The Ethical Implications of Social and Behavioral Genomics

Research on how genomic differences are associated with differences in a wide variety of human social and behavioral characteristics, or phenotypes, including anxiety, subjective well-being, and educational attainment, is increasing. And there is ongoing concern about its misinterpretation and misuse.

A consensus report, Wrestling with Social and Behavioral Genomics: Risks, Potential Benefits, and Ethical Responsibility, provides direction for research and communications in this area of study with both significant social risks and potential benefits. It is accompanied by an article, Wrestling with Public Input on an Ethical Analysis of Scientific Research that describes a fledgling effort to integrate community perspectives on the ethics of this research. These were published in a Hastings Center special report, The Ethical Implications of Social and Behavioral Genomics, in April 2023. Co-editors are Erik Parens and Michelle N. Meyer.

Key questions of the consensus report

What are the risks and what are the potential benefits of social and behavioral genomics (SBG) research? What is justifiable and unjustifiable social and behavioral genomics research? What can genetics tell us about social outcomes as complex as, for example, educational attainment, and what should we do with that information?

Major points about which the authors of the report agree

- Risks of SBG research include: Stigmatization, discrimination, misconstruing race and ethnicity as biological concepts, inappropriate applications of SBG research, genetic fatalism (nothing I can do about how I was born), genetic distractionism (focus on genetics rather than effective environmental interventions).

- Potential benefits of SBG research include: Better understanding of environmental causes and limits of genomic influence, advancing health research, improving trials using polygenic indexes, and, through these, indirectly improving policies.

- Downstream uses of social and behavioral polygenic indexes (PGIs): It will rarely be straightforward to translate SBG research and the PGIs they produce into scientifically and ethically acceptable practices or policies (e.g., in education, employment, or medicine), and SBG research should generally not be used to deny people opportunities or benefits.

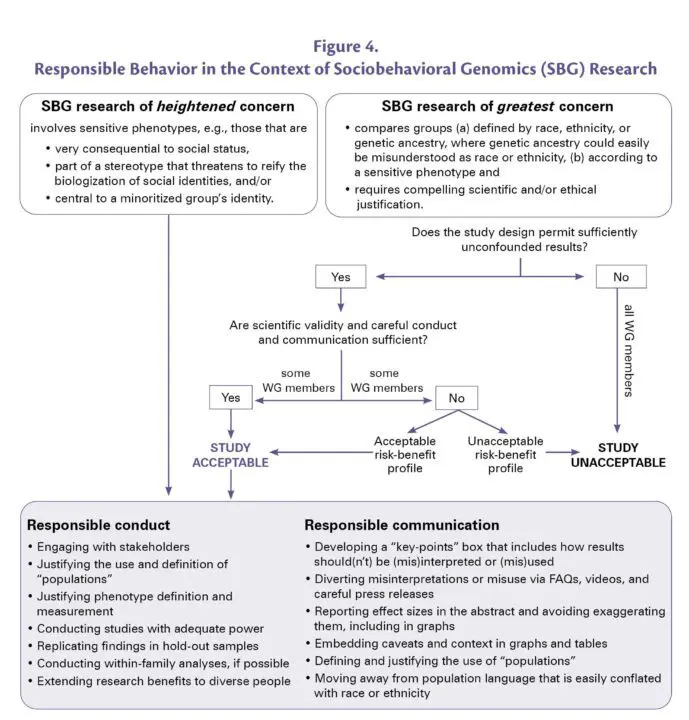

- SBG research of heightened concern: Genomic research that compares individuals within a group according to a sensitive social or behavioral phenotype requires special attention to responsible conduct and communication.

- SBG of greatest concern: SBG research on sensitive phenotypes that seeks to compare groups defined by race, ethnicity, or genetic ancestry, where genetic ancestry could easily be misunderstood as race or ethnicity, should not be conducted, funded, or published without a compelling justification. This justification requires, at minimum, a convincing argument that the study’s design could yield scientifically valid results.

Areas where authors of the report disagree

- How likely science is to uncover causal mechanisms underpinning associations between genetic variants and social or behavioral phenotypes

- How useful or otherwise valuable prediction is, scientifically or practically, in the absence of understanding causal mechanisms

- Whether any downstream use of social and behavioral polygenic indexes (PGIs) (e.g., in education, employment, or reproductive or clinical medicine), would ever be ethically justified

- How likely it is that, in the future, SBG research that attempts to compare different racial, ethnic, or genetic ancestral groups will be scientifically valid

- Whether, to be ethically justified, scientifically valid SBG research of greatest concern must have a socially favorable risk-benefit profile.

Figure 4 from: Michelle N. Meyer, Paul S. Appelbaum, Daniel J. Benjamin, Shawneequa L. Callier, Nathaniel Comfort, Dalton Conley, Jeremy Freese, Nanibaa’ A. Garrison, Evelynn M. Hammonds, K. Paige Harden, Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, Alicia R. Martin, Daphne Oluwaseun Martschenko, Benjamin M. Neale, Rohan H. C. Palmer, James Tabery, Eric Turkheimer, Patrick Turley, and Erik Parens, “Wrestling with Social and Behavioral Genomics: Risks, Potential Benefits, and Ethical Responsibility,” in The Ethical Implications of Social and Behavioral Genomics, ed. Erik Parens and Michelle N. Meyer, special report, Hastings Center Report 53, no. 2 (2023): S2-S49. DOI 10.1002/hast.1477

