Ethics and Aging

Selected resources from The Hastings Center.

Bioethics Briefings:

Aging

There is a steady rise in world population growth with the fastest proportional increase coming from the elderly. Technological advances in medicine allow the elderly to live longer but with increasingly higher medical costs and difficult dilemmas in end-of-life care. As people live longer, they also risk financial insecurity. Read our briefing to consider: What are the ethical and policy issues in an aging society?

From Hastings Bioethics Forum:

- This Wasn’t the Plan: A Family Caregiver’s Recommended Readings from 2023Work and life overlapped significantly for me in 2023. The timeframe for the latest project in the Bioethics for Aging…

- The Place in “Aging in Place”: Housing Equity in Late LifeMost older Americans want to age “in place” – in the community, not an institution. But there’s a poor fit between our nation’s housing stock and our aging demographics.

- Housing an Aging Society: Five PrioritiesWhile home and neighborhood environments matter to all people, older age brings particular considerations related to housing cost, safety and…

- Individuals Declared Brain-Dead Remain Biologically AliveA remarkable experiment raises anew questions about whether brain-death is really death.

- Why I Don’t Support Age-Related Rationing During the Covid PandemicSome bioethicists support age-related rationing of ventilators during the Covid-19 pandemic as a way to save the most lives. But that goal might be better realized without strict age cutoffs.

- A Covid-19 Side Effect: Virulent Resurgence of AgeismOf all the “isms,” ageism is arguably the hardest to address because old age neither a valued stage of life nor an identity that many claim. The coronavirus pandemic may have made that effort even harder.

- On Being an Elder in a PandemicDo the elderly have special obligations during a pandemic, that is, something more than the duty we all have for hand washing, social distancing, and so on? I believe the answer is, yes, and foremost among these is an obligation for parsimonious use of newly scarce and expensive health care resources.

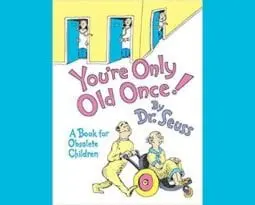

- What Dr. Seuss Saw at the Golden Years Clinic“Improving patient experience” has become the mantra of many health care facilities in a highly competitive and regulated environment. But…

- A Single-Payer Bubble?In an earlier piece, “Trumping Drug Costs,” I looked at out-of-pocket costs as the pivotal issue with drugs. They can…

- Palliative Care vs. Cancer ResearchThe death of former first lady Barbara Bush at age 92 was noteworthy in many ways. She was by all…

- Is Death in Trouble?Death is beginning to show its age, though I hesitate to even mention that possibility. With an obviously big ego…

From Hastings Center Report:

Burdening Others

First published: 13 October 2022

Abstract

Many people are afraid they will, as they age or fall ill, become burdens to others. Some who fear this say they would be willing to hasten their own deaths—engaging in self-sacrifice through suicide, assisted suicide, or euthanasia—to avoid it. Still, some bioethicists and other critics of medical aid in dying reject the idea that fear of being a burden can be a good reason for self-sacrifice. They argue that dependency is nearly universal, emphasize that caregiving is a valuable pursuit, and raise concerns about the impact of aid-in-dying policies on vulnerable groups. After defining what it is to be a burden, articulating why being a burden is morally significant, and, crucially, distinguishing burdensomeness from what I call “mere dependency,” I defend the intuition that self-sacrifice can be justified by the desire to avoid being a burden and by the concern for the well-being of one’s caregivers that this choice implies.

When Is Age Choosing Ageist Discrimination?

First published: 15 December 2020

Abstract

When the Covid-19 pandemic reached the United States in spring 2020, many states and hospitals announced crisis standards of care plans that used age as a categorical exclusion criterion. Such age choosing was quickly flagged as discriminatory, and so some states and hospitals shifted to embedding age as a tiebreaker deeper in their plans. Different rationales were given for using age as a tiebreaker: that younger patients were more likely to survive than older patients, that saving younger patients would save more life years, and that younger patients deserved a chance to live through life’s stages. We provide a critical analysis of these three rationales, noting the differences between them, and then questioning the ethical and legal justifications for such age choosing.

