Hastings Center News

Call to Revisit a “Line in the Sand” Limiting Human Embryo Research

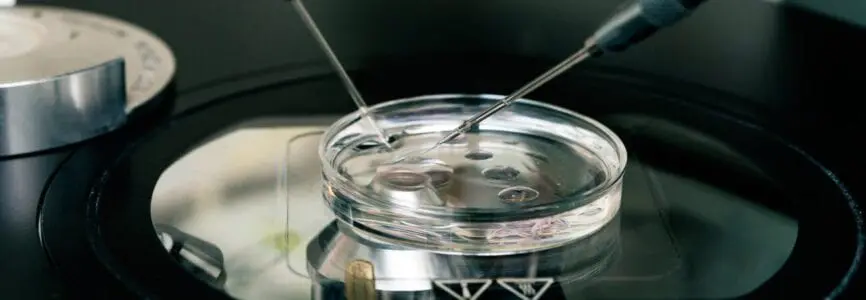

Josephine Johnston, director of research and a research scholar at The Hastings Center, has joined two co-authors in proposing a reexamination of an internationally recognized rule limiting in vitro research on human embryos to 14 days post-fertilization. Writing in the journal Nature, they respond to technological advances that have nearly doubled the length of time that embryos can be sustained in vitro, from about seven days until 12 to 13 days.

These advances “put human developmental biology on a collision course with the ‘14-day rule’ – a legal and regulatory line in the sand that has for decades limited in vitro human-embryo research to the period before the ‘primitive streak’ appears,” they write. The formation of the primitive streak is biologically significant because before this point, embryos can split in two or fuse together.

The authors note that while some people believe the primitive streak is also a morally significant moment in embryo development, the public’s views differ widely on the stage at which embryos and fetuses attain sufficient moral status that research should be prohibited. Their analysis of policy development in this area shows that the 14-day rule “was never intended to be a bright line denoting the onset of moral status in human embryos.” Rather, its chief goals were to carve out a space for embryo research to go forward while also accommodating many of these diverse moral views.

They write that, thus far, the rule has produced great benefit by identifying a time period within which research could take place. “The alternatives at each extreme — banning embryo research altogether or imposing no restrictions on embryo use — would not have made for good public policy in a pluralistic society,” write Johnston; Insoo Hyun, a bioethicist at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine; and Amy Wilkerson, a research administrator at The Rockefeller University. But now that research is butting up against that rule, it makes sense to revisit its rationale and purpose.

Johnston says that a reexamination of the rule need not lead to overturning it. “The 14-day rule was first developed more than 35 years ago, when both the science and the public discussion of embryo research were in different places than they are today. The passage of time alone suggests that a reexamination would be prudent,” she says. “We should ask what the rule means for science and policy today, and consider whether it still fulfills its dual purpose of delineating a space for valuable scientific research while respecting the deeply held views of a diverse society. We believe it is important to openly consider both the scientific merits of research beyond 14 days and the ethical concerns that such research would raise.”