Ethics and Brain Injury

Selected resources from The Hastings Center.

Bioethics Briefings:

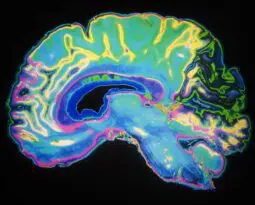

Brain Injury: Neuroscience and Neuroethics

Not long ago, patients with severe brain injury and no apparent consciousness were presumed to be in a permanent vegetative state, without hope of recovery. New evidence shows that some of these patients are actually in the minimally conscious state, meaning they can comprehend speech and sometimes recover, even after a decade. Distinguishing the vegetative state from the minimally conscious state requires careful clinical evaluation. Read our briefing to consider: What are the ethical implications of differences between brain states?

From Hastings Bioethics Forum:

- Individuals Declared Brain-Dead Remain Biologically AliveA remarkable experiment raises anew questions about whether brain-death is really death.

- Revising the Uniform Determination of Death Act: Response to Miller and Nair-CollinsTo address recent lawsuits that question whether the persistent of hormonal functions is consistent with death by neurologic criteria (such as the case of Jahi McMath), we proposed specific mention in a UDDA that loss of hormonal functions is not required for declaration of death by neurologic criteria.

- Lincoln’s Promise: Congress, Veterans, and Traumatic Brain InjuryPerhaps we were naïve. Our plan was relatively simple: we would chart the legislative evolution of programs for veterans with traumatic brain injuries (TBI) to identify…

- Bioethics and the Dogma of “Brain Death”Two cases involving “brain death” have received considerable public attention, including commentary by several well-known bioethicists. In commenting on these cases the bioethicists have stated, in…

- An ICU Nurse Discusses Brain DeathBrain death is an immensely challenging concept to grasp, even for health care providers. The patients look like any other patient in the intensive care unit;…

- “End of Life,” Value Judgments, and Ending LivesIt may be more than just discrimination at work. As is to be expected, once people start reflecting on an essay as important and provocative as…

- Disability DiscriminationA powerful essay in the July-August Hastings Center Report describes a chilling encounter between a physician and a seriously ill disabled patient. The author, William J. Peace, who…

- New Hope for Detecting Consciousness in Vegetative Patients: Ethical ImplicationsPatients diagnosed as being in a persistent vegetative state have figured prominently in the law and medical ethics relating to end-of-life decisions since the case of…

- “M,” Polly, and the Right to DieAnother landmark right-to-die case hit the U.K. headlines last week. A High Court judge ruled, in W v M & Ors [2011] EWHC 2443 (Fam), that…

From Hastings Center Report:

Locked In

First published: 20 December 2022

Abstract

Tiffany was seventeen when injury to her brain stem put her in the intensive care unit on life-sustaining treatment and in a permanently locked-in state—fully conscious but able to control no bodily movements other than her eye movements. As a clinical ethicist at the hospital, I was consulted by her neurologist, who had established a blink-once-for-yes, twice-for-no system of communication so that Tiffany could respond to questions. Her mother wanted Tiffany to continue receiving treatment that could prolong her life for years, potentially decades. In a meeting with the neurologist and family, I felt like suggesting what nobody seemed willing to suggest: that we should ask Tiffany what she wants.

When No One Notices: Disorders of Consciousness and the Chronic Vegetative State

First published: 20 August 2019

Abstract

On January 5, 2019, the Associated Press reported that a woman thought to have been in the vegetative state for over a decade gave birth at a Hacienda HealthCare facility. Until she delivered, the staff at the Phoenix center had not noticed that their patient was pregnant. The patient was also misdiagnosed.

Misdiagnosis of patients with disorders of consciousness in institutional settings is more the norm than the exception. Misdiagnosis is also connected to a broad and extremely significant change in the understanding of the vegetative state—a change that the field of bioethics has not yet fully taken into account. In September 2018, the American Academy of Neurology, the American College of Rehabilitation Medicine, and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research issued a comprehensive evidence-based review on disorders of consciousness and an associated practice guideline on the care of these patients. These landmark publications update the 1994 Multi-Society Task Force Report on the Vegetative State, which subcategorized the persistent vegetative state as either persistent (once the vegetative state lasted one month) or permanent (once the vegetative state lasted three months after anoxic injury or twelve months after traumatic injury). Noting that 20 percent of patients thought to be permanently unconscious might regain some level of consciousness, the new guideline has eliminated the permanent vegetative state as a diagnostic category, replacing it with the chronic vegetative state.

