is a veteran archivist and worked with scholars like Susan Reverby. As a collective, we are working to acknowledge, support and amplify those who make this work possible. It starts with funding and hope people consider supporting HBCU archives to carry forth this work in a meaningful and respectful way: https://www.tuskegee.edu/libraries/legacy-museum