OK, Boomer, MD: The Rights of Aging Physicians and the Health of Our Communities

First published: 14 December 2020

Abstract

How do we balance the rights of aging physicians against the right of the public to competent health care? This version of a classic public health ethics dilemma is here now and likely to increase as the population ages. Peer review has long been the standard mechanism for assessing physician competence, but it is subjective and too easily subverted. New options are needed, both in medicine and throughout the professions, but they are challenging to implement. Physicians have an ethical obligation to protect the health of the public by acknowledging, assessing, and addressing the cognitive effects of aging on medical competence.

Older Adults and Covid-19: The Most Vulnerable, the Hardest Hit

First published: 29 June 2020

Abstract

Older adults in the United States have been the age group hardest hit by the Covid pandemic. They have suffered a disproportionate number of deaths; Covid patients eighty years or older on ventilators had fatality rates higher than 90 percent. How could we have better protected older adults? Both the popular press and government entities blamed nursing homes, labeling them “snake pits” and imposing harsh fines and arduous new regulations. We argue that this approach is unlikely to improve protections for older adults. Rather than focusing exclusively on acute and critical resources, including ventilators, a plan that respected the best interests of older adults would have also supported nursing homes, a critical part of the health care system. Better access to protective equipment for staff members, early testing of staff members and patients, and enhanced means of communication with families were what was needed. These preventive measures would have offered greater benefit to the oldest members of our population than the exclusive focus on acute care.

How Long a Life Is Enough Life?

First published: 27 July 2017

Abstract

Humans have long been troubled by the prospect of old age and its culmination in death. Whether to rebel against or accept this fate have been wrestled with down through the centuries. But new medical technologies and the growing science of aging have sided with rebellion. We know that aging can be pushed back and improved in its quality. That progress is well under way, but now intensified by many scientists and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs. In 2016, Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan pledged three billion dollars toward eventually “preventing, curing or managing all diseases.” And some visionaries have made the elimination of death or its indefinite postponement a goal. To put those aspirations in a broader context, it is helpful to keep in mind where population growth and aging trends stand. Apart from any success in the explicit efforts to increase longevity, there will be a steady increase in the number of elderly worldwide—and a much higher percentage of the elderly as part of the overall population. Most of the largest changes will be in developing countries. They will be overburdened by the death of the elderly from expensive chronic diseases—already a vexing problem for affluent countries.

First published: July 2009

Abstract

Up until recently, most people died quickly and too soon. Now, with many illnesses curable or held at bay, many die very slowly and too late—sometimes many years too late. It’s time to rethink dying.

Special Reports

What Makes a Good Life in Late Life? Citizenship and Justice in Aging Societies

Hastings Center Report: Vol 48, No S3.

The ethical dimensions of an aging society are larger than the experience of chronic illness, the moral concerns of health care professionals, or the allocation of health care resources. What, then, is the role of bioethics in an aging society, beyond calling attention to these problems? Once we’ve agreed that aging is morally important and that population-level aging across wealthy nations raises ethical concerns that cannot be fixed through transhumanism or other appeals to transcend aging and mortality through technology, what is our field’s contribution? This special issue addresses how bioethics may to turn toward social justice to help facilitate a concept of good citizenship in an aging society that goes beyond health care relationships.

From The Hastings Center Bioethics Timeline

1965: Congress Passes Medicaid and Medicare

Despite opposition from the American Medical Association, two governmental health insurance programs are passed: Medicaid, which insures the indigent, and Medicare, which insures those 65 and older. The implementation of Medicare, along with the 1963 Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals case mandating desegregation of hospitals and linking desegregation with federal funding policies, transformed hospitals from among the most segregated to the most integrated institutions in the nation. The National Medical Association, which represents the interests of African American patients and physicians, supported both Medicaid and Medicare.