The Relational Potential Standard: Rethinking the Ethical Justification for Life-Sustaining Treatment for Children with Profound Cognitive Disabilities

First published: 03 July 2019

Abstract

In this era of rapidly advancing biomedical technologies, it is not unusual for parents of children with profound cognitive disabilities to ask clinicians to provide invasive life-sustaining treatments. Parental requests for such interventions pose a moral dilemma to the treating medical team, as there may be a discrepancy between the team’s perception of the child’s best interest and the apparent rationale underlying a parent’s request. This gap highlights the limitation of the best interest standard in cases where, due to a neurodevelopmental disorder or brain injury, the child’s capabilities are severely limited and their interests may be difficult to discern. The harm principle is also inadequate for decision-making in response to these parental requests. To address these limitations, and inspired in part by John Arras’s work on the relational potential standard, we propose an integration of care ethics within pediatric decision-making using a new version of this standard. The potential for children to be in caring and loving relationships with their parents, what we will call “relational potential,” may provide an ethical justification for clinicians to support parental requests for life-sustaining treatments.

DCDD Donors Are Not Dead

First published: 25 December 2018

Abstract

According to international scientific medical consensus, death is a biological, unidirectional, ontological state of an organism, the event that separates the process of dying from the process of disintegration. Death is not merely a social contrivance or a normative concept; it is a scientific reality. Using this paradigm, the international consensus is that, regardless of context, death is operationally defined as “the permanent loss of the capacity for consciousness and all brainstem function. This may result from permanent cessation of circulation or catastrophic brain injury. In the context of death determination, ‘permanent’ refers to loss of function that cannot resume spontaneously and will not be restored through intervention.” The word “permanent” replaces “irreversible” (used in the United States’ 1980 Uniform Declaration of Death Act) in this new definition, arguably invented to allow donation after circulatory determination of death (DCDD) while still complying with the dead donor rule. I will show that this invention fails, for at least four reasons.

Brain Death and the Law: Hard Cases and Legal Challenges

First published: 25 December 2018

Abstract

The determination of death by neurological criteria—“brain death”—has long been legally established as death in all U.S. jurisdictions. Moreover, the consequences of determining brain death have been clear. Except for organ donation and in a few rare and narrow cases, clinicians withdraw physiological support shortly after determining brain death. Until recently, there has been almost zero action in U.S. legislatures, courts, or agencies either to eliminate or to change the legal status of brain death. Despite ongoing academic debates, the law concerning brain death has remained stable for decades. However, since the Jahi McMath case in 2013, this legal certainty has been increasingly challenged. Over the past five years, more families have been emboldened to translate their concerns into legal claims challenging traditional brain death rules. While novel, these claims are not frivolous. Therefore, it is important to understand them so that we can address them most effectively.

Lessons from the Case of Jahi McMath

First published: 25 December 2018

Abstract

Jahi McMath’s case has raised challenging uncertainties about one of the most profound existential questions that we can ask: how do we know whether someone is alive or dead? The case is striking in at least two ways. First, how can it be that a person diagnosed as dead by qualified physicians continued to live, at least in a biological sense, more than four years after a death certificate was issued? Second, the diagnosis of brain death has been considered irreversible; in fact, there has never been a case of a person correctly diagnosed as brain-dead who improved to the point that the person no longer fulfilled the diagnostic criteria. If the neurologist Alan Shewmon is correct that, prior to her cardiac arrest in June 2018, McMath no longer met the criteria for brain death and was actually in a minimally conscious state, this case could have momentous implications for how we think about this diagnosis going forward. In this essay, I will offer a hypothesis that could, perhaps, explain both these aspects of the case. The hypothesis is based on differences in how we distinguish between biological and legal categories. The law tends to prefer to draw bright-line distinctions between categories, whereas biological categories tend to fall along a spectrum, without sharp distinctions.