Wrestling with Public Input on an Ethical Analysis of Scientific Research

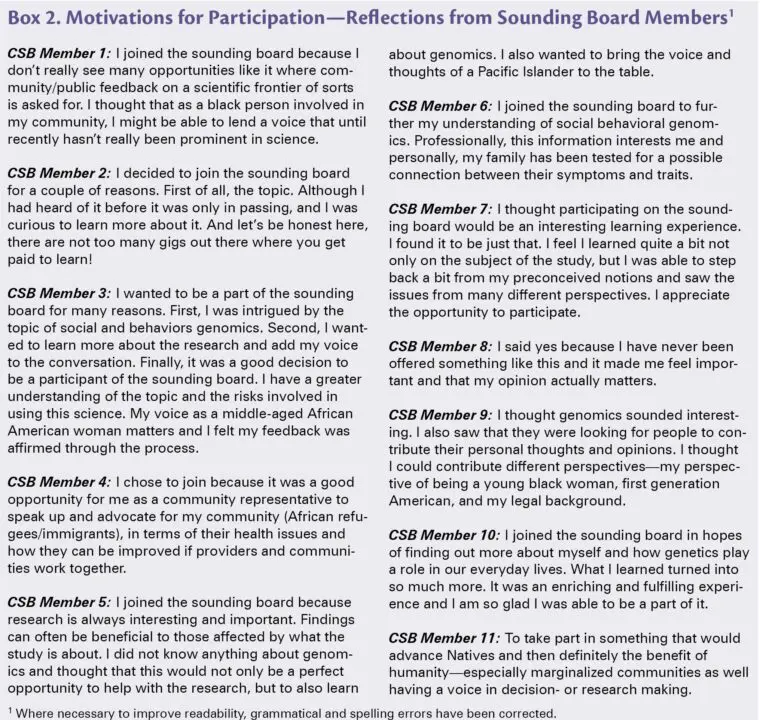

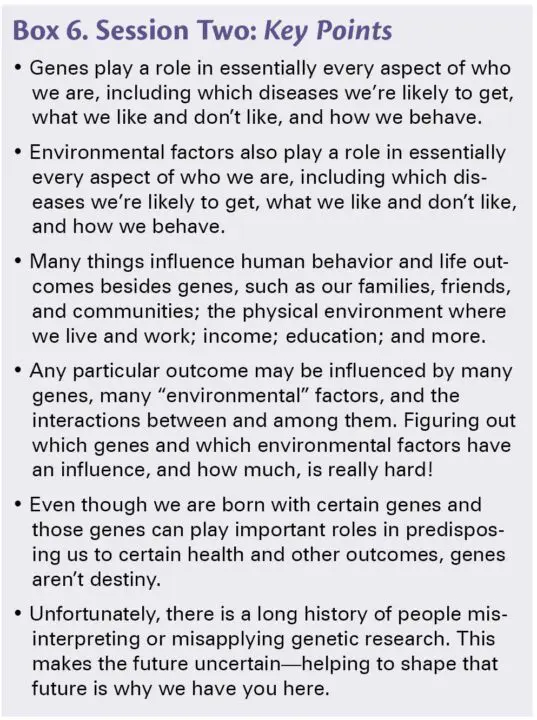

It is increasingly well accepted that engaging members of the public in empirical research is critical to ensuring that research addresses the needs, and is consistent with the values, of the people it is meant to serve. This article describes a fledgling effort to integrate community perspectives into Wrestling with Social and Behavioral Genomics, a normative ethics research project. If ever there was an area of normative scholarship that warranted input from members of the public, it would seem to be scholarship concerning the ethics of social and behavioral genomics (SBG) research. After all, it is often members of the public—in particular, those with relatively less income or education, those with disabilities, sexual and gender minorities, racialized-minoritized communities, and those who have been impacted by the criminal justice system—who have experienced harms in the wake of scientific interest in genetic differences and human behavior. Box 2 below describes the community sounding board members’ reasons for participating in this research. Box 6 tells community sounding board members what SBG researchers study and how.

From: Daphne Oluwaseun Martschenko, Shawneequa Callier, Nanibaa’ A. Garrison, Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, Patrick Turley, Michelle N. Meyer, and Erik Parens, “Wrestling with Public Input on an Ethical Analysis of Scientific Research,” in The Ethical Implications of Social and Behavioral Genomics, ed. Erik Parens and Michelle N. Meyer, special report, Hastings Center Report 53, no. 2 (2023): S50-S65. DOI: 10.1002/hast.1478

Basic terms for Social and Behavioral Genomics

| Phenotype: an individual’s observable or measurable traits, such as lifetime risk of Type 2 diabetes, height, personality, or educational attainment. A person’s phenotype is determined by both their genomic makeup (genotype) and environmental factors. |

| Social and Behavioral Genomics (SBG) research: studies that incorporate information on genomic differences among people to investigate how behavioral and social phenotypes are influenced by genes, environments, and their interplay. Such phenotypes span a wide range, including substance use, subjective well-being, risk-taking, empathy, income, and educational attainment. |

| Polygenic Indexes (PGIs) or Polygenic Risk Scores or Polygenic Scores: a new tool that sums up the tiny weights, identified by a GWAS, of each genetic variant’s association with a medical, anthropometric, behavioral, or social phenotype and predicts a person’s odds of having that phenotype. Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWASs): research that involves scanning the genomes of many people to find genetic variants associated with particular medical, anthropometric, behavioral, or social phenotypes. |

The consensus report recommends clear communications about social and behavioral genomics research, including the use of FAQs.

See past issues of the related Braingenethics (2014-2020) (2021-23) newsletter from the collaboration with Columbia University Medical Center/CEER. See also event videos from the Center for ELSI Research on Psychiatric, Neurologic & Behavioral Genetics.