Bioethics Forum Essay

More and “Better” Babies: The Dark Side of the Pronatalist Movement

There is growing concern that falling fertility rates will lead to economic and demographic catastrophe. The social and political movement known as pronatalism looks to combat depopulation by encouraging people to have as many children as possible. But not just any kind of children.

While pronatalists advocate for progressive social policies that may incentivize childbearing, like free childcare, high profile figures in tech, like Coinbase co-founder Brian Armstrong, OpenAI co-founder Sam Altman, and entrepreneur-turned-government advisor Elon Musk, are seeking to optimize for the “best” babies possible. They are turning to novel assisted reproductive genetic technologies to do so, including polygenic embryo selection. Also known as preimplantation genetic testing for polygenic disorders (or PGT-P), the technology provides prospective parents with information on genetic risk for complex (multi-gene) traits. Companies offer genetic testing for traits ranging from health conditions like heart disease to, more controversially, behavioral traits like intelligence. The service, despite having limited accuracy, is backed by millions of dollars invested by pronatalist “tech optimists” like Altman, Armstrong, PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel, and Etherium’s Vitalik Buterin.

The technologies that are being financed and used by tech-elite pronatalists are new. The push to have as many babies as possible and the best babies possible is not new. The agenda of these techno-optimist pronatalists bears a striking resemblance to America’s 20th century eugenics movement and the Better Babies contests that were a part of it.

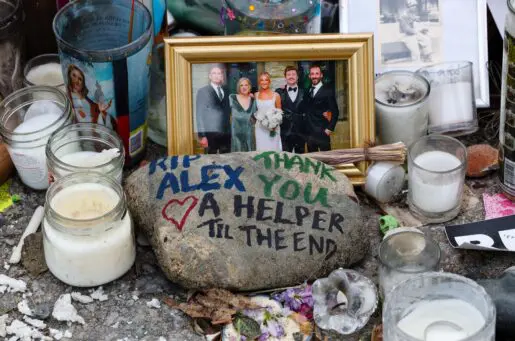

Throughout the early 20th century, state fairs displayed the best America had to offer: mammoth-sized produce, prize-winning livestock, and competitions between children ages 6 months to 4 years. Babies and children were measured, weighed, and subjected to a battery of cognitive tests by a team of doctors, nurses and psychologists who served as judges for Better Babies contests. Winners often had a perfect score. Their height, weight, body proportions, and overall physical appearance were deemed just right. They’d aced their mental and developmental tests.

The intentions behind Better Baby contests were not initially sinister. The first Better Baby contest was held at the Louisiana State Fair in 1908– the brainchild of the former schoolteacher Mary DeGarmo. DeGarmo was alarmed by the country’s high infant mortality rate. She hoped that the contests, and the cash prizes that came with winning, would encourage parents to take better care of their children. With the help of medical doctor Jacob Bodenheimer, she developed a set of criteria for judging which babies were “scientifically better”–setting an idealized standard.

But the contests were restricted to white children and soon became a way for the American eugenics movement to advance a racial purity campaign. The parents of Better Baby contest winners were encouraged to have more children–an example of “positive eugenics”: a set of policies intended to improve the genetic stock of humanity by increasing reproduction among its most eminent members. A 1939 editorial in the high-profile science journal Nature explained:

“We need not wait for full knowledge of the human genetic constitution, to construct human beings as an engineer constructs a bridge. . . .The need is urgent for a simple national eugenic policy which will induce the better endowed to have larger families, and history will not spare us if we do not set to work at once to carry it out.”

Better Baby contests fizzled away and the eugenics movement lost favor in the aftermath of World War II. Pronatalist sentiment, however, never died.

Today, pronatalism is firmly coupled with “free market eugenics,” meaning it operates through consumer demand rather than state coercion. A small but powerful group of tech elites are emerging as its leaders.

“Population collapse is coming,” warned Elon Musk in a post on X. The tech entrepreneur is the father of at least 14 children. Pronatalists appear to have the support of the Trump administration. Simone Collins, a former venture capitalist who founded Pronatalist.org with her husband Malcom Collins, is the author of a recent Trump executive order calling for “motherhood medals” for women who’ve had more than six children. The couple have four with a fifth on the way. Like Altman, Armstrong, and Musk, the Collinses have used PGT-P.

In the Collinses view, PGT-P gives their future offspring the “best possible roll of the dice.” PGT-P companies agree with them. Company marketing calls on consumers to “have healthy babies” and “mitigate more risks.” “These babies have great genes,” claims a current advertisement from Nucleus Genomics. “Have your best baby,” reads another. Slogans like these are markedly similar to a 1913 Woman’s Home Companion magazine advertisement for Better Baby contests: “healthy babies, standardized babies, and always, year after year, Better Babies.”

Pronatalists like the Collinses argue that impending demographic collapse “disproportionately affects society’s most vulnerable members.” They seem to see themselves as belonging to that vulnerable group. Like 20th century eugenics movement leaders, the Collinses are concerned about the dilution of America’s genetic stock: “These people – the dumb ones – are going to be more and more of the general population as time goes on,” Malcom lamented in one of his podcast episodes, “and so they will be electing and building bureaucracies that make it harder and harder for the geniuses to do their jobs.” He’s concerned that fertility rates in “low-productivity groups” are higher than those “high productivity groups” when the reverse ought to be true; he believes that people like him are the ones who ought to be having more children.

In the long run, ideals and intentions may count more than the efficacy of the technology itself. Outwardly, the pronatalist movement claims that it wants to help create a world where people have as many children as possible; some of its wealthiest members also say that they make financial investments in technologies like PGT-P because they want to help parents and prevent disease. Beneath the surface, however, a darker story emerges. Just as the 20th century eugenics movement leveraged Better Baby contests to reward and encourage those they thought possessed the “best genes” to reproduce, baby-making using reproductive technologies appears to be reserved for those who are thought to be genetically superior to everyone else. The tech elite leaders of today’s pronatalist movement are leveraging prohibitively expensive reproductive technologies like PGT-P to encourage a select group to have the most and the “best” children possible.

Daphne O. Martschenko, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Stanford Center for Biomedical Ethics. She is co-author of the book What We Inherit, which unpacks contentious social, ethical, and policy issues related to the DNA revolution, and is working on her second book, TechnoBaby: The Troubling Race to Make and Raise ‘Better’ Babies. She is also a co-creator of Genomic Findings on Human Behavior and Social Outcomes: FAQs. Bluesky: @daphmarts.bsky.social

Julia E. H. Brown, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of California, San Francisco, and incoming senior research fellow at the Reproduction in Society Group at the Monash Bioethics Center at Monash University in Australia. Her forthcoming podcast, In Utero, will discuss lived experiences of and interdisciplinary perspectives on emerging prenatal technologies. Bluesky: @juliaehbrown.bsky.social

What do PGT-P proponents who align on the political right propose to do with the less than “best” embryos? Destruction is not consistent with the assertion that life begins at conception.