The Case of Jahi McMath: A Neurologist’s View

First published: 25 December 2018

Abstract

From the start, I followed the case of Jahi McMath with great interest. In December 2013, she clearly fulfilled the diagnostic criteria for brain death. As a neurologist with a special interest in chronic brain death, I was not surprised that, after she was flown to New Jersey, where she became statutorily resurrected and was treated as a comatose patient, Jahi’s condition quickly improved. In 2014, her family reported that she sometimes responded to simple motor commands. I shared the general skepticism regarding these reports, assuming that the family was in denial and was misinterpreting spinal myoclonus (a rapid, involuntary twitch generated by the spinal cord) as volitional. The family had noticed that when Jahi’s heart rate was above eighty beats per minute, she was more likely to respond, as though the heart rate reflected some sort of inner level of arousal. So they began to make video recordings. I have been privileged to be entrusted with copies of these recordings, forty-eight of which proved suitable for assessing alleged responsiveness. All have been certified by a forensic video expert as unaltered. The first thing that struck me was that the great majority of the alleged responses were not spinal myoclonus. In fact, they did not resemble any type of spontaneous, involuntary movement described in patients paralyzed from high spinal cord lesions.

Revisiting Death: Implicit Bias and the Case of Jahi McMath

First published: 25 December 2018

Abstract

For nearly five years, bioethicists and neurologists debated whether Jahi McMath, an African American teenager, was alive or dead. While Jahi’s condition provides a compelling study for analyzing brain death, circumscribing her life status to a question of brain death fails to acknowledge and respond to a chronic, if uncomfortable, bioethics problem in American health care—namely, racial bias and unequal treatment, both real and perceived. Bioethicists should examine the underlying, arguably broader social implications of what Jahi’s medical treatment and experience represented. On any given day, disparities in the quality of health care and health outcomes for people of color in comparison to whites are evidenced in American hospitals and clinics. These disparities are not entirely explained by differences in patient education, insurance status, employment, income, expressed preference for treatments, and severity of disease. Instead, research indicates that, even for African Americans able to gain access to health care services and navigate institutional nuances, disparities persist across a broad range of services, including diagnostic screening and general medical care, mental health diagnosis and treatment, pain management, HIV-related care, and treatments for cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and kidney disease.

Empty Spaces

First published: 20 September 2017

Abstract

“I’m Jewish, you know, and my mother said, ‘Always trust the rabbis.’” I never heard Mr. Weisman’s refrain from his own lips. I never heard him say any words all. By the time I met him he was in a vegetative state, a man on the precipice of invisibility—white hair, thin pale limbs, melting into sheets of the same color. When I think about Mr. Weisman, I see empty spaces—the absence of his voice, the too-large bed for his shrinking frame, the always-empty chair by his bedside, and most of all, the myriad gaps in his life story. He was what in hospitals is often called a “patient alone”: someone who lacks decisional capacity and has no surrogate to make medical decisions for him. Mr. Weisman’s aloneness prompted his primary team to consult our bioethics service in order to formulate goals of care for him, including the possibility of hospice care.

The Afterlife of Terri Schiavo

First published: July 2005

Abstract

Shortly after Terri Schiavo’s autopsy was released, Not Dead Yet, a disability advocacy group, issued a press release asserting that the autopsy results “leave the central issues in her life and death unanswered.” Not Dead Yet contested the view that the autopsy bolstered the diagnosis of a persistent vegetative state. It supported its contention by calling attention to comments by Stephen J. Nelson, the neuropathologist who examined Schiavo’s brain during the autopsy.

Nelson rightly noted that “The persistent vegetative state, and minimally conscious state, are clinical diagnoses, not pathologic ones,” and that “Neuropathologic examination alone of the decedent’s brain—or any brain, for that matter—cannot prove or disprove a diagnosis of persistent vegetative state or minimally conscious state.”

What We talk about When We Talk about Ethics

First published: 09 January 2014

Abstract

I was recently invited to talk about ethics with the staff of a level-three neonatal intensive care unit. They presented a case featuring a full-term baby born by emergency caesarean-section after a cord prolapse that caused prolonged anoxia. Her initial pH was 6.7. She was intubated and resuscitated in the delivery room. Her Apgar score remained at 1 for ten minutes. Further evaluation over the next two days revealed severe brain damage. Her prognosis was dismal.