1967: Founding of St. Christopher’s Hospice in London

Cicely Saunders founds St. Christopher’s Hospice in London. As a nurse by profession, she focused on effective pain management and insisting that dying people needed dignity, compassion, and respect, as well as rigorous scientific methodology in the testing of treatments. She also believed that it was acceptable and even desirable to be honest with patients about their prognosis.

1969: Publication of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross’ On Death and Dying

Inspired by her work with terminally ill patients and motivated by the lack of instruction in medical schools on the subject of death and dying, Kübler-Ross examined death and those faced with it. She described the stages of grief as: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Kubler-Ross, E., On Death and Dying (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1969).

1974: First Hospice in the United States Founded

Florence Wald, former Dean of the Yale School of Nursing, founds the first hospice in the United States—the Connecticut Hospice in Branford, Connecticut—marking the beginning of the palliative care movement in the United States.

1976: “Orders Not to Resuscitate”

Two Harvard-affiliated teaching hospitals publish their policies on nonresuscitation decisions in a 1976 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, initiating public discussion of the ethical issues surrounding these decisions.

https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM197608122950705

1981: Right to Refuse Life Sustaining Treatment Upheld by New York Courts

In the Matter of Philip K. Eichner, On Behalf of Joseph C. Fox, Respondent, v. Denis Dillon. Brother Joseph Fox, an 83-year-old member of a Roman Catholic religious order, suffered a cardiac arrest and was placed on a ventilator, sustaining him in a permanent vegetative state. A fellow of his religious order, Father Eichner, sought appointment as Brother Fox’s legal guardian to act on Brother Fox’s express statement that were he in a situation like Karen Ann Quinlan, he would have ventilator support discontinued. The Supreme Court of New York held that Brother Fox had a common-law right to decline treatment and that wishes, expressed prior to becoming incompetent, should be honored. In 1981, the New York Court of Appeals upheld this ruling, declaring that a patient’s right should not be lost when a patient becomes incompetent.

https://www.leagle.com/decision/198141552ny2d3631383

1983: Publication ofDeciding to Forego Life-Sustaining Treatment

This report by The President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research integrated the bioethical paradigm of shared physician-patient decision-making into the daily routine of American health care, extending this model to end-of-life decision-making. To facilitate adoption of their recommendations, they published model durable powers of attorney, and similar documents relating to issues in end-of-life decision-making that were soon widely adopted and used.

1987: Publication of The Hastings Center’s Guidelines on the Termination of Life-Sustaining Treatment and the Care of the Dying

This publication was the first comprehensive consensus-based ethics guidance on end-of-life care. It provided guidelines for health care professionals on the decisions faced by dying patients, their families, and other caregivers. In the introduction to the second edition, the authors reflected on the first edition: “This groundbreaking book, whose principal author was Susan M. Wolf, was widely consulted and influential in the U.S. and internationally. It was cited by Justice O’Connor in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Cruzan decision and helped shape the current ethical and legal framework for medical decision-making and end-of-life care.”

Berlinger, N., Jennings, B., and Wolf, S. M., 2nd ed., The Hastings Center Guidelines for Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment and Care Near the End of Life (Oxford University Press, 2013). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2324200

1987: Publication of Daniel Callahan’s Setting Limits: Medical Goals in an Aging Society

This publication presents an influential and controversial discussion of the health needs of the aging and of health care rationing. Callahan brought to task the U.S. health care system for its emphasis on technological prolongation of life at the cost of quality of life, which would result in disproportionate societal resource allocation on extension of life. He called for focusing technological advancements and health care provision on the aim of quality of life for the elderly rather than quantity.

