Bioethics Forum Essay

In May, the 194 member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) will decide whether to adopt two international instruments with the potential to transform how the world prepares for and responds to pandemic threats: reforms of the International Health Regulations (IHR) and a new pandemic treaty (dubbed the pandemic agreement). Each draft instrument contains bold new commitments for disease surveillance, capacity building, and more equitable access to health products, and we discussed the strengths, limitations, and ethical foundations of these proposals recently in the Hastings Center Report. But none of these reforms can be achieved without ample and sustainable funding.

Financing takes two broad forms: shoring up WHO’s financial base allowing it to implement a global health agenda unfettered by the demands of a small set of donors and funding to underwrite low- and middle-income countries’ activities under the new instruments. In this essay, we discuss these major reforms and then explore the significant challenges and opportunities for financing them.

This year will be the most important moment for global health since WHO’s founding in 1948, but only if states give major reforms their full political and financial backing.

The Pandemic Agreement

In response to Covid’s profound preparedness and response shortcomings, 25 heads of state and international agencies issued an extraordinary joint call for a new pandemic agreement that would have the force of international law. The World Health Assembly (WHA) established an intergovernmental negotiating body to draft and negotiate the agreement, with core obligations that could make the world healthier and safer, and with equity as its north star.

One Health. The One Health approach is sometimes called deep prevention because it addresses the major drivers of disease outbreaks, including anthropogenic, ecological, and environmental risks. Most infectious diseases have zoonotic origins, whereby animal infections spill over to humans. Climate change, deforestation, intensive animal farming, and trade in wild animals bring animals and humans into closer proximity, sparking spillovers. The draft text of the pandemic agreement released this month creates norms for a range of One Health commitments, but actual obligations to develop financial and technical support mechanisms needed to fulfill these commitments take effect only “as appropriate”–language that serves as a legal escape hatch. Resource-constrained nations accordingly feel they are being cajoled into these responsibilities with few assurances that funding to underwrite them will follow. The failure from governments to provide even modest resources may miss an opportunity morally and financially, as pandemic prevention would cost just a fraction of that of a full-scale pandemic–by one account representing less than 1/20th of the value of lives lost to emerging pathogens.

Equitable access to countermeasures. Inequitable access to life-saving vaccines and other countermeasures became one of the major themes of the Covid crisis. The WHO-led COVAX facility was formed to facilitate vaccine equity, but COVAX’s work was thwarted by high-income countries, which gobbled up early vaccine supply resulting in scarcity and unaffordable prices to others. By the end of 2021, vaccination coverage was close to 75% across high-income countries compared to less than 2% in many low-income countries, falling well short of COVAX’s 20% coverage target. This cannot possibly be an acceptable outcome.

The draft agreement attempts to remediate this disparity in future pandemics by incorporating obligations to build national, regional, and international clinical trial and research and development capacities in low- and middle-income countries and promote open scientific exchange. The draft also calls on countries to include terms in publicly funded research and development agreements that effectively condition the provision of public money on manufacturer commitments that enhance equity during health emergencies, such as on licensing, affordable pricing, technology transfer on voluntary terms, and adherence to WHO product allocation frameworks. The draft would establish a WHO-run global supply chain and logistics network to avoid competition for vital resources and attempts to promote the transfer of technology and know-how. The African bloc, however, has slammed the use of waffling language that eschews any attempt to hold high-income countries to account for failing to fulfill their obligations to ensure equity. Others bemoan the potential disruption these reforms could make to the research and development ecosystem that already disincentivizes investment in vaccines.