The doctors recommended a do-not-resuscitate order. The parents agreed. The doctors suggested a gastrostomy tube. The parents disagreed. Instead, they requested that fluid and nutrition be discontinued. The emotions in the room, as we started to discuss the case, were strong and discordant. Eventually, the conversation wound down. They turned, expectantly, to the visiting bioethicist.

Rethinking Disorders of Consciousness: New Research and Its Implications

First published: March 2005

Abstract

Over the past several years, deciding whether to withdraw life-sustaining therapy from patients who have sustained severe brain injuries has become much more difficult. The problem is not the religious fundamentalism that infused the debate over the care of Terri Schiavo, the Florida woman in a permanent vegetative state whose case has drawn national attention. Rather, the difficulty stems from emerging knowledge about the diagnosis and physiology of brain injury and recovery. The advent of more sophisticated neuroimaging techniques like MRI and PET scans, in tandem with electrophysiologic and observational studies of brain-injured patients, have led to an effort to differentiate disorders of consciousness more precisely. The crude categories that have informed clinical practice for a quarter century are becoming obsolete.

Erring on the Side of Theresa Schiavo: Reflections of the Special Guardian ad Litem

First published: May 2005

Abstract

Four commentators discuss what made it so difficult, why it was more complex than most realized, and what we should do differently.

The Schiavo Case: A Medical Perspective

First published: May 2005

Abstract

The shocking, clamoring, and very public intrusion into the life and death of Terri Schiavo underscored the damage done over recent decades to the personal nature of medical care and to the privacy many desire for such personal matters. But medical care is personal, and in more than one sense. It is personal because it involves the care of persons by persons. It is personal because it rests on a relationship between the caregivers and the patient or the patient’s surrogates. Most of all, it is personal because sickness, whatever other professional or community ramifications it may have, is something that happens to a person. Except in trivial illness, almost nothing of persons is untouched, including their past and future, everyday life, spirituality, knowledge—everything. Especially deeply touched, however, are the sick person’s relationships. Sickness highlights the intricacies and complexities of families and relationships and how these change as we grow up, marry, acquire new responsibilities, and so forth, all of which is determined in part by our culture and society. The intervention of the law into Schiavo’s care is a reflection of the complications that relationships may present when personal troubles arise.

Schiavo’s Legacy: The Need for an Objective Standard

First published: May 2005

Abstract

Like many who teach and write about bioethics, I was startled by the intense national interest in the case of Terri Schiavo. Her medical situation closely resembled that of Karen Ann Quinlan, Nancy Cruzan, and other patients, and for people familiar with end-of-life topics, the issues seemed settled. There were established rules and principles to guide the case toward a resolution. But perhaps the public response was not so surprising. Over the past three decades, clinicians and legal authorities have constructed a basic approach to treatment decisions for incapacitated patients, but as the passions this latest case unleashed suggest, this approach is both unfinished and vulnerable to challenge. Schiavo exposed weaknesses and gaps that demand our attention.

Recovery from Persistent Vegetative State?: The Case of Carrie Coons

First published: July 1989

Abstract

How reliable is a diagnosis of irreversible unconsciousness? In a unique case in New York, a state Supreme Court judge vacated an order allowing removal of life-sustaining treatment after Carrie Coons showed signs of recovery from a diagnosed vegetative state.

From Hastings Center Bioethics Timeline:

1968: Definition of Death

An ad hoc committee at Harvard Medical School reexamined the definition of brain death and defined irreversible coma, or brain death. These definitions and guidelines would facilitate retrieval of organs for transplantation.

“A Definition of Irreversible Coma: Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death,” Journal of the American Medical Association 205 no. 6 (1968): 337-40.

