Bioethics Forum Essay

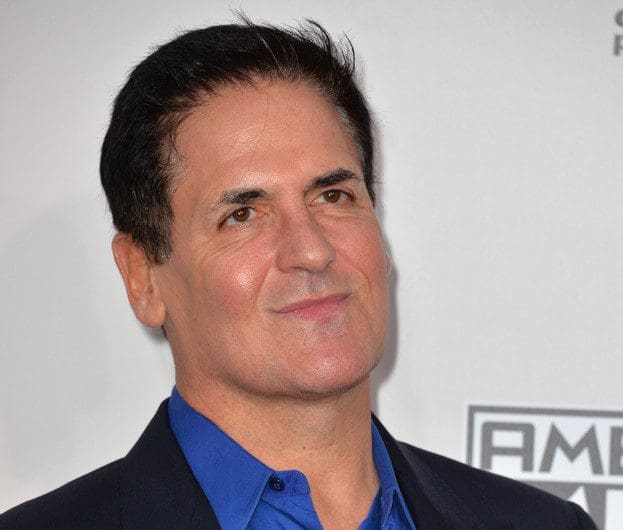

Mark Cuban’s Innovative Pharmacy: A Band-Aid on Drug Prices

Billionaire Mark Cuban and physician Alex Oshmyansky recently launched the innovative Mark Cuban Cost Plus Drug Company (MCCPDC), an online pharmacy that sells generic prescription medicines at significantly lower prices than other sources. For example, a 30-count of imatinib, a cancer drug that typically costs over $2,000, is $17.10 at MCCPDC. A recent Annals of Internal Medicine article found that Medicare could have saved up to $3.3 billion by purchasing generics from MCCPDC. The pharmacy currently offers more than 800 generic drugs, and its inventory is growing. The company plans to open its own manufacturing site next month.

The pharmacy has been called a “game changer” that could “change millions of lives in this country.” At a time of surging drug prices, Cuban has raised hope that this initiative could disrupt the landscape of prescription medicine in the United States. But the unnuanced acclaim for the pharmacy may eclipse attention to the longstanding structural problems of the pharmaceutical industry and MCCPDC’s role in it. Without discounting its advantages, it is imperative to examine MCCPDC critically, given how it is situated within the ethical landscape of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry.

Prescription drugs in the U.S. cost two and a half times more than in other Western countries, with prices increasing faster than the inflation rate. In a poll last year, 7% of U.S. adults, representing about 18 million people, reported that they were unable to pay for at least one prescription medication for their household during the prior three months, and 10% said that they had skipped doses. These hardships disproportionately affect low-income households and those with chronic diseases.

Despite the difficulties people face in affording their medications, pharmaceutical companies make massive profits. Patents typically last for about 20 years; however, many pharmaceutical companies manage to extend patent protection for longer periods, delaying the production of more affordable generic versions. But even generic medications are subject to markups as high as 10,000 times the manufacturing cost. On average, only $17 of every $100 spent at retail pharmacies goes to direct production costs; the remainder is split between drug companies and intermediaries in the pharmaceutical supply chain known as pharmacy benefit managers. Pharmacy benefit managers negotiate payment rates with drug manufacturers on behalf of insurance plans through a system that encourages drug companies to raise prices in order to compete with one another.

This is where MCCPDC comes in. It eliminates the intermediaries and charges customers for the cost of ingredients and manufacturing, plus a 15% margin, a $3 pharmacy dispensing fee, and a $5 shipping fee, leading to drastically lower prices. Cuban’s pharmacy promotes transparency by operating outside of the insurance system and sidestepping the pharmaceutical supply chain’s intermediaries, whose opaque negotiations with manufacturers, pharmacies, and health plans lead to inflated drug prices. “What we’re doing is a win-win-win,” Cuban has stated. “We decrease the administrative burden so pharma has more money for research and development, people save capital, patients get the drugs, and the health system saves on the whole.”

This initiative, created by a champion of the free market, exposes the obscene problems associated with our health care system, which exploits the need for health care as an opportunity for profit rather than recognizing health care as a human right. Many scholars argue that health care is indeed a human right because it is necessary for enabling equal opportunity regardless of factors such as race, class, and gender. If we recognize that health care should be available to all as a matter of justice, collective efforts towards promoting changes in social policy and providing social safety nets would be the principal ways to ensure a system that benefits all, not just some.

