Bioethics Forum Essay

Responding to Ebola: Organizational Ethics, Frontline Perspectives

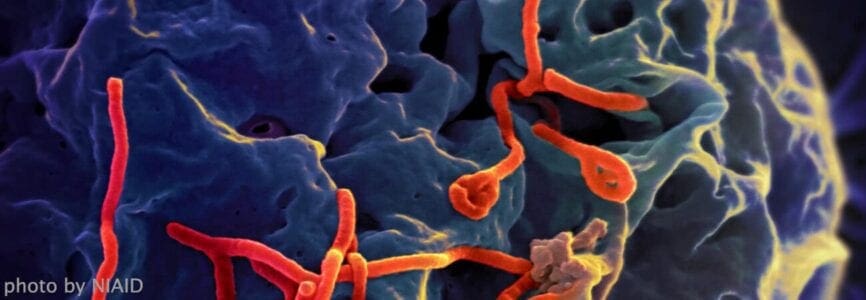

Beyond crucial questions of fair access to scarce supplies of the experimental drug ZMapp and to other potentially effective drugs to treat Ebola, commentators from bioethics, public health, journalism, and other sectors are increasingly focused on “staff, stuff, and systems.” The consequences of chronically inadequate local and national public health infrastructures in developing countries are tragically revealed as systems in affected West African nations are overwhelmed by epidemic. In a recent interview Hastings Center Fellow George Annas described the Ebola epidemic as a “public health disaster that requires a heavy-duty public response,” including capital investments in clinics in addition to emergency measures needed to control the spread of the highly contagious virus, and to care for the sick. Annas also cautioned against reducing ethical questions to procedures for drug testing and allocation, important as these issues are.

Funding cutbacks and the loss of expert staff through attrition at global entities such as the World Health Organization (W.H.O.) are also problems with ethical dimensions, as uncertainty over who should be responsible for coordinating an effective response to the epidemic persists. Margaret Chan, director general of the W.H.O., told NPR that her financially strapped organization should play a primarily supportive role, a position characterized as unconvincing in a September 6 New York Times editorial. Commentators widely acknowledge severe, seemingly insoluble shortages of health care workers, plus supply-chain breakdowns, as air and sea deliveries of supplies and the movement of supplies on the ground are interrupted due to fear of transmission during unloading, and to roadblocks. The Timeseditorial concludes by suggesting that the United States may need to step in to coordinate the international response if the U.N. and the W.H.O cannot.

The crisis is producing a range of striking first-person narratives.

In a “Perspective” in the New England Journal of Medicine, “A Good Death – Ebola and Sacrifice,” Josh Mugele, an emergency medicine physician, and Chad Priest, a nursing school dean, at Indiana University wrote about working with staff at JFK Memorial Medical Center in Monrovia, Liberia on a disaster-medicine project in 2013. They became friends with Sam Brisbane, whom they described as “a genuine ED doc – at once caring and profane, light-hearted one minute, intense the next.” Brisbane confided that of all the potential disasters that might hit his institution, an Ebola-type epidemic “scared him the most” because of barriers to basic infection control – not enough gloves, not enough soap, not enough adherence to universal precautions.

Mugele and Priest were in Monrovia in June of this year, as the first cases of Ebola appeared in the city, and at JFK. After their return to the U.S., they learned that Brisbane was ill, then dead. During the summer, they learned of the deaths of other Liberian colleagues. Mugele and Priest struggle with the true ethical dilemma faced by their friend Sam Brisbane – the duty of care, of nonabandonment of patients – versus the “duty to ourselves and our families” when faced with working conditions in which professionals lack the protective gear and other resources needed to protect themselves from infection. They conclude that Brisbane died a “good death,” in choosing to show up for work despite the terrible risk, and also that he died “horribly and unjustly.”

In an essay in the New York Times, Pardis Sabeti, a geneticist affiliated with Harvard and the Broad Institute who has collaborated with African colleagues to sequence and monitor the genomes of hemorrhagic viruses, describes the experiences of Sheik Khan and other investigators in Sierra Leone who were also frontline clinicians in hospitals overwhelmed with Ebola cases. Noting that Khan’s institution, Kenema Government Hospital, had sophisticated diagnostic and contact-tracing capacities but others did not, Sabeti writes:

If diagnostic facilities like those at Kenema had been more widely available, the virus could have been caught as it emerged. A team of trained individuals, perhaps 50 people, could have been sent to the site of the outbreak before it spread, and stayed for 50 days after the last infection. Working with the local community, they could have isolated and treated the sick, buried the dead, traced each person’s contacts over the incubation period, performed outreach and education services, and ensured food supplies, all while keeping themselves safe from infection. With the virus confined to one village, this large-scale 50-50 approach would have been a modest investment for the world.

Instead, the virus was allowed to escape the first village, and then to spread into four more countries. That missed opportunity has cost the lives of many people, including my good friends. . . . Dr. Khan would have spent this summer with me at Harvard and the Broad Institute, training in advanced molecular diagnostics for genomic surveillance. Instead, Dr. Khan is gone.

Chelsea Jack is a research assistant at The Hastings Center and a 2014 graduate of the University of Virginia. Nancy Berlinger is a Hastings Center research scholar who directed a project on pandemic planning.

Posted by Susan Gilbert at 09/09/2014 03:24:12 PM |