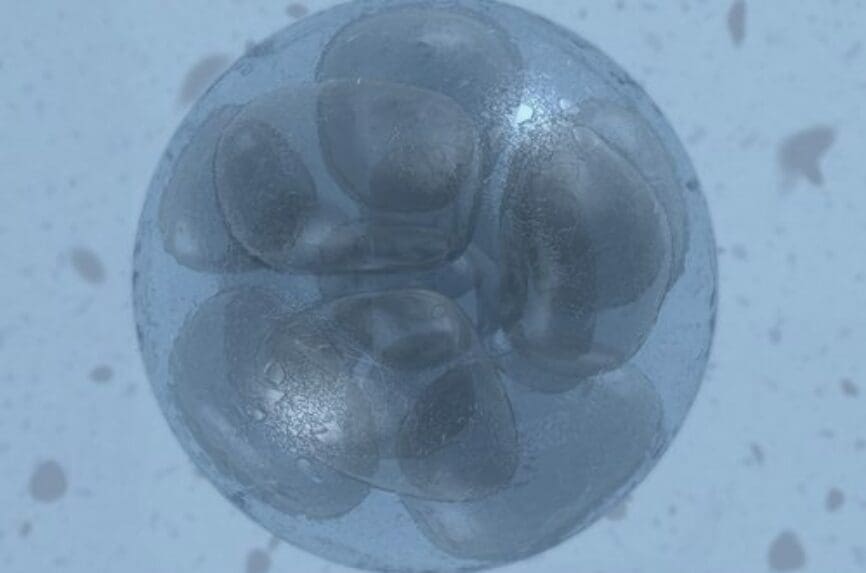

As we write, the make-or-break issue is the construction of a workable system of pathogen access and benefit sharing (PABS), drawing inspiration from the WHO’s Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework, pursuant to which countries would share pathogen samples and associated genetic sequence data discovered within their borders with a network of WHO-coordinated laboratories. Manufacturers that create viable countermeasures using PABS samples or data would then provide 20% (10% free of charge and 10% at reduced prices) of their real-time production through WHO’s global supply chain network for distribution based on public health risk and need. Manufacturers would also annually contribute funding for the PABS system and make voluntary nonmonetary contributions to support it, including guarantees on tiered pricing, scientific collaboration, capacity-building, and arrangements for the transfer of technology and know-how.

Proponents hope that codifying legal obligations on PABS would support global health security and justice. However, the draft is silent on how manufacturers, universities, and other private users–who are not traditionally considered actors under international law subject to treaty obligations–will be persuaded to use the system or whether ratifying nations will use their domestic lawmaking power to require it. Manufacturers might also elect not to create low return-on-investment products such as vaccines, so a workable PABS has to contemplate how to keep them engaged. Nonetheless, establishing a strong PABS system through the agreement is vital, as 290 scientists recently warned that without it vaccine inequity will be almost guaranteed in the next pandemic.

Accountability. No agreement can be effective without ways to hold parties to account for the commitments they make. International law, operating independently of other inducements, is notoriously weak as a mechanism to change behavior when up against national self-interest during a global crisis. Unsurprisingly, negotiators have had a hard time innovating new compliance levers. The draft agreement would establish a conference of the parties (COP) to periodically review treaty implementation and mobilize funding, but it contains no independent monitoring or oversight. It ought to have an independent committee or other mechanism to monitor states’ compliance and reporting, and a separate peer review mechanism, both of which could report to an empowered COP with civil society and stakeholder engagement and the power to publish reports. It could connect the treaty to existing global monitoring and evaluation frameworks, and should introduce a system of incentives for compliance and distinctives for noncompliance. If the pandemic agreement is to live up to its stated objectives and give the world a fighting chance when the next pandemic threat emerges, the COP will need to develop the incentive structure that makes fulfilling treaty commitments more enticing than the alternative.

The International Health Regulations

A working group of WHO member states has simultaneously been negotiating amendments to the IHR, a legally binding agreement among 196 IHR states parties designed to detect, assess, and report emerging pathogenic threats. Led by the U.S., governments proposed over 300 amendments–indicating a near-universal desire to improve the regulations which were last significantly reformed after the SARS-CoV-1 pandemic of 2002-2004. While IHR reform has had less public attention than the pandemic agreement, the regulations have a clear advantage: they are already in place, and amendments come into force automatically for all WHO members unless they explicitly opt out.

Core capacities. The IHR requires states parties to develop, strengthen, and maintain capacities to detect, assess, notify, report, and respond to public health risks. Weak health systems thwart pandemic responses, but while the IHR obliges member states to assist and cooperate “to the extent possible,” there has been precious little technical and financial assistance.

Equity. The IHR is currently silent on equity, so proposals related to equity have been at the heart of the negotiations. Operative proposals include a new article on access to health products, technologies, and know-how that would give the WHO Director-General the power to make recommendations to promote timely availability and affordability of countermeasures to respond to a public health emergency of international concern. Some IHR negotiators from high-income countries have attempted to consolidate equity measures under the pandemic agreement, though the implications are unclear.

Accountability. Accountability mechanisms are virtually nonexistent in the IHR, save for a never-used dispute settlement mechanism. The U.S. and the African bloc have proposed “compliance” or “implementation” committees, whose function would be to boost IHR adherence thus adding a welcome layer of accountability. There are financial costs, however, and without an identifiable capital source, this could result in an unfunded mandate.