MCCPDC will undoubtedly help many who struggle to afford generic medications, yet the pharmacy has major drawbacks that limit who will benefit and to what extent. First, it does not currently offer patented, brand-name drugs, which cause the largest financial burdens for patients – generics accounted for less than 11% of prescription drug spending in 2020. Second, the pharmacy does not accept insurance. This may not be an issue for patients with high deductibles or copays, but those who make frequent pharmacy visits and/or have low deductibles may have lower out-of-pocket costs with traditional pharmacies.

The impact of MCCPDC is also limited on a systemic level. Traditional retail pharmacies must navigate the system of intermediaries in order to provide life-saving drugs that are still patented and to accept insurance. Forbes notes that, in contrast to MCCPDC, these pharmacies “would lose practically all their business … if [they] were to turn down all of the insurance plans that they manage and become cash-only.” By sidestepping the systemic issues faced by other pharmacies, MCCPDC’s model is an exception within a system that other pharmacies must continue to navigate.

Beyond these limitations, MCCPDC’s very existence is an affirmation of the unchecked capitalist model of the pharmaceutical industry, not a challenge to its social and legal foundations. MCCPDC’s model is a function of Cuban’s extreme wealth; Cuban recently admitted that “it wouldn’t be possible to do what he was doing unless he didn’t need to make money.” Furthermore, as a public benefit corporation, Cuban’s pharmacy has the stated goal of making “a profit while maximizing impact.” The paradox in this scenario is that the vast wealth that allows MCCPDC to exist is made possible by the same socioeconomic systems in the U.S. that drive the social and health inequities it aims to fix. More specifically, policies that allow for the mass accumulation of wealth also perpetuate poverty and erode funding for public programs and social services. Therefore, good-faith efforts from wealthy people to fix inequities caused by wealth distribution are largely insufficient.

Many scholars argue that when we rely on the beneficence of the wealthy to address disparities, we release the government from its responsibility to correct harmful structures. Paul Gomberg, for example, argues that the focus on immediate relief in philanthropy tends to obscure the systems that create and exacerbate inequalities in the first place. To realize health as a human right, the bottom line of public-benefit efforts must be the creation of sustainable health care models. While Cuban’s public benefit corporation is a step in the right direction, the initiative can at most provide a Band-Aid solution–one that replicates existing programs, such as GoodRx’s and Walmart’s, for low-cost generic medications.

This reliance on the wealthy elite begs the question: What if Mark Cuban and other billionaires donated their funds to support the creation of a sustainable social program for equitable access to prescription medications? While such social programs remain out of reach, MCCPDC could, in the meantime, increase its impact by pursuing a more holistic model–for example, by providing low-cost drug options and supporting advocacy efforts for policy change. The efforts of billionaires like Cuban to push senators for drug pricing reform legislation, a version of which just passed in the Senate, would not go unnoticed. Such a dual mission would prioritize the structural issues while continuing to fill a gap in current resources, thereby addressing both long-term and short-term needs.

MCCPDC offers a technocratic stopgap in the face of massive systemic issues, but we ultimately need changes in social policy to ensure that structural failures do not continue to perpetuate health inequities. As stated by philosopher Lisa Herzog, “if we take social structures as a given … [the only option] is to spend some of our spare money to help repair the worst damages that this system does.” The examples provided by pharmaceutical systems in many other countries show us that fair drug pricing is achievable through approaches such as centralized price negotiations, universal health coverage, and restrictions on out-of-pocket spending through insurance plans. Because Cuban’s pharmacy is situated within a system that is failing to provide equal access to health care, the initiative is only able to provide a short-term solution for a problem that will persist and worsen as we continue to permit the prioritization of profit over human rights.

Aashna Lal and Margaret Matthews are project manager-research assistants at The Hastings Center. Danielle Pacia (@DaniellePacia) is a senior project manager-research assistant at The Hastings Center.

I love that Mark Cuban has tried to kelp those of us who can’t afford. I have a movement i I I I have a disorder that makes me fall. I have been given the medication Austedo that I OK cannot afford