D. Callahan, Setting Limits: Medical Goals in an Aging Society. (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987). https://www.amazon.com/Setting-Limits-Medical-Society-Response/dp/0878405720

1990: Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990

Spurred by the Cruzan case, Congress passes the Patient Self-Determination Act, requiring health care institutions to provide information about advance health care directives to adult patients upon their admission to the healthcare facility. Advance directives initially had little effect on end-of-life care, but later studies would show that patients with advance directives would be more likely to have their wishes respected. The Act encourages adults who tend not to complete advance directives to do so.

Patient Self-Determination Act, Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, P.L. 101-508, Nov. 5, 1990. Effective, Dec. 1, 1991.

1990: Decisions near the End-of-Life Initiative

Medical education and practice change program led by Mildred Solomon, EdD and Bruce Jennings, MA that surveyed practicing clinicians, and informed by those findings, took bioethics into the field—reaching 40,000 providers in 237 health care institutions in 20 states from 1990 to 1996 and, through media coverage, the larger public as well. It was offered by the Education Development Center (EDC) of Newton, MA, in cooperation with The Hastings Center, the American Medical Association, the American Hospital Association, and the American Bar Association. Its work would reach end-of-life care across the United States, and would engender and inform subsequent programs such as the American Medical Association’s Education for Physicians on End-of-Life Care (EPEC) project (1998-present), a train-the-trainer program led by Linda Emanuel, MD, PhD, and subsequently by Joshua Hauser MD, now renamed the Education on Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) Program offered through Northwestern University that would reach thousands of trainers, and in turn, hundreds of thousands of health care providers.

Solomon, M. Z., et al., “Toward an Expanded Vision of Clinical Ethics Education: From the Individual to the Institution,” Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 1, no. 3 (1991): 225-45. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10114319/

1990: Publication of Daniel Callahan’s What Kind of Life? The Limits of Moral Progress

Callahan critiques society’s technological imperative in medicine of the maintenance of health and the extension of life at all costs with insufficient attention to the telos of human life and health: the kind of life we should live. He asks the ancient question again: What in the modern medical technological age constitutes the good life?

D. Callahan,What Kind of Life? The Limits of Moral Progress(New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990).

1995: The SUPPORT Trial on End-of-Life Care & Dying Well in the Hospital: The Lessons of SUPPORT

A two-year prospective observational study (phase I) with 4301 patients followed by a two-year controlled clinical trial (phase II) with 4804 patients and their physicians randomized to the intervention group or control group in five teaching hospitals in the United States that showed substantial shortcomings in care for seriously ill hospitalized adults (phase I) and failure of intervention to improve care or patient outcomes (phase II). This was followed by a foundational document on end-of-life care practices, 12 commenters discuss the implications of the SUPPORT study.

The SUPPORT Principal Investigators. “A Controlled Trial to Improve Care for Seriously Ill Hospitalized Patients. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments (SUPPORT),” Journal of the American Medical Association. 274, no. 20 (1995): 1591-98.

E. H. Moskowitz and J. Lindemann, “Dying Well in the Hospital: The Lessons of SUPPORT,”special report, Hastings Center Report25, no. 6 (1995): S2-S36.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7474243/

2014: Publication of Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End

Atul Gawande writes in this book about the struggle in the medical establishment to forthrightly face the inevitability of death and how to reform practice to improve the experiences of patients as they approach the end of their life.

A. Gawande, Being Mortal: Medicine and What Matters in the End. (New York: Metropolitan Book, Henry Holt and Company, 2014). http://atulgawande.com/book/being-mortal/

2016: Medicare Reimbursement for Conversations about End-of-Life Care

Medicare begins to reimburse physicians for conversations about preferences for end-of-life care. Long an issue of bipartisan agreement, the idea of reimbursing for discussions about end-of-life preferences had become a political lightening rod and was removed from the 2010 Affordable Care Act after it was mischaracterized as a “death panel” during the presidential election campaign and subsequent debates over the Act.

https://khn.org/news/doctors-ponder-delicate-talks-as-medicare-pays-for-end-of-life-counsel/