As we’ve previously discussed, in 2022 WHO member states made an important decision to shore up the agency’s financing, putting it on a path to greater flexibility and capacity to fulfill its mandate as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work. WHO historically relied on voluntary and usually earmarked contributions from a small set of wealthy government and private donors. This limited WHO’s ability to fulfill its triple billion targets for universal health coverage and health emergency protections, address neglected areas of global health like injuries and noncommunicable disease, and otherwise keep the ship afloat through talent acquisition, retention, and pay.

The 2022 decision included phased increases to member states’ assessed (i.e. mandatory, unrestricted) contributions to a total amount equal to 50% of the approved 2022 base budget by 2030 on a defined stepwise scale. The following year, WHO member states agreed to the first step: to raise their assessed contributions to 26% of WHO’s 2022-2023 base budget. This year, the agency is also seeking to raise an additional $7.1 billion in voluntary contributions in a replenishment conference based upon a compelling investment case to secure a stable workforce, reduce major gaps in health policy, and assume a central role in international health work. WHO smartly constructed and announced what it planned to do with these contributions upfront rather than requesting a blank check. It is also important that WHO’s member states lead the way, as private donors will want to see that WHO’s membership is fully committed. We proposed five strategies for WHO to stay on track with this fundraising and continue to maintain they are critical to the agency’s future.

Opportunities and Barriers to Sustainable and Adequate Financing

Adam Smith’s lament that “no complaint . . . is more common than that of a scarcity of money” is pertinent to this discussion. There is much to improve concerning pandemic readiness, but the already inadequate funding that was mobilized early in the decade is drying up while much of the public expresses an understandable desire to put the Covid crisis behind it. The problem is that viruses and other infectious agents do not particularly care. We can invest now in prevention or be compelled to spend orders of magnitude more later to cope with a pernicious threat that will cost lives and livelihoods.

The headwinds for financing new activities under the IHR and pandemic agreement are substantial. Global health financing is heavily fragmented and new mechanisms risk splintering already limited capital even more. The current cafeteria of choices includes U.N. agencies, funds, and programs (e.g., WHO, UNICEF, UNDP, UNAIDS), hosted trust funds (such as those within the development banks), and global public-private partnerships (Global Fund, GAIN, Gavi). Relatedly, capital is also required to fund universal health coverage, biomedical research, regulatory oversight, and public awareness campaigns. While there is some coordination among key actors (for example, WHO and UNICEF partner and coordinate with Gavi), they are also competitors for a limited global health till.

Moreover, the competition for donor government finance is incredibly intense, with climate change, humanitarian assistance, national security, and other priorities pining for funding. On top of all this is a growing nationalist populism, which is dead set against international institutions as a mode for solving common interest problems.

Public spending on pandemic measures is facing downward pressure and segments of the public have voiced displeasure on how previously appropriated funds were spent. Private finance tends to pursue return on investment, and the markets most in need of improved pandemic assistance are often the riskiest in which to invest. The strategies to generate capital to fund new obligations in the IHR and pandemic agreement must cope with the realities of fragmentation and competition, factors that have likely contributed to the resounding undercapitalization in the World Bank’s Pandemic Fund.

There was considerable anxiety in some quarters that amending the existing IHR while negotiating a new pandemic agreement would itself fragment efforts, and so the IHR and international negotiating body groups have coordinated some, but not all, of their discussions. Notably, on January 31, the two negotiating bodies met to discuss, among other things, “financing and key areas of overlap [because] a coordinated approach is needed to continue to ensure these important issues are properly reflected across the two processes.” They met again on February 23 to debate whether to consolidate financial mechanisms within the pandemic agreement. Assuming both instruments are adopted in May, the WHO should facilitate coordination between the mechanisms to prevent undue fragmentation and to maximize value for money.

Financing the Pandemic Agreement

A primary reason that many states have failed to build IHR health capacities is a lack of resources to do so. To address this problem, the draft text of the pandemic agreement calls on state parties to “prioritize . . . domestic funding;” “mobilize financial resources through all sources, including existing and new bilateral, subregional, regional and multilateral funding mechanisms” including through grants and concessional [i.e. sub-market rate] loans; promote “debt relief, including suspension of debt servicing and debt cancellation;” and “encourage governance and operating models of existing financing entities to minimize the burden on countries.” The March 2024 draft introduces obligations for states to cooperate by promoting financial assistance to lower-income countries for capacity-strengthening, but, like the IHR, provides no real obligation, detail, or benchmarking for that cooperation. It also requires the agreement’s governing body to “adopt, every five years a Financial and Implementation Strategy” and the parties to align with the strategy “while financing the relevant funding mechanisms, both within and outside WHO.”

What may capture the most interest is a new “Coordinating Financial Mechanism” to support implementation of both instruments and will consist of a “pooled fund to provide financing to support, strengthen and expand capacities” and “promote harmonization and coordination for financing” for pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response. It would also provide financing for day zero surge response “as necessary.” The mechanism will be accountable to the COP, which “shall periodically review [its] effectiveness.”

The funds would come from monetary contributions through the PABS system (if adopted and implemented) and voluntary contributions from state and nonstate actors, but the draft leaves additional sources of financing for the COP to determine.

The mechanism’s mandate to coordinate financing may be the most useful element, recognizing the fragmented state of global health financing. WHO is the only institution credibly positioned and constitutionally mandated to act as the directing and coordinating authority on international health work. By examining the sources of funding available for pandemic, prevention, preparedness, and response, it can provide the big picture of the state of financing.

The quintennial financial strategy review is prudent and appropriate. To make progress, the treaty’s governing body and secretariat will need to make reasonably reliable financial forecasts and identify needed funding for urgent activities. A five-year horizon is likely the longest possible to achieve specific targets; anything longer and countries and other actors may water down specific metrics into the aspirational language that international agreements are often criticized for employing. Moreover, pandemic priorities will change and so periodic opportunities to adjust them are practical.

To be effective, the pooled fund would need to be reliable and its revenue predictable and sustainable. As outlined, however, it risks creating another hand grasping at limited capital and a potentially visible point of failure and criticism. It is not clear why its funding targets will be met when so many others for global health have not. That it will rely heavily on a hotly debated PABS system for capital will make it more difficult to be viewed as a reliable purchaser or counterparty that could access favorable pricing for products or services.

Higher-income countries appear unwilling to commit to tangible financing through the main text of either instrument. Understandably, low- and middle-income countries demonstrate skepticism to agreeing to tangible commitments with assured funding elusive. It is hard to imagine that the pooled fund would be sufficiently capitalized or reliable to be the impetus for a breakthrough.

New Financing Mechanisms for the IHR

IHR financial negotiations have not significantly progressed. Yet, several proposals would expand the types of financial assistance available, including a new mechanism to support developing countries in strengthening core capacities and health systems, building research and development capacities, and addressing health inequities. As noted above, creating another mechanism is risky. If the negotiators elect to do it, WHO should coordinate it with an eye toward preventing fragmentation or reallocation from other critical health aims or its own core budget.

A Future Worth Investing In

Negotiators are now rapidly hurtling toward May’s formal adoption target while WHO continues to make its case to stakeholders. There is palpable urgency; the next pandemic may be waiting in the wings and right now humanity is woefully unprepared. A failure to meet the moment with strong commitments and mechanisms for adequate and sustainable financing would leave us on the back foot and would repeat Covid’s complicated and ethical challenges. Refusal of countries to commit the finances commensurate with their resources and capabilities would create extraordinary burdens on the most vulnerable and ultimately make responding to the next pandemic more expansive for all of us.

Kevin A. Klock, JD, is senior vice president, chief operating officer, and general counsel at the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health, a scholar at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, and an adjunct professor at Georgetown University Law Center. @KlockStndTime

Alexandra Finch, LLB, LLM, is an associate at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law and an adjunct professor of Law at Georgetown University Law Center. @avgfinch

Lawrence O. Gostin, JD, LLD (Hon), is the founding O’Neill chair in Global Health Law and co-faculty director at the O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law, Distinguished University Professor at Georgetown University, and director of the WHO Collaborating Center on Global Health Law. He is a Hastings Center fellow. @LawrenceGostin

DISCLAIMER:

Professors Gostin and Klock lead the O’Neill Institute and Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) project on an international instrument for pandemic prevention and preparedness. The FNIH provided funding to the O’Neill Institute for the project. Professor Gostin is the director of the WHO Collaborating Center on National and Global Health Law. Gostin is also a member of WHO’s IHR Review Committee. WHO is an intellectual non-financial partner to the FNIH-managed GeneConvene Global Collaborative. The views in this piece are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the FNIH or O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law.