1975: Karen Quinlan

On April 15, 1975, at the age of 21, Karen Quinlan became unconsciousness after consuming alcohol and Valium at a party. She lapsed into a coma followed by a persistent vegetative state. Her parents asked that she be removed from her ventilator, which they believed constituted extraordinary means of prolonging her life. They filed suit in NJ Superior Court on September 12, 1975. See 1976 entry for In Re Quinlan decision.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2495105/

1976: In Re Quinlan

The New Jersey Supreme Court decided that Joseph Quinlan, father of comatose ventilator dependent patient, Karen Ann Quinlan, may assert her right to privacy and that, pending review by a hospital ethics committee (HEC), that right is broad enough to encompass discontinuation of Karen Ann Quinlan’s ventilator support. The decision confirmed patients and surrogates legal right to refuse life sustaining medical interventions. It also publicized the concept of hospital ethics committees and catalyzed a national discussion of end-of-life issues, couched in terms of refusing “extraordinary,” or “heroic,” treatment.

In Re Quinlan, 70 N.J. 10; 355 A.2d 647 (1976)

https://law.jrank.org/pages/9617/Quinlan-in-Re.html

1990: Cruzan, U.S. Supreme Court

In 1983, Nancy Beth Cruzan required cardiopulmonary resuscitation after an automobile accident. She never regained consciousness. While she was weaned off a ventilator, her parents asked to have her feeding tube withdrawn. The hospital refused the request based on Missouri’s requirement for clear and convincing evidence of a patient’s wishes before withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration. After Missouri prevailed in the state Supreme Court, the Cruzan’s appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, which holds that the Constitution’s 14th Amendment due process liberty interest supports an individual’s right to refuse life sustaining medical treatment, including artificial nutrition and hydration; the court finds that Missouri may require the clear and convincing evidentiary standard of the patient’s wishes; evidence of her wishes is subsequently uncovered and Nancy Cruzan is allowed to die. The Cruzan case, the first U.S. Supreme Court decision on ethical issues at end of life, established a federal 14th Amendment due process liberty interest to be free of unwanted medical treatment, to which all federal and state courts must adhere.

Cruzan by Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Dept. of Health, 497 U.S. 261, 110 S.CT. 2841, 111 L.ED.2D 224 (1990)

https://www.oyez.org/cases/1989/88-1503

1993: Airedale NHS Trust vs Tony Bland, House of Lords, United Kingdom

The U.K. House of Lords authorized the removal of the feeding tube from Anthony (Tony) Bland, who had been in a persistent vegetative state since being crushed by a crowd during a football match in Hillsborough in 1989. Parents and physicians agreed to terminate life-prolonging medical treatment in the form of artificial nutrition and hydration. The hospital successfully applied for a court order allowing the withdrawal of artificial nutrition and hydration. This was the first English patient to be allowed by the court to die by this means.

Airedale NHS Trust vs Tony Bland (1993) 1 All ER 821 HL. https://www.globalhealthrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/HL-1993-Airedale-NHS-Trust-v.-Bland.pdf

2005: The Death of Terri Schiavo

Terri Schiavo had a cardiac arrest at age 26 and developed anoxic brain damage that resulted in a persistent vegetative state, requiring prolonged artificial life support, including a feeding tube. Her husband sought to remove the feeding tube because he felt that she would not have wanted prolonged artificial life support without the prospect of recovery. Terri’s parents disputed these assertions and challenged the diagnosis and their son-in-law’s decision-making authority as her guardian. The legal and political arguments pertaining to this case ultimately led President George W. Bush to sign legislation to move the case to the federal courts. Appeals to the federal court system upheld the decision to remove the feeding tube. This occurred and led to her death.

Bush v. Schiavo, 885 So. 2d 321, 336-37 (Fla. 2004)

An Act for the Relief of the Parents of Theresa Marie Schiavo, Pub. L. No. 109-3, 119 Stat. 15 (2005).

Schiavo ex rel. Schindler v. Schiavo, 358 F. Supp. 2d 1161, 1167 (M.D. Fla. 2005).

https://time.com/3763521/terri-schiavo-right-to-die-brittany-maynard/

2013: Controversy over Maintaining Ventilation after Declaration of Brain Death

Jahi McMath is declared brain-dead in California and her family wishes to maintain her body on mechanical ventilation.

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/04/us/a-brain-is-dead-a-heart-beats-on.html

McMath v. State of California U.S. N.D. Calif. No. 3:15-cv-06042; (Dismissal) U.S. N.D. Calif. No. 4:15-cv-